| Issue |

A&A

Volume 706, February 2026

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A296 | |

| Number of page(s) | 27 | |

| Section | Stellar structure and evolution | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202555500 | |

| Published online | 18 February 2026 | |

Comfort zones of stars: A limit on orbital tightening via stable mass transfer shapes the properties of binary black hole mergers

1

Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics Karl-Schwarzschild-Strasse 1 85748 Garching, Germany

2

European Southern Observatory Karl-Schwarzschild-Strasse 2 85748 Garching bei München, Germany

3

London Centre for Stellar Astrophysics Vauxhall London, UK

4

University of Oxford St Edmund Hall Oxford OX1 4AR, UK

5

Argelander Institut für Astronomie Auf dem Hügel 71 53121 Bonn, Germany

6

Max-Planck-Institut für Radioastronomie Auf dem Hügel 69 53121 Bonn, Germany

★ Corresponding author: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

13

May

2025

Accepted:

26

September

2025

Mass transfer in binary systems is the key process in the formation of various classes of objects, including merging binary black holes (BBHs) and neutron stars. The orbital evolution that occurs during mass transfer depends on how much mass is accreted and how much angular momentum is lost – two of the main uncertainties in binary evolution. This poses a challenge for obtaining reliable predictions from binary channels. Here, we demonstrate that despite these unknowns, a fundamental limit exists to how close binary systems can become via stable mass transfer (SMT) that is robust against uncertainties in orbital evolution. Based on detailed evolutionary models of interacting systems with a BH accretor and a massive-star companion, we show that the post-interaction orbit is always wider than ∼10 R⊙, even when extreme shrinkage due to L2 outflows is assumed. Systems evolving toward tighter orbits become dynamically unstable and result in stellar mergers. This separation limit has direct implications for the properties of BBH mergers, including long delay times (≳1 Gyr) and an absence of high BH spins from the tidal spin-up of helium stars. At high metallicity, the SMT channel may be severely quenched due to Wolf-Rayet winds. We predict BBH mergers from ∼10 M⊙ to 90 M⊙, with case A mass transfer dominating above 40 M⊙. The reason for the separation limit lies in the stellar structure, not in binary physics. If the orbit becomes too narrow during mass transfer, a dynamical instability is triggered by a rapid expansion of the remaining donor envelope due to its near-flat entropy profile. The closest separations can be achieved from core-He burning (∼8−15 R⊙) and Main Sequence donors (∼15−30 R⊙), while Hertzsprung gap donors lead to wider orbits (≳30−50 R⊙) and non-merging BBHs. These outcomes and mass transfer stability are determined by the entropy structures, which are governed by internal composition profiles. Consequently, the formation of BBH mergers and other compact binaries via SMT is a sensitive probe of chemical mixing in stars, and it may help address open questions of stellar astrophysics, such as the blue supergiant problem. Finally, we propose a new simplified treatment of mass transfer stability that more accurately reproduces detailed results and remains flexible under varying assumptions for orbital evolution.

Key words: gravitational waves / binaries: general / stars: black holes / stars: evolution / stars: interiors / stars: massive

© The Authors 2026

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model.

Open access funding provided by Max Planck Society.

1. Introduction

We are at the brink of the data-driven era of gravitational-wave (GW) astrophysics. With the three observing runs concluded and the fourth run O4 currently underway, the LIGO-Virgo-Kagra collaboration has reported detections of about 100 compact binary coalescences, most of which are binary black hole (BBH) mergers (Abbott et al. 2021, 2023). In the next few years, the number of GW detections will increase to thousands and eventually many millions with the increasing sensitivity of the current detectors (O4-O5, AdV+ Abbott et al. 2020) and the next-generation instruments, such as the Einstein Telescope (Maggiore et al. 2020) and Cosmic Explorer (Reitze et al. 2019). With millions of compact binary coalescences detected every year, merging pairs of black holes (BH) and neutron stars (NSs) will arguably become the best measured state in the evolution of massive stars across the Universe.

Gravitational-wave astronomy has an enormous potential for probing massive-star formation and evolution across all environments and redshifts. The key to unlocking this treasure chest are population models exploring formation scenarios for GW sources that allow for a confrontation between theory and observation. However, this undertaking is currently hindered by the “Interpretation Challenge”: due to severe uncertainties and multiple free parameters in the formation scenarios, we are unable to robustly interpret the observed population and link the GW sources with their progenitor stars (Broekgaarden et al. 2022a; Mandel & Broekgaarden 2022; Chruślińska 2024). The task is not made easier by the fact that multiple diverse formation channels may simultaneously be at play (Zevin et al. 2021), such as isolated evolution of stellar multiples (Belczynski et al. 2016; Tauris et al. 2017; Stevenson et al. 2017; Antonini et al. 2017; Kruckow et al. 2018; Mapelli & Giacobbo 2018; Belczynski et al. 2020; Vynatheya & Hamers 2022), dynamical evolution in dense stellar clusters (Rodriguez et al. 2016; Askar et al. 2017; Samsing 2018; Rodriguez et al. 2019; Mapelli et al. 2021, 2022), evolution in gas-rich environments such as active galactic nucleus disks (Antonini & Rasio 2016; Stone et al. 2017; McKernan et al. 2018; Samsing et al. 2022), or channels involving the existence of primordial BHs formed shortly after the Big Bang (Sasaki et al. 2018; Papanikolaou et al. 2021).

|

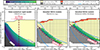

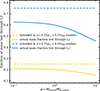

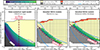

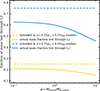

Fig. 1. Schematic comparison of orbital shrinkage via common envelope and stable mass transfer in a BBH merger progenitor (here a binary with a 35 M⊙ stellar donor and 10 M⊙ BH accretor), based on a simple analytical model (Sect. 2.3) rather than a detailed evolutionary calculation. The SMT lines follow assumptions typically used in population synthesis of GW sources, naively suggesting that mass transfer with enhanced AM loss (blue) can produce separation as small as CE evolution. In this paper, we use detailed binary evolution calculations to show why this is not the case (Fig. 3). |

All the formation scenarios necessarily need a way to bring two BHs or NSs close together such that they spiral inward due to GW emission and merge within the age of the Universe. In isolated binaries, with the exception of chemically homogeneous evolution (Mandel & de Mink 2016; de Mink & Mandel 2016; Marchant et al. 2016; Riley et al. 2021), this is achieved through mass transfer interactions between the binary components. Classically, the key stage in the binary channel has been a phase of dynamically unstable mass transfer, leading to common envelope (CE) inspiral (Tutukov & Yungelson 1993; van den Heuvel 1994; Tauris & van den Heuvel 2006). This view emerged quite naturally. The dramatic shrinkage of the orbit during a CE phase is thought to produce a very short period binary (Ivanova et al. 2013, 2020) that comfortably falls into the separation range required for GW-induced mergers (Fig. 1). In comparison, stable mass transfer (SMT) evolution can lead to all sorts of different outcomes, from moderate orbital shrinkage to orbital expansion and wide post-interaction systems (Tauris & van den Heuvel 2023, and references therein).

In recent years, the CE-focused picture has been undergoing a revision, driven by the emergence of systematic studies with detailed stellar and binary evolutionary models dedicated to the formation of GW sources (Mennekens & Vanbeveren 2014; Kruckow et al. 2016; Eldridge & Stanway 2016; Fragos et al. 2019; Klencki et al. 2020, 2021; Marchant et al. 2021; García et al. 2021). The argument is that the survival of a CE event from a massive BH progenitor may be a much rarer and fine-tuned event than previously thought, putting in question the efficiency of the CE channel for the formation of massive BBH mergers. At the same time, it has been pointed out that even though the orbital shrinkage from SMT evolution is not as substantial as during a CE phace, it can also produce sufficiently short-period orbits for BBH mergers if the interaction begins in a relatively narrow orbit to begin with (see Fig. 1 van den Heuvel et al. 2017; Neijssel et al. 2019; Marchant et al. 2021; Gallegos-Garcia et al. 2021; Picco et al. 2024). This realization came in part following arguments that mass transfer stability increases with the stellar mass (Ge et al. 2015, 2020; Pavlovskii et al. 2017; Olejak et al. 2021). The SMT channel for BBH mergers was established, with the SMT phase in question taking place after the first BH has already been formed, at the BH+Star binary stage.

A key question for any formation scenario is what are the orbital separations or periods of the double compact objects (DCOs) it predicts. This is because the size of the orbit is the primary factor determining the time it takes for a DCO to merge (tmerge ∝ a4), and it dictates whether GW sources preferably trace star-forming galaxies (tmerge ≲ 100 Myr) or whether they are remnants of massive stars formed in high-redshift environments (tmerge ≳ 1 − 10 Gyr; Chruslinska et al. 2019; Chruslinska & Nelemans 2019; van Son et al. 2022a). The orbital separation at the BH–Wolf-Rayet stage (i.e., just prior to the formation of the second BH) has a strong effect on the tidal torque (∝a−6 Zahn 2008) and therefore the amount of angular momentum (AM) in the Wolf-Rayet star at core-collapse (Ma & Fuller 2023). This directly affects the amount of AM in the BH progenitor at the point of core-collapse, which likely determines the BH spin. Tidally locked BH–Wolf-Rayet systems with orbital periods as short as ≲0.5 − 1 day may be required to explain the observed non-zero effective spins of BBH mergers as products of binary evolution (Detmers et al. 2008; Kushnir et al. 2016; Zaldarriaga et al. 2018; Belczynski et al. 2020; Bavera et al. 2020, 2021; Ma & Fuller 2023).

Despite their importance, the orbital separations of massive DCO systems are difficult to predict in binary channels. In the case of CE evolution, 3D hydrodynamic simulations cannot yet resolve the innermost region of the envelope and model the final stages of the inspiral to find the resulting orbit (e.g., Moreno et al. 2022, although see Law-Smith et al. 2020). Following CE ejection, the orbit may further be altered due to an interaction with the substantial amount of circumbinary material that has not become fully unbound (possibly of a disk-like structure Wei et al. 2023; Gagnier & Pejcha 2023) or an additional mass-transfer phase (Vigna-Gómez et al. 2022; Hirai & Mandel 2022). With no unambiguous massive post-CE systems discovered to date (Kruckow et al. 2021), there are few observational constraints to guide the models. Most GW-source population models predict post-CE separations according to the energy budget criteria (van den Heuvel 1976; Webbink 1984; Livio & Soker 1988), with no lower limit other than the crude requirement that the naked He core must fit into its Roche lobe in the post-CE orbit.

In the case of SMT evolution, the main source of uncertainty for orbital shrinkage is the assumption of how much orbital AM is lost with the non-accreted matter (the more AM that is lost, the more the separation decreases). The key mass transfer phase takes place at a high-mass X-ray binary stage. The mass transfer rates are typically highly super-Eddington (King & Ritter 1999; Podsiadlowski & Rappaport 2000; Podsiadlowski et al. 2002), leading to supercritical accretion disks and, depending on the viewing angle, the appearance of an ultraluminous X-ray source (ULX; Shakura & Sunyaev 1973; King et al. 2000; Poutanen et al. 2007; Lasota et al. 2016). Most of the transferred mass likely never reaches the BH but is instead ejected from the disk in the form of jets and bipolar outflows or disk winds or as a slow ejecta concentrated in the equatorial plane (Lipunova 1999; McKinney et al. 2014; Sądowski et al. 2014; Sądowski & Narayan 2015; Sądowski & Narayan 2016). All of those components have been observed in the Galactic X-ray system SS433, the prototype for these so-called microquasars (Fabrika 2004; Cherepashchuk et al. 2005; Begelman et al. 2006; Blundell et al. 2008; Middleton et al. 2021). Indirectly, they have been proposed to give rise to the observed diversity in the X-ray spectra of ULXs as a result of the viewing angle effect (Kaaret et al. 2017; King et al. 2023). Whereas this general pictures holds fairly well qualitatively, we know very little about how much mass and AM is lost with each of the ejecta. Most GW-source population studies assume that all the non-accreted matter is lost through a bipolar outflow or fast wind launched close to the BH, i.e., the isotropic reemission model. This can be viewed as a lower limit on the AM loss1. However, having a fraction of the mass leave the system as an outflow launched far away from the BH (e.g., through the L2 or L3 outer Lagrangian point) would significantly enhance the loss of AM and the degree of orbital shrinkage (Lu et al. 2023). We illustrate this in Fig. 1 as a comparison between the yellow and blue lines2. The blue model ejects 25% of the non-accreted mass through L2 outflows. As a result, it produces a BBH merger with a delay time that is ∼100 times shorter and comparable to the fast-merging BBH systems that would otherwise originate only from CE evolution. The importance of AM loss for the SMT evolution channel has been emphasized and discussed in several recent studies (van Son et al. 2022b; Willcox et al. 2023; Picco et al. 2024; Olejak et al. 2024; Gallegos-Garcia et al. 2024).

The idealized example in Fig. 1, however, does not model the donor star and its reaction to mass loss, which is the necessary step to gauge how much mass is transferred and on what timescale and whether the interaction remains stable. This can be achieved with detailed stellar models of BH+Star systems (e.g., Podsiadlowski et al. 2003; Detmers et al. 2008; Marchant et al. 2021; Gallegos-Garcia et al. 2021; Klencki et al. 2021, 2022; Fragos et al. 2023; Misra et al. 2024). Although numerically more expensive than rapid binary evolution simulations, binary models involving a 1D stellar structure are crucial for realistic predictions from binary channels as, at the moment, these detailed results are not at all well reproduced by rapid GW-source population models (Marchant et al. 2021; Gallegos-Garcia et al. 2021; Klencki et al. 2022).

Previous studies of the SMT channel using detailed binary evolution models of BH+Star systems explored only a limited number of cases and did not investigate the impact of the AM budget uncertainty on the properties of BBH mergers (Marchant et al. 2021; Gallegos-Garcia et al. 2021). Here, we fill this gap by modeling BH+Star systems with the 1D stellar evolution code MESA (Sect. 2.4) in the entire parameter space of masses, periods, and mass ratios in which the SMT channel operates at low metallicity. We explore different assumptions on the orbital AM loss and the resulting shrinkage during mass transfer.

We find that there is a fundamental limit to how tight binary systems can become via stable mass transfer that is robust against uncertainties in binary physics (contrary to expectations outlined in Fig. 1; Sects. 3.1 and 3.2). This orbital separation limit has direct implications for the properties of BBH mergers, in particular delay times and spins (Sects. 3.4 and 4.4). The reason for the limit lies in the stellar structure of the donor star (as opposed to in binary processes), which dictates when the mass transfer becomes unstable (Sects. 3.3 and 4.1). We discuss which types of donor stars can lead to BBH mergers (Sect. 4.2) and how GW astronomy could yield clues into stellar interiors (Sect. 4.3). The results from our detailed models can be applied in rapid binary codes (Sect. 4.5). We conclude our work with a summary in Sect. 5.

2. Methods

2.1. Overview of model grids

We compute detailed binary evolution models of BH+O-star systems, i.e., binaries comprised of a BH and a massive hydrogen-rich star. We calculate two types of model grids: (a) given the mass of the first-formed BH (MBH; 1), grids covering different initial periods and mass ratios of BH+O-star systems; (b) given the mass and radius of a donor star, grids exploring different mass ratios to determine the critical mass ratio for SMT of the donor. For the first type of grids, we explored BH masses MBH; 1 = 4, 7, 10, 13, 16, 20, 24, 28, 32, 36, and 40 M⊙. For each MBH; 1, we considered periods and mass ratios from a wide enough range to capture the entire parameter space for the formation of BBH mergers through SMT. As the range is not known a priori, for the first few MBH; 1 masses we evolved BH+O-star systems for all the initial periods that lead to mass transfer (from ∼1 to 1000 days). Most of the grids were computed at metallicity Z = 0.1 Z⊙ = 0.0017. In addition, for MBH; 1 = 10 M⊙ we explored several different metallicities from Z = 0.4 Z⊙ to Z = 0.01 Z⊙. The BH+O-star grids are summarized in Figs. D.1 and D.2. For the second type of grids, we explored donor masses from 10 to 100 M⊙ and two assumptions on the efficiency of semiconvection: αsc = 33 (the same as in the BH+O-star grids) and αSC = 0.01. The choice of semiconvection affects the evolutionary stage of donors (see Sect. 2.4), which has an impact on the mass transfer evolution and BBH merger formation (Sect. 3.3). In addition, for both types of grids we considered two variations (three for MBH; 1 = 10 M⊙) on how much AM is carried away with the non-accreted matter during mass transfer, introduced in Sect. 2.2. To better understand the results of these detailed binary models and compare with rapid binary-evolution methods, in Sect. 2.3 we introduce a semi-analytical model to estimate the outcome of mass transfer evolution. Our stellar evolution computations terminate at central-carbon depletion (Sect. 2.4). In Sect. 2.5 we detail our assumptions on further evolution until the core-collapse and the formation of the secondary BH.

2.2. Orbital evolution during stable mass transfer

Through considerations of the orbital AM in an interacting BH+Star system with a circular orbit3, one can express the rate of the separation change as

where a is the semi-major axis (separation), Mstar is mass of the mass-losing star (the donor), MBH is mass of the accreting BH (the accretor), β is the fraction of the transferred mass that is accreted, and γ parametrizes the specific AM of the non-accreted matter, hloss, in units of the orbital AM Jorb:

For a circular orbit,  . The value of γ depends on how the non-accreted matter is lost from the system. The assumption that it is ejected from the close proximity of the BH, carrying its orbital AM, gives

. The value of γ depends on how the non-accreted matter is lost from the system. The assumption that it is ejected from the close proximity of the BH, carrying its orbital AM, gives

The assumption that the mass is lost through the outer Lagrangian point L2 can be approximated with

where aL2 is the distance from the L2 to the center of mass. Its value slowly depends on the mass ratio and can be approximated as aL2 ≈ 1.2a (Pribulla 1998). The L2 point is located on the outer side of the BH for mass ratios Mstar > MBH (the usual case throughout the paper), with the L3 point then located on the outer side of the donor. For mass ratios Mstar < MBH, the location of the L2 and L3 points becomes swapped. Here, for simplicity, we only consider the mass loss through L2, regardless of the mass ratio. This is justified because, as we show, in BBH merger progenitors the mass ratio Mstar/MBH never becomes lower than ∼1/3, in which case γL2 does not deviate from γL3 by more than 25%.

Finally, mass lost with the wind of the donor corresponds to γstar = MBH/Mstar. Mass loss with the specific AM of the entire orbit would correspond to γorbit = 1.0. Equation (1) only considers the AM associated with the orbit, neglecting the internal AM from the spin of the star or the BH because typically Jspin; BH ≪ Jspin; star ≪ Jorb4. The Jspin; star term is accounted for in our detailed binary models (Sect. 2.4).

As the orbit is expected to stay (nearly) circular during an SMT phase, the loss of orbital AM directly affects the orbital separation (Jorb2 ∝ a) and the larger the γ, the more the orbit shrinks or the less it expands. For BH-star systems with Mstar > MBH we have γstar < γorbit < γBH < γL2. This is why mass loss through stellar winds (γstar) expands the orbit, non-conservative mass transfer with mass loss from the proximity of the BH (γBH) shrinks the orbit5, and any L2 outflows (γL2) enhance the orbital shrinkage even more.

Throughout the paper, we consider the case where γ can be divided into three components:

where fwind + fbipolar + fL2 = 1. In this case a fraction fbipolar of the non-accreted mass is ejected from near the BH (as a bipolar outflow/jet or via fast disk wind), fraction fL2 is lost from near the L2 point, and fraction fwind is lost from the system with the wind of the donor star. Most of the time, we have fwind ≪ 1 (i.e., the wind is negligible). We explore three scenarios:

-

Fiducial treatment: γ ≈ γBH. Here, the mass is ejected from the proximity of the BH with no L2 outflows.

-

Enhanced orbital shrinkage: γ ≈ 0.8γBH + 0.2γL2. In this case, ∼20% of the mass is ejected through L2.

-

Extreme orbital shrinkage: γ ≈ 0.45γBH + 0.55γL2. For this case, ∼55% of the mass is ejected through L2.

The exact fractions of mass lost through L2 in the medium or high AM loss models depend on the mass ratio of the binary, as described in detail in Appendix C.

2.3. Semi-analytical model for a mass transfer phase

To better understand the results obtained in detailed binary models, we develop a semi-analytical model to calculate the outcome of an SMT phase. This method is similar to the way in which the SMT is treated in rapid binary-evolution codes widely used for GW-source population synthesis. The main two differences with respect to MESA binary models are: (a) mass transfer stability, which in MESA is obtained self-consistently for each individual binary while rapid codes rely on prescriptions, and (b) the effect of mass transfer on the donor’s core mass (Schürmann et al. 2024; Shikauchi et al. 2025).

We consider a binary comprised of a BH and a massive hydrogen-rich star (MO; Star), which we refer to as a BH+O-star system. The star initiates an SMT phase when the orbital separation is aini. For simplicity, we assume circular orbits. The product of this interaction in a binary with a BH and a massive He-rich star (MHe; Star): a BH+He-star system. The final separation is

where the expression for da/dMstar can be found by combining Eqs. (1) and (5). To compute the integral in Eq. (6), one needs to know how much mass was lost from the star (MHe; star), whether via wind or mass transfer, as well as what were the accretion efficiency (β) and the specific AM of the non-accreted matter (γ). Briefly, to obtain MHe; star at the end of the mass transfer, we assume that the donor has lost 90% of its H-rich envelope. After the SMT phase, the He-star will continue to lose mass via winds, which we estimate knowing its approximate luminosity and the remaining lifetime (typically ∼core-He burning) based on single stellar tracks. We describe our set of assumptions and methodology further in Appendix A.

2.4. Detailed MESA binary models

We employed the MESA stellar evolution code (Paxton et al. 2011, 2013, 2015, 2018, 2019; Jermyn et al. 2023)6. We modeled the evolution of BH+O-star systems and begin our simulations at the zero-age MS (ZAMS) of the stellar component. We thus assumed that the companion evolves as a normal, single star (in reality it had most likely been a mass gainer in a past mass transfer prior the first BH formation). The evolution was followed throughout the entire mass transfer phase (or until the mass transfer becomes unstable) and later until the central carbon depletion.

We applied the mixing-length theory (Böhm-Vitense 1958) with mixing length α = 1.5, the Ledoux criterion for convection, and semiconvective mixing with an efficiency of αSC = 33 (Schootemeijer et al. 2019)7. We accounted for convective core-overshooting during H- and He-burning with a step overshooting length of σov = 0.33 in the fiducial model (as calibrated by Brott et al. 2011). In addition, in Sect. 3.3 we considered a variation with a severely reduced efficiency of semiconvection αSC = 0.01. The choice of semiconvection affects whether the transition to the core-He burning phase occurs in the blue (high semiconvection) or in the red part of the HR diagram (low semiconvection; see Stothers & Chin 1992; Georgy et al. 2013; Schootemeijer et al. 2019; Klencki et al. 2020). The variation with αSC = 0.01 allows us to explore a case in which blue supergiant donor stars are less evolved (pre-core He burning) compared to our default assumption of αSC = 33. While it is convenient to vary αSC to explore this effect, there are other uncertain factors that affect the radial expansion of massive stars (rotational-mixing, convective-boundary mixing, mass loss) and the transition from blue to red supergiants is an open problem of stellar astrophysics (see Sect. 4.3 and references therein). To help converge models approaching the Eddington limit, we applied a reduction of superadiabacity in radiation-dominated regions using the new implicit method from Jermyn et al. (2023)8. Stellar winds were modeled following the approach of Klencki et al. (2022), comprised of various recipes for H-rich stars (Nieuwenhuijzen & de Jager 1990; Vink et al. 2001) and He-rich stars (Nugis & Lamers 2000; Hainich et al. 2014; Tramper et al. 2016; Yoon 2017). In addition, based on Gräfener & Hamann (2008), we enhanced the mass loss rates for H-rich stars from Vink et al. (2001)9 for stars approaching the Eddington limit to account for the transition to optically thick winds (Vink et al. 2011; Bestenlehner et al. 2014; Sander et al. 2020, see also). We modeled rotationally induced mixing and internal angular-momentum transport via Taylor-Spruit dynamo, Eddington-Sweet circulation, secular shear instabilities, and the Goldreich-Schubert-Fricke instability, with a combined efficiency factor fc = 1/30 (Heger et al. 2000; Brott et al. 2011). We included rotationally enhanced mass loss as in Langer (1998). Tidal interactions follow the synchronization timescale for radiative envelopes from Hurley et al. (2002). The mass transfer rate was calculated following the scheme by Marchant et al. (2021) and the accretion rate was Eddington-limitted. The scheme self-consistently accounts for L2 and L3 outflows when the size of the donor reaches the L2 or L3 equipotential. In practice, this happens only briefly during instances of very rapid mass transfer and the amount of mass lost via L2 or L3 this way is very small (≪1%). Here, we model the fraction of mass ejected through L2 (fL2) as possibly being much higher, with fL2 = 0.0, ∼0.2, or ∼0.55 (following the three AM loss models introduced in Sect. 2.2; see also Appendix C for exact fL2 values). The higher fL2 values account for the possibility of a substantial amount of mass and AM leaving the accretor’s Roche lobe in the form of slow and mostly equatorial outflows, rather than as fast bipolar disk winds or jets. This become especially important at the highly super-Eddington mass transfer rates of BH-OB systems (Ṁ/ṀEdd ∼ 104; e.g., Lu et al. 2023). Apart from L2 outflows, the rest of the non-accreted matter is ejected with the specific AM of the BH (γBH; Sect. 2.2). Mass lost in stellar winds is lost with the specific AM of the star (γstar).

We assumed a maximum mass transfer rate Ṁmax = 10−0.5 M⊙ yr−1, above which the mass transfer is deemed to become unstable and to soon enter a CE phase. Although somewhat arbitrary, the choice of Ṁmax does not strongly affect our results, as we discuss in Sect. 4.1. We let the MESA calculations continue above the Ṁmax threshold and find that in most of the cases that surpass this critical rate, the value of Ṁ keeps increasing rapidly to ≳1 − 10 M⊙ yr−1, at which point the models crash. The physical justification for determining stability based on a threshold mass transfer rate is that once a certain Ṁth;crit is reached, the timescale of mass loss is shorter than the timescale needed to thermally re-adjust the surface layers and rebuild a stabilizing entropy gradient, which facilitates an even more rapid further increase in Ṁ that is found in 1D stellar models (Temmink et al. 2023). The value of Ṁth;crit varies across donors of different mass and radius, typically exceeding ≳0.1 M⊙ yr−1 for massive donors, which is ∼10 − 100 times larger than their thermal-timescale mass-transfer rate (see Fig. 4 in Temmink et al. 2023). A different stability criteria adopted in the literature is based on a critical relative rate of change Adyn of the orbital separation or the mass transfer rate over a single orbital period P, i.e., unstable if max(|Ṁ/M|,|ȧ/a|)P > Adyn, with Adyn = 0.02 (Pavlovskii & Ivanova 2015; Pavlovskii et al. 2017) or Adyn = 0.05 (Temmink et al. 2023). Our criteria of Ṁmax = 10−0.5 M⊙ yr−1 corresponds to Adyn ranging from ∼0.0001 for P ≈ 1 day to ∼0.1 for P ≈ 1000 days, meaning that we may be optimistic in assessing stability in wide orbits (P ≳ 200 days). For systems assumed to enter a CE phase, we calculated the envelope binding energy of the donor and estimate the CE survival based on the energy budget formalism, assuming αCE = 1.0 (similarly to Klencki et al. 2021).

2.5. From the end point of MESA to BBH mergers

To put the BH+He-star systems obtained in our binary models in the context of BBH mergers, we assume that the massive He-star always collapses to form a second BH. To illustrate how the final orbital separations relate to BBH delay times, we make a simplifying assumption that the secondary BH forms in direct collapse, with no natal kick or mass loss (whether in baryons or in neutrinos). The only exception is that we account for pair-instability induced mass loss for the most massive stars (carbon-oxygen cores MCO > 38 M⊙) using fits from Renzo et al. (2022), based on models by Farmer et al. (2019). This results in the most massive BHs of around ∼43 M⊙ (but see Farag et al. 2022). The presence of non-zero kicks of BHs or mass loss at BH formation would affect the predicted merger times, potentially allowing for a small population of fast merging BBH even from relative wide but eccentric orbits (see our Appendix B, Vigna-Gómez 2025, and the Appendix in Marchant et al. 2016). To calculate the merger time of a DCO system we follow the analytical fit from Mandel (2021), based on Peters (1964).

2.6. Determining critical mass ratios and minimum orbital separations

Using the numerical MESA setup and mass transfer stability criteria described in Sect. 2.4, we determine critical mass ratios for donor stars with masses from 10 to 100 M⊙. To this end, we first simulated a grid of 15 single-star evolutionary tracks from 10 to 100 M⊙, at Z = 0.1 Z⊙ metallicity (see Fig. D.3 for the HR diagram). For each stellar track, we consider the entire range of its radial expansion as the possible donor stars for mass transfer in binaries. Every 0.1 dex in radius of the single-star track (i.e., ∼20 − 25 times for each mass), we copy the exact stellar structure into a binary MESA model to examine its behavior as a donor. The companion is set to be a point mass and the initial orbit is set to be circular with a separation such that the copied star is about to fill its Roche lobe. We explore many different mass ratios Mdonor/Maccretor, ranging from 1 to 12, with the goal of finding the critical mass ratio qcrit: the largest q for which the mass transfer remains stable. We did so in an iterative way: We began with a sparse grid of mass ratios with Δq = 2, found the largest q (lowest q) for which the mass transfer remains stable (becomes unstable), narrowed down the search to mass ratios between those two values, and decreased Δq. After three to four such iterations, we steadily converged to qcrit. We followed this procedure and employed three variations: a fiducial SMT model with γ = γBH, a model with enhanced AM loss due to L2 outflows (γ ≈ 0.8γBH + 0.2γL2), and a model with γ = γBH and low efficiency of semiconvection, αSC = 0.01 (as opposed to αSC = 33 in all the other grids). Ultimately, for each initial mass-radius of the donor, we determined qcrit with accuracy Δq ± 0.02 for the fiducial model and Δq ± 0.1 for the variations with L2 outflows and low efficiency of semiconvection. We computed about 30−40 models with different q values for each mass-radius pair, making it about 20 000 MESA binary models for both variations, with the results presented in Figs. 5 and 6.

|

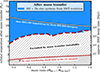

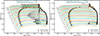

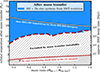

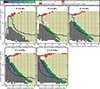

Fig. 6. Formation of BBH mergers is a probe of internal chemical mixing in stars and of the stellar structure. We plot the minimum BBH delay times from SMT evolution given the donor mass (at ZAMS) and radius (at RLOF) for two variations in the efficiency of semiconvective mixing in stars (αsemiconv.). Only cases with the BBH delay time below ≲13.7 Gyr (yellow-brown regions) are potential GW sources. The range of donors that may lead to BBH mergers is severely reduced in the variation with low efficiency of semiconvection (right panel) and it shows a preference for high-mass donors (≳40 M⊙). This is because the chemical structure of donor stars determines the conditions for delayed-dynamical instability and therefore affects the critical mass ratios, the minimum post-SMT separations, and BBH delay times (Sect. 4.2). This is different from the assumptions on the orbital AM loss that only affects the qcrit (Fig. 5). The difference between stellar models in both panels is closely connected to the blue supergiant problem (Sect. 4.3). The thick blue line shows the transition from MS to post-MS donors. Several main types of donors are labeled (Hertzsprung gap, core-He burning, convective envelopes, He-rich envelopers); see text. Based on MESA models of BH+O-star binaries evolving through SMT at the critical mass ratio q = qcrit. See Fig. D.2 for post-SMT separations. |

3. Results

3.1. From BH+O-star systems to BBH mergers: Semi-analytical and detailed binary evolution models

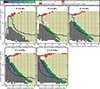

Here, we analyze the evolution of BH+O-star systems with different initial orbital periods and mass ratios to investigate which of them form BBH mergers. To develop intuition, we begin with the rapid semi-analytical method for mass transfer evolution (Sect. 2.3) in the left panel of Fig. 2, before moving to results from detailed MESA binary models. We consider BH+O-star systems with initial periods from ∼1 to 1000 days (Y axis; wider orbits would be non-interacting systems) and mass ratios MBH; 1/MO; Star from 0.1 to 0.5 (X axis). The initial BH mass is always MBH; 1 = 10 M⊙, meaning the initial O-star mass ranges from 20 to 100 M⊙. In each binary, as the O-star evolves and expands, it will eventually initiate mass transfer onto the BH. By that point, the period and mass ratio have changed slightly from the initial values due to winds. For the purpose of the semi-analytical exercise, we consider the mass transfer to be always stable and simply mark the potential stability criteria at critical mass ratio qcrit = ≈0.28 (dashed vertical line, after Riley et al. 2022 who follow Ge et al. 2015). For simplicity, we assume fully non-conservative mass transfer (β = 0) as the mass transfer rates expected in BH binaries with massive donors are generally highly super-Eddington (Podsiadlowski et al. 2003; Rappaport et al. 2005). Indeed, in our MESA models with Eddington-limited accretion we find β ≲ 0.1. We assumed that the non-accreted matter is ejected from near the BH (γ = γBH). For each BH+O-star system, we calculate the final post-SMT separations afin according to Eq. (6). Assuming the secondary collapses to form the second BH (Sect. 2.5), we obtain the corresponding BBH merger delay times. The results are in the left panel of Fig. 2, where we color-code the parameter space of BH+O-star binaries according to the final outcome of SMT evolution. The two solid blue lines mark which BH+O-star binaries would reach the final separation afin = 2 R⊙ or 25 R⊙, which is approximately the range of orbits required for BBH systems to merge within the Hubble time. Importantly, both the afin values and the final outcomes in the left panel assume that the mass transfer is always stable, which in reality is not case. In most rapid binary codes, the stability criteria is comprised of a set of critical mass ratio values (or their corresponding critical ζcrit = d log RRL/d log Mstar exponents); see also Sect. 4.5. A fixed critical mass ratio for stability would mean excluding systems to the left of a vertical line in Fig. 2, as illustrated by a dashed red line example at qcrit = 0.286 ≈ 1/3.5 in the left panel. This choice of qcrit corresponds to the stability criteria for radiative giants in the COMPAS code (assuming non-conservative mass transfer, γ = γBH, and their ζcrit = 6.5, Vigna-Gómez et al. 2018; Riley et al. 2022).

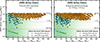

|

Fig. 2. Window for the formation of BBH mergers as predicted by semi-analytical and detailed binary models. Colors mark the evolutionary outcomes of interacting BH+O-star systems across different initial periods and mass ratios, calculated with our semi-analytical rapid model of SMT evolution (left panel; Sect. 2.3) and compared with MESA binary models for two different assumptions on orbital shrinkage during mass transfer: fiducial (γ = γBH, center) and enhanced shrinkage due to L2 outflows (right). The initial BH mass is always MBH; 1 = 10 M⊙ and metallicity is Z = 0.1 Z⊙ (see Fig. D.1 for other BH masses). Wide-non interacting systems are not shown. Solid blue lines mark systems in which the SMT evolution would lead to final orbital separation afin = 2 R⊙ or 25 R⊙, according to the semi-analytical model, which is approximately the range of separations needed for BBH mergers. The dashed red line is the boundary between stable and unstable mass transfer. The outcomes of the semi-analytical model are only applicable if the mass transfer is stable. In rapid codes, it is typically assumed to be related to a critical mass ratio (the vertical line at qcrit ≈ 0.28, left panel). In the MESA models, the stability is determined self-consistently at every timestep, and it is found to be entirely different. The mass transfer only remains stable in systems where the final separation is afin ≳ 10 R⊙. This conclusion is robust against uncertainties of SMT evolution and holds even if enhanced orbital shrinkage is assumed (right), leading to BBH mergers with long delay times ≳1 Gyr (Sect. 3.4). |

The area between the afin = 2 R⊙ and 25 R⊙ lines in the left panel of Fig. 2 marks the potential parameter window for the formation of BBH mergers, colored by the BBH delay time. The dark dotted area on the left are systems that would technically produce BH+He-star systems with separations < 2 R⊙. In such orbits, even the naked He-star would overflow its Roche lobe, potentially leading to a merger and a transient (Metzger 2022; Klencki & Metzger 2025) or reducing the He-core mass so substantially that it never forms a BH, unless the interaction can be cut short (e.g., by core collapse or the orbit widening). Finally, the light yellow region are systems in which the SMT evolution would lead to the formation of wide non-merging BBH systems. The stability requirement of q > qcrit reduces the parameter space for BBH merger formation to initially short-period systems (≲10 day) that interact on the MS, i.e., case A mass transfer. Coincidentally, the treatment of case A evolution in rapid codes has been shown to suffer particularly significantly from the necessary simplifications of the rapid method, under-predicting the final core mass and over-predicting the amount of mass transferred (Belczynski et al. 2022; Romero-Shaw et al. 2023; Shikauchi et al. 2025; Schürmann et al. 2024).

The results from MESA binary models are presented in the other two panels of Fig. 2, for both the assumption of low AM loss during SMT (fiducial model, γ = γBH) as well as the enhanced AM loss due to L2 outflows (γ ≈ 0.8γBH + 0.2γL2). Here, we focus mainly on the final evolutionary outcomes of these models and the question whether the mass transfer has remained stable and the final separation is close enough to form a merging BBH system. We refer to Marchant et al. (2021) for a detailed overview of the evolutionary pathway from BH+O-star systems to BBH binaries, and to Podsiadlowski et al. (2002, 2003) for a general discussion of mass transfer rates and interaction timescales in BH binaries. Each rectangle in Fig. 2 represents one MESA binary model. Non-interacting wide systems are not shown. Models in which the mass transfer remains stable and the second BH forms are color-coded according to the BBH delay time, with non-merging wide BBHs shown in yellow. Models in which the mass transfer becomes unstable are labeled either as “common envelope” (for convective-envelope donors, Pini ≳ 700 day) or as “BH and Star merger” (for radiative-envelope donors, Pini ≲ 700 day). This choice is based on the expectation that unstable mass transfer and CE evolution with radiative donors lead to stellar mergers (Kruckow et al. 2016; Ivanova et al. 2020; Klencki et al. 2021; Marchant et al. 2021)10. The two blue solid lines mark the parameter space for BBH merger formation found in the semi-analytical model (afin = 2 and 25 R⊙ in the left panel), adjusted for the value of γ. Notably, the upper boundary coincides with the widest MESA models that form BBH mergers. This indicates that the orbital evolution in the semi-analytical model generally agrees well with the orbital evolution in MESA, with the exception of mass ratios q ≳ 0.15 and initial periods P ≲ 3 day (for γ = γBH). The first case is mass transfer from very massive donors (> 70 M⊙), which in MESA transfer a lower amount of mass before detaching compared to ΔMstar = 0.9 Menv assumed in the rapid method, such that the orbit does not shrink as significantly. The second case, i.e., short-period systems, are binaries following early case A mass transfer evolution, which in MESA produce lower secondary BH masses compared to our rapid method due to the core mass reduction (Schürmann et al. 2024).

The striking difference between the rapid and detailed binary models is in the mass transfer stability (red dashed lines in Fig. 2). In MESA calculations, the stability threshold for radiative-envelope donors (P ≲ 700d) is not at all a vertical line that would correspond to any critical mass ratio qcrit, or even a combination of several qcrit values. Instead, the stability line spans a wide range of mass ratios and depends on the size of the orbit: The longer the orbital period, the more stable the mass transfer in BH+Star systems (see also Marchant et al. 2021; Gallegos-Garcia et al. 2021). This result agrees with the findings of Ge et al. (2015, 2020, 2024) who have found that critical mass ratios vary significantly as massive stars expand such that interactions in wider orbits (with more expanded radiative giants) are more stable.

The mass transfer (in)stability found in detailed models directly affects the properties of BBH mergers. Most of the potential parameter space for BBH merger formation is excluded due to instability (BH + Star merge). The BBH mergers that do form in MESA have relatively wide final separations afin between ∼10 and 25 R⊙ (for MBH; 1 = 10 M⊙), leading to long delay times ≳1 Gyr. Surprisingly, this is also the case in the variation with enhanced AM loss due to L2 outflows (right panel). Even though the orbits shrink significantly more and BBH mergers may originate from initially wider BH+O-star systems, no BBH mergers with afin ≲ 10 R⊙ and short delay times are produced. In the following sections we explain this as the fundamental separation limit of the SMT evolution.

3.2. There is a limit: Minimum orbital size from SMT evolution

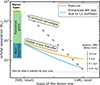

We find that there is limit on how close binary systems can become via mass transfer without triggering dynamical instability, as illustrated in Fig. 3. The figure is based on a grid of detailed MESA binary models of BH+O-star systems with MBH; 1 = 10 M⊙ (same as the right-hand panel of Fig. 2), with similar results found for other BH masses. The hatched region marks the range of separations that we find to be excluded in the SMT channel due to mass transfer instability, with the densely hatched region also excluded in the CE channel. Figure 3 demonstrates that the minimum orbital size of BH+He-star systems from SMT evolution is around ∼8 − 10 R⊙ (periods ∼0.8 day). This has consequences for the properties of BBH mergers: long delay times (≳1 Gyr) and inefficient tidal spin-up at the BH+He-star stage (Sects. 3.4 and 4.4). More broadly, the separation limit from SMT evolution depends on the type of the donor star (Sect. 3.3).We note a trend between the minimum separation of BH+He-star systems and their mass ratio qBH − He; Star = MBH; 1/MHe; Star in Fig. 3. This is because systems with lower qBH − He; Star (i.e., more massive He stars) originate from wider BH+O-star systems, which undergo case B/C mass transfer with donors that are core-He burning stars. We find that mass transfer from such donors may remain stable in tighter orbits than case A interaction.

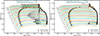

|

Fig. 3. Fundamental orbital separation limit from stable mass transfer (red dashed line) seen in the population of BH+He-star systems formed in MESA binary models. Separations below ∼8−10 R⊙ are excluded in the SMT channel due to mass transfer instability (dashed region, physical origin in Sect. 4.1). As a result, BBH mergers from SMT evolution have long delay times of ≳1 Gyr, and their BH+He-star progenitors tend to be outside the regime of tidal spin-up (P ≳ 0.8 day). Here, the orbital evolution during SMT assumes enhanced AM loss due to L2 outflows with γ ≈ 0.8γBH + 0.2γL2. However, models assuming a different γ yield a similar range of BH+He-star separations (Fig. 4). The solid red line indicates a hard lower limit for the separation of BH+He-star systems in the CE channel, set by the size of a naked helium star. The figure is based on a grid of BH+O-star models with MBH; 1 = 10 M⊙ and Z = 0.1 Z⊙ metallicity, with similar results found also for larger BH masses (Sect. 3.4).

|

Counter-intuitively, the separations of BH+He-star systems from SMT evolution only weakly depend on the degree of orbital shrinkage and the choice of γ. In Fig. 4, we compare the range of periods of BBH merger progenitors before the SMT phase (BH+O-star) and after the interaction (BH+He-star) for three different assumptions on the amount of L2 outflows and the corresponding AM loss. The more mass is lost through L2, the more the orbit shrinks during SMT, meaning that wider BH+O-star systems evolve to become BBH mergers (left panel). This difference can be quite dramatic, shifting BBH merger progenitors from BH+O-star systems on orbits of a few days (case A mass transfer) to wide dormant BH binaries with periods of hundreds of days, essentially covering the entire parameter space for interaction with radiative stars (Klencki et al. 2020). The uncertainty in γ causes a difficulty in predicting which of the observed BH-Star systems are progenitors of GW sources. For comparison, we mark the sample of BH high-mass X-ray binaries and X-ray quiet massive BH-Star systems with known periods and mass ratios: Cyg X-1 (Miller-Jones et al. 2021), LMC X-1 (Orosz et al. 2009), M33 X-7 (Orosz et al. 2007, although see Ramachandran et al. 2022), HD 130298 (Mahy et al. 2022), VFTS 243 (Shenar et al. 2022), HD 96670 (Gomez & Grindlay 2021), and HD 215227 (Casares et al. 2014), although see (Janssens et al. 2023).

At the BH+He-star stage, on the other hand, the orbits are similar across all the variations (right panel). Even with extreme orbital shrinkage, the SMT evolution does not lead to periods below ∼0.6 day, with most BH+He-star systems at P ≳ 1 day. As in Fig. 3, shorter periods (closer separations) are excluded by mass transfer instability. The small differences in BH+He-stars systems in the three variations in Fig. 4 are due to differences in the structure of donor stars interacting at different PBH − O; Star periods, rather than due to the mechanism of orbital shrinkage or the amount of AM loss. As we discuss in the following: it is the star that matters.

3.3. The inside matters: Determining which donor stars lead to short-period systems and BBH mergers

It is not a coincidence that mass transfer becomes unstable in systems heading to orbital separations below ∼8 R⊙. By examining individual cases (Sect. 4.1), we find that in such binaries, a delayed dynamical instability is triggered when the near-core envelope layers of the donor star are being transferred. These layers are located at radial coordinates ∼3 − 10 R⊙ inside the radiative envelope, depending the stellar mass and evolutionary stage. They are characterized by a particularly fast rate of expansion in response to mass loss compared to the rest of the envelope due to their near-flat entropy profile. To keep the mass transfer stable, the orbit cannot continue to shrink significantly anymore when the flat-entropy layers are being stripped. This prevents the formation of BH+He-star systems with separations ≲8 − 10 R⊙ via SMT evolution, regardless of the overall degree of orbital shrinkage from the moment of Roche-lobe overflow (RLOF) and the choice of γ. We discuss the mechanism of near-core instability in more detail in Sect. 4.1.

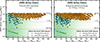

This signals an important point: orbits of BH+He-star systems formed in the SMT channel depend primarily on the donor stars and their inner entropy profiles rather than on the AM loss or accretion efficiency during the SMT phase. The internal structure of stars, on the other hand, can vary greatly depending on the stellar mass and radius, evolutionary stage, and chemical mixing. To examine which types of donors favor the formation of close BH+He-star systems and BBH mergers, we systematically compute mass transfer evolution from stars of different mass (from 10 to 100 M⊙) and size (the entire range of radial expansion) at Z = 0.1 Z⊙. For each mass-radius pair of the donor, we determine the critical mass ratio for SMT evolution qcrit following methodology described in Sect. 2.6. The result is shown in the upper panels of Fig. 5 for two variations: with fiducial SMT treatment (γ = γBH, left panel) and with enhanced AM loss (γ ≈ 0.8γBH + 0.2γL2, right panel).

|

Fig. 5. Minimum orbital size from SMT evolution is primarily determined by the donor star, rather than by binary physics. Here, we report the critical mass ratios qcrit for BH+O-star systems (top panels), final orbital separations in binaries with qRLOF = qcrit (middle panels), and their corresponding BBH delay times (bottom panels), calculated with MESA for a grid of donor stars of different mass (at ZAMS) and radius (at the onset of RLOF) at Z = 0.1 Z⊙. The separations and BBH delay times shown here can be viewed as the minimum values achievable from SMT evolution given the donor mass and radius. Left panels follow the fiducial SMT treatment with γ = γBH, right panels assume enhanced orbital shrinkage due to L2 outflows. While enhancing the orbital shrinkage (left vs right) affects the critical mass ratios, the post-SMT orbits and their corresponding BBH delay times remain nearly unchanged. This is because these final outcomes are primarily determined by the stellar structure of the donor, which is the same in both variations. For illustrative purposes, the BBH delay times assume that each donor collapses to form the second BH, no matter its final core mass. Only the systems with delay times below ∼13.7 Gyr (i.e., brown in the bottom panels) are potential BBH mergers and GW sources for the LIGO/Virgo/Kagra detectors. The scatter points indicate the explored grid of donor masses and radii. For each pair, the qcrit value was found iteratively via binary MESA models down to at least ±0.1 accuracy. |

The qcrit values we find in Fig. 5 have several characteristics. For a given donor mass, qcrit increases as a function of the donor radius all the way until the donor develops an outer convective envelopes (≳200 − 700 R⊙, depending on the mass). At that point, qcrit rapidly decreases. We also see a slow trend with mass: the more massive a donor, the larger its qcrit values. This is consistent with the prior large-scale studies of mass transfer stability, which also discuss the origin of those trends in detail (Ge et al. 2015, 2020, 2024). Notably, both these past as well as our results indicate that an assumption of a single qcrit value for radiative or convective donors is an oversimplification, as the trend with radius is strong. Finally, we observe that all the qcrit values decrease when enhanced AM loss is assumed (right vs left in Fig. 5). This is fully expected, as the more AM that is lost, the more rapidly the orbit shrinks, and therefore the more unstable the mass transfer is. While it is possible to analytically compute correcting factors to qcrit given any chosen γ such that the rate of shrinkage at the onset of RLOF is the same11, these values would not be correct because the instability is not determined at the moment of RLOF but at some later stage, a priori unknown.

In the central panels of Fig. 5, we show the orbital separations at the end of SMT in binary models with q = qcrit as a function of the initial donor mass and its radius at RLOF. These can be viewed as the minimum orbital size of BH+He-star system that may be formed as a result of SMT evolution, given the donor star12. As we are interested in close-orbit BH+He-star systems, we focus the color-scale on the range of separation from 8 to 100 R⊙, without resolving the wider orbits of systems that underwent SMT with convective donors. Assuming that all the He-stars collapse to form the secondary BHs (Sect. 2.5), we further compute the delay times of the resulting BBH systems and color-code the result in the bottom panels of Fig. 5. Delay times ≲13.7 Gyr (brown) are BBH systems that merge within the age of the Universe. We find that donors with masses ≲20 M⊙ do not lead to BBH mergers, which may set the lower mass limit for the SMT channel.

Figure 5 reveals a surprising result: whereas the critical mass ratios change significantly when varying the assumption on γ (left vs right), the minimum orbital separations and BBH delay times from SMT evolution remain virtually unchanged. In other words, BH+He-star orbits in the SMT channel appear to be robust against the major uncertainties of orbital evolution during SMT, which is a rare case in binary astrophysics. It also suggest that for radiative donors, the physical origin of instability is more closely related to the orbital evolution at advanced stages of mass transfer (and therefore the final orbit), rather than to the initial rate of orbital shrinkage at RLOF. We discuss this in the context of delayed-dynamical instability and stability criteria in Sect. 4.1.

In addition, the post-SMT orbital separations in Fig. 5 show a complex behavior rather than a simple trend with mass or radius. The corresponding BBH delay times indicate that for some donor stars, the SMT channel cannot lead to sufficiently close orbits to produce BBH mergers (i.e., tdelay > 14 Gyr), even for the most favorable case of q = qcrit. It turns out that the donors that “do not work” in the SMT channel can be identified as several distinct types of stars and linked to evolutionary stages and envelope characteristics. We do so in Fig. 6, where we re-plot in more detail the minimum BBH delay times (for q = qcrit) obtained from different donors in our Fiducial model (left panel) and compare with a model variation with a severely reduced efficiency of semiconvective mixing αsemiconv. = 0.01 (right panel). We choose to vary semiconvection as it is a known factor to affect the evolutionary types of giant donors in 1D stellar models (Schootemeijer et al. 2019; Klencki et al. 2020; Kaiser et al. 2020)13. The thick blue line in Fig. 6 marks the boundary between MS and post-MS donors.

The largest donors with R ≳ 500 − 700 R⊙ are red supergiants with outer convective envelopes. They are the most prone to unstable mass transfer, with low qcrit values. The SMT evolution in their case leads to wide BH+He-star orbits of hundreds of R⊙ and delay times ≫14 Gyr. Instead of SMT, these donors may lead to NS or BH mergers via CE evolution (Kruckow et al. 2016; Klencki et al. 2021).

The other post-MS stars are radiative-envelope giants. They can be split into two categories (Klencki et al. 2020): Hertzsprung gap (HG) donors that engage into mass transfer right after the end of MS, as a result of a rapid envelope expansion when the core contracts, and Core-He burning (CHeB) donors that initiate mass transfer at a more advanced evolutionary stage, as a result of a slow nuclear-timescale expansion during the core-He burning phase. We find that this distinction plays a crucial role in the SMT channel. As it turns out, all the post-MS donors that cannot produce BBH mergers (tmerge > 14 Gyr in Fig. 6) are HG donors. On the other hand, CHeB donors lead to delay times as short as ∼300 Myr. As we discuss in Sect. 4.1, the reason lies in the different inner entropy structure of HG and CHeB stars. As a result, the mass transfer from HG donors leads to higher mass transfer rates and is less stable than from CHeB donors. Even the smallest orbital separations of BH+He-star systems from HG donors are comparatively quite large (≳20 − 30 R⊙), whereas CHeB donors may lead to systems with ∼8 R⊙ orbits (Fig. 5).

The significance of the HG vs CHeB distinction becomes apparent when comparing both panels of Fig. 6. In the variation with reduced efficiency of semiconvection (right), all massive stars expand rapidly at the end of the MS and consequently all the radiative post-MS donors are of the HG type (Schootemeijer et al. 2019; Klencki et al. 2020). They do not lead to the formation of BBH mergers via the SMT channel, nearly completely quenching the role of post-MS mass transfer. It is not a surprise that a variation in assumptions behind 1D stellar models lead to somewhat different outcomes, but it is rare for an uncertainty in the inner structure of stars to have such a strong effect on GW-source predictions. Whether massive stars interact as HG or CHeB donors is closely related to the long-standing debate on the nature of blue supergiants, as we discuss in Sect. 4.3.

The MS donors are weakly affected by the change in semiconvective mixing (Fig. 6) or the γ variation (Fig. 5). We find that most MS donors with M ≳ 20 M⊙ and R > 10 R⊙ can lead to BBH mergers via SMT evolution (at Z = 0.1 Z⊙ here), although with long delay times of a few gigayears. In fact, case A mass transfer may be the dominant mode of formation of BBH mergers in SMT evolution, especially above the total BBH mass of 40 − 50 M⊙ (Fig. 7). While the BBH delay times from MS donors are generally ≳2 Gyr, the delay times from CHeB donors may be as short as ∼300 Myr. That means that counter-intuitively, the most narrow BH+He-star orbits may be formed from initially the widest BH+O-star binaries with MO; Star > MBH (Fig. D.4)14.

|

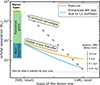

Fig. 7. BBH mergers from the SMT channel have long delay times (≳1 Gyr) as a consequence of the fundamental separation limit, regardless of the uncertainties in binary orbit evolution (left vs. right). Here, we plot the delay times of merging BBHs from SMT evolution (tmerge ≲ 13.7 Gyr) from all our binary MESA grids, as a function of the total BBH mass. We distinguish between BBH mergers formed via SMT evolution from MS donors (case A mass transfer) and post-MS donors (case B or C). Notably, case A evolution dominates for massive BBH mergers (≳40 M⊙). Two variations are considered: non-accreted mass ejected with the specific AM of the BH (γ = γBH) and enhanced AM loss due to L2 outflows (γ ≈ 0.8γBH + 0.2γL2). The BBH delay times are unaffected by the choice of γ. The green shading indicates the approximate range of delay times and masses where we expect the CE channel to contribute. The figure is based on MESA binary grids of BH+O-star systems with the firstly formed BH initial mass of MBH; 1 = 4, 7, 10, 13, 16, 20, 24, 28, 32, 36 M⊙, and 40 M⊙ (see Fig. 2 for details and Appendix D for other masses). |

We find that there are two types of MS donors that do not lead to BBH mergers (Fig. 6). The first are O-type stars in very close BH binaries that overflow their Roche lobes with RRLOF ≲ 10 R⊙ (periods ≲2 days). These donors generally engage into mass transfer when they are still early during their MS evolution. As a result, their He-core mass decreases with respect to a single star or a post-MS donor (Schürmann et al. 2024). This leads to the orbit reexpanding in the later half of the case A mass transfer due to the mass ratio reversal (see also the left panel of Fig. D.4), and BBH delay times significantly above 14 Gyr. We note that this late reexpansion of the orbit can be reduced with enhanced orbital AM loss, for example due to L2 outflow (comparing left and right of Fig. 5). While the regime of ∼1 day orbits may not be the most suited for the SMT channel, it could be where the CHE channel for BBH mergers takes over (de Mink & Mandel 2016; Mandel & de Mink 2016; Marchant et al. 2016).

Finally, we find that very massive stars (≳80 M⊙) may not be suitable as donors for the SMT channel once they expand beyond ∼50 − 100 R⊙. This comes as a surprise, given that these stars are characterized by the most extreme critical mass ratios of even up to 9 (top of Fig. 5). In principle, they should thus be the ideal candidates for enormous orbital shrinkage during the SMT phase and the formation of BBH mergers (as also found in our semi-analytical model). However, what detailed MESA models reveal is that the very massive stars do not transfer much mass before detaching from the SMT phase, never allowing the orbit to shrink significantly. This is because their envelopes are already He-enriched even without any mass transfer due to more extended MS convection and stronger mass loss. As a result, stars of ≳80 M⊙ transfer only ∼20 − 30% of their mass before contracting to ≲20 R⊙, which in wider orbits leads to an early detachment from mass transfer. This amount of transferred mass is far less than what is assumed is any rapid binary evolution model. After detachment, the partially stripped He-enriched star is a hybrid between a normal single star and a fully stripped helium core, making it extremely difficult to model without detailed 1D stellar computations. This phenomena of the mass transfer stopping early was discovered by Sen et al. (2023) as a scenario to form reverse Algol systems, i.e., post-interaction binaries in which the mass-loser remains more massive than the mass gainer. Observationally, such stars would likely appear as H-rich Wolf-Rayet stars of the WN type (Pauli et al. 2022). In the context of binary evolution scenarios, an early detachment from mass transfer would have significant consequences. It may indicate that binary interactions do not have as strong an effect on the properties and orbits of very massive stars in ≳100 day systems as they do on normal massive stars systems even up to ∼1000 days. Binary channels, such as the SMT pathways to BBH mergers, may become less effective in the regime of very massive stars. Without a better understanding of internal chemical mixing and stellar winds of very massive stars it may be impossible to arrive at robust predictions for GW sources from binary channels (for a discussion of these challenges in the CE channel see Romagnolo et al. 2025).

3.4. Consequences for the properties of BBH mergers

So far in Sect. 3.1, we examined the formation of BBH mergers from BH+O-star MESA models with MBH; 1 = 10 M⊙. We found BBH delay times of ≳1 Gyr, regardless of the degree of orbital shrinkage during SMT and the assumption on γ (Sect. 3.2). We argued that the key factors determining BBH orbits in the SMT channel are instead the evolutionary stage and envelope structure of donor stars (Sect. 3.3). Here, we combine results from MESA grids of BH+O-star systems with other BH masses: MBH; 1 = 4, 7, 10, 13, 16, 20, 24, 28, 32, 36 M⊙, and 40 M⊙ (see Fig. D.1 for a collection of grid figures, all at Z = 0.1 Z⊙ metallicity). For each MBH; 1 case, we simulated a range of periods and mass ratios that is large enough to capture the entire parameter space for the formation of BBH mergers (notably, the range changes with mass, Fig. D.1). Two variations were explored: the fiducial SMT treatment with γ = γBH, and variation with enhanced orbital shrinkage due to AM loss through L2 outflows (γ ≈ 0.8γBH + 0.2γL2). As we do not model the prior distribution of BH + O-type systems formed in Nature, we do not make predictions for the formation rate or the mass distribution of the observable population of BBH sources (however, see the discussion in Sect. 4.4). Instead, in Figs. 7 and 8, we demonstrate what is the entire possible range of BBH masses, delay times, and mass ratios that may be realized in the SMT channel given our assumption of direct collapse with no natal kick (in Appendix B and Vigna-Gómez 2025 we discuss how BH kicks may affect our results).

|

Fig. 8. Mass ratios of BBH mergers from SMT evolution are confined to the range from ∼0.3 to ∼3, determined by the physics of stable binary interactions. We plot the BBH mass ratios qBH − BH as a function of the BBH mass from our binary MESA grids, where qBH − BH is defined as MBH; 1/MBH; 2 and with MBH; 1 (MBH; 2) as the mass of the first (second) born BH. Hatched regions indicate the combinations of BBH masses and mass ratios that cannot be produced via SMT evolution (see text). This results in a positive trend between qBH − BH and Mtot. Circles indicate models in which the SMT interaction was initiated by a MS donor (case A) and diamonds mark SMT evolution from a post-MS donor (case B or C). The color indicates the orbital period at the BH+O-star stage (i.e., before the SMT). Based on binary grids of BH+O-star systems with MBH; 1 = 4, 7, 10, 13, 16, 20, 24, 28, 32, 36 M⊙, and 40 M⊙. |

In Fig. 7, we show the BBH delay times as a function of the total BBH mass for all the BBH mergers formed across our MESA binary grids. In two panels we compare both γ variations, confirming that the enhanced orbital shrinkage from L2 outflows does not lead to shorter delay times across all the BBH masses. We distinguish between BBH mergers formed via SMT evolution from MS donors (case A mass transfer) and post-MS donors (case B or C). Green shading indicates where we expect the CE channel to contribute, assuming that it falls off at the high-mass end as indicated by the empirical lack of red supergiants with masses ≳40 M⊙ (Davies et al. 2018); see also Klencki et al. (2021). For the SMT channel, we find that MS donors always leads to long BBH delay times of ≳2 Gyr, whereas post-MS donors (specifically CHeB giants) may lead to tighter BBH systems and shorter delay times of a few hundred megayears. This is in line with our investigation of different donor types and structures (Sect. 3.3; see also the discussion in Sect. 4.1). In addition, we find that BBH mergers with the total mass above ∼40 M⊙ form predominantly from case A mass transfer. This is because of the large radii of MS stars above the mass of ∼50 − 60 M⊙ in our models, such that the case A interaction occurs even in wider orbits of hundreds of R⊙ (Fig. 6). While the radii of these massive MS stars are likely overly inflated in 1D stellar models (Sanyal et al. 2015, 2017; Klencki et al. 2020; Agrawal et al. 2020; Romagnolo et al. 2023), we find that very massive stars in wider binaries (i.e., typical case B/C range) are not efficient in forming BBH mergers via the SMT channel due to their He-rich envelopes causing an early detachment (Fig. 6). Our results suggest that case A evolution may be the dominant formation channel of massive BBH mergers via SMT evolution. This poses a challenge for the SMT treatment in rapid binary evolution codes to accurately predict the cores and final masses of case A donor stars (Belczynski et al. 2022; Romero-Shaw et al. 2023; Schürmann et al. 2024; Shikauchi et al. 2025).

In Fig. 8, we examine the mass ratios of BBH mergers as a function of their total mass. We define the mass ratio qBH − BH as MBH; 1/MBH; 2, meaning that qBH − BH > 1 are systems in which the firstly formed BH is the more massive, and vice versa. Similarly to Fig. 7, we include BBH mergers formed across all our BH+O-star grids. They are arranged along several discrete curves, each corresponding to a different MBH; 1, ranging from 4 to 40 M⊙. In black, we mark BBH systems in which one of the BHs would exceed the pair-instability limit (Farmer et al. 2019; Renzo et al. 2022, although see Farag et al. 2022), while red is the regime of BH + NS mergers assuming an upper NS mass limit at 3 M⊙. Hatched regions indicate the combinations of BBH masses and mass ratios that are not produced by SMT evolution according to our models. We find that the exclusion of high qBH − BH systems (i.e., the secondary-formed BH being notably less massive) is due to insufficient orbital shrinkage during SMT. For BBH mergers to form with such mass ratios, the companion stars at the BH+O-star stage could not be too massive with respect to the BH, which prevents the orbit from shrinking during SMT. This limitation is partly alleviated if enhanced AM loss is assumed (the right panel), though even in this case none of the BBH mergers exceed qBH − BH ≈ 3. More extreme BBH mass ratios could potentially be obtained if a substantial amount of mass is lost during the formation of the BH (i.e., non-direct collapse), although the resulting Blaauw kick would further increase the already long delay times that we find (see Appendix B). On the other end of the spectrum, BBH mergers with very low qBH − BH would require BH+O-star systems in which the stellar companion is substantially more massive than the BH, leading to significant orbital shrinkage during the SMT phase and a wide pre-SMT orbit. We find that such BBHs do not form in the SMT channel, particularly at high masses, because interactions with very massive donors (≳75 M⊙) in wide orbits do not lead to close post-SMT orbits (see Fig. 6 and donors with He-enriched envelopes).

Figure 8 reveals a positive trend between qBH − BH and Mtot. However, it is unclear to what extend this effect might be realized in the measured population of BBH merges. Observationally, it is impossible to infer which BH was formed first, meaning that the qBH − BH > 1 values would instead be measured as 1.0/qBH − BH, negating the existence of any trends.

4. Discussion

4.1. The physical reason behind the limit on orbital tightening via SMT

In this section we discuss the following questions: (a) Why is there a limit on how close the post-SMT orbital separation can be, and what determines the ∼8 R⊙ value? (b) Why does the limit remain unchanged even if enhanced orbital shrinkage due to strong AM loss through L2 is assumed?

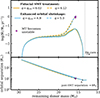

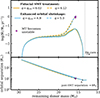

In Fig. 9 we examine mass transfer evolution from a 30 M⊙ donor interacting in systems with BH companions of different masses. The mass ratio at RLOF qRLOF = Mdonor/MBH varies from qmin = 1.5 to qmax = 12. The donor is the same for each qRLOF: a core-He burning giant of 252 R⊙ at 0.1 Z⊙ metallicity with a ∼17 M⊙ envelope and a ∼13 M⊙ core15. We chose this particular donor as it leads to the smallest post-SMT orbit of ∼8 R⊙. The top panel in Fig. 9 shows the mass transfer rate evolution as a function of the decreasing envelope mass. Models reaching log(Ṁ/M⊙ yr−1) > 0.5 are assumed to become unstable. The model with qRLOF = qcrit = 6.06 (shown in bold) is the critical one, i.e., at the threshold between stable and unstable mass transfer evolution, leading to the smallest post-SMT orbital separation. In the remaining two panels of Fig. 9, we show the internal entropy profiles of the donor star from the critical model, plotted every 1.5 M⊙ from the onset of RLOF (dark red, left) to near the end of the mass transfer (dark blue, right).

|

Fig. 9. Origin of the separation limit lies in delayed dynamical instability. Top: Mass transfer rate (Ṁ) in systems with a 30 M⊙ donor and a varying mass ratio at RLOF, shown as a function of the decreasing envelope mass. The donor is the same for each mass ratio at the onset of RLOF: ∼250 R⊙ core-He burning giant with a ∼17 M⊙ envelope and ∼13 M⊙ core. Models reaching log(Ṁ/M⊙ yr−1) > 0.5 become unstable (Sect. 2.4), as indicated by the dashed horizontal line. The critical mass ratio for stability is qcrit = 6.06 (marked in bold). The threshold between stable and unstable models is determined by the Ṁ peak at Menv ≈ 2.5 M⊙. Middle: Internal entropy profiles of the donor in the q = qcrit model, ranging from the onset of RLOF (light, left) to the end of mass transfer (dark, right). The Ṁ peak seen in the top panel is caused by stripping off the layers where the entropy profile is nearly flat. Bottom: The same entropy profiles but as a function of the radius coordinate. The flat entropy layers are within the inner 3 R⊙ of the donor (6 R⊙ during the Ṁ peak), causing instability in models in which the mass transfer would shrink the orbit below a ≲ 8 R⊙. |

We analyze how the mass transfer rate Ṁ evolves across models of different mass ratios. Systems with qRLOF ≤ 6.06 remain stable. For most stable mass ratios (qRLOF < 5.5), the Ṁ peaks once about 30% of the envelope has been transferred (here at the envelope mass ∼12 M⊙). In the remainder of the mass transfer phase, the rate is smaller and may even drop to the nuclear-timescale Ṁ ≈ 10−0.5 M⊙ yr−1. This is consistent with prior models of stable mass transfer evolution (e.g., Podsiadlowski et al. 2002; Rappaport et al. 2005; Pavlovskii et al. 2017; Klencki et al. 2022). However, as the mass ratio of the model increases (qRLOF > 5.5), we begin to observe a delayed Ṁ peak appear at late stages of the interaction, when the final ∼5 M⊙ of the envelope are being transferred. The delayed Ṁ peak rises in magnitude the higher the mass ratio and eventually triggers instability for qcrit = 6.08. Notably, among models with qRLOF near the qcrit value, the peak mass transfer rate varies strongly as a function of qRLOF. For example, comparison models with qRLOF = 5.98, 6.08 (critical), and 6.12, their maximum reached Ṁ values are ≈0.025, 0.34, and 1.1 M⊙ yr−1, respectively. This indicates that our choice to set the critical rate Ṁcrit at 10−0.5 M⊙ yr−1 has a small effect on qcrit, at least for post-MS donors. For the MS donors the uncertainty on qcrit due to instability criteria is larger.

Figure 9 illustrates that it is the delayed Ṁ peak at Menv ≈ 2.5 M⊙ that determines the transition from stable to unstable MT evolution and the critical mass ratio. Internal entropy profiles of the donor (middle panel) reveal that this Ṁ peak is associated with deep envelope layers in which the entropy profile is nearly flat. This is a well-known effect: the flatter the entropy profile, the more the donor star expands in response to mass loss, leading to higher mass transfer rates (for a perfectly constant entropy, the donor would react as dlnR/dlnM = −1/3, Paczyński et al. 1969; Paczyński & Sienkiewicz 1972; Webbink 1985). Mass transfer instability caused by a flattening entropy profile in deep stellar interiors has been identified as delayed dynamical instability already by Hjellming & Webbink (1987).