| Issue |

A&A

Volume 706, February 2026

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A295 | |

| Number of page(s) | 28 | |

| Section | Interstellar and circumstellar matter | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202556740 | |

| Published online | 19 February 2026 | |

Photoevaporation can reproduce extended H2 emission from protoplanetary disks imaged by JWST/MIRI-MRS

1

Dipartimento di Fisica, Università degli Studi di Milano,

Via Celoria, 16,

20133

Milano,

Italy

2

Université Paris-Saclay, CNRS, Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale,

91405

Orsay,

France

3

Leiden Observatory, Leiden University,

PO Box 9513,

2300 RA

Leiden,

The Netherlands

★ Corresponding author: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

4

August

2025

Accepted:

19

December

2025

Context. Understanding the dispersal of protoplanetary disks remains a central challenge in planet formation theory. Disk winds driven by magnetohydrodynamics (MHD) and/or photoevaporation are now recognized as primary agents of dispersal. With the advent of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), spatially resolved imaging of these winds, particularly in H2 pure rotational lines, have become possible, revealing X-shaped morphologies and integrated fluxes of ∼10−16−10−15 erg s−1 cm−2.

Aims. However, the lack of theoretical models suitable for direct comparison has limited the interpretation of these features. To address this, we present the first model of photoevaporative H2 winds tailored for direct comparison with JWST observations.

Methods. Using radiation hydrodynamics simulations coupled with chemistry, we derived steady-state wind structures and postprocessed them to compute H2-level populations and line radiative transfer, including collisional excitation and spontaneous decay.

Results. Our synthetic images reproduce the observed X-shaped morphology with radial extents of ≳50-300 au and semi-opening angles of ∼37°-50°, matching observations of Tau 042021 and SY Cha. While the predicted line fluxes are somewhat lower than the observed values, they remain broadly consistent for lower J transitions despite the model not being specifically tailored to these sources.

Conclusions. These results suggest that photoevaporation is a viable mechanism for reproducing key features of observed H2 winds, including morphology and fluxes, though conclusive identification of the wind origin requires source-specific modeling. This conclusion challenges the reliance on geometrical structures alone to distinguish between MHD winds and photoevaporation. Based on our findings, we also discuss alternative diagnostics of photoevaporative winds. This work provides a critical first step toward interpreting spatially resolved H2 winds and motivates future modeling efforts.

Key words: protoplanetary disks / ISM: jets and outflows / photon-dominated region (PDR)

© The Authors 2026

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to support open access publication.

1 Introduction

Protoplanetary disks lose mass not only through accretion onto the central star but also via winds launched from their surfaces, driven by either magnetic forces (e.g., Blandford & Payne 1982; Pelletier & Pudritz 1992; Suzuki & Inutsuka 2009) or photoevaporation (e.g., Shu et al. 1993; Hollenbach et al. 1994). Understanding the mechanisms and relative roles of these winds across evolutionary stages is key to addressing the disk dispersal problem.

Observational evidence of disk winds has accumulated over decades, starting with the detection of blueshifted forbidden lines in optical spectra (e.g., Jankovics et al. 1983; Appenzeller et al. 1984; Edwards et al. 1987) and with further advances in infrared spectroscopy, particularly with Spitzer and groundbased facilities (e.g., the Very Large Telescope and Keck). In Class II sources, most evidence comes from spatially unresolved blueshifted forbidden lines (e.g., [OI], [S II], [N II], and [NeII]), which are commonly seen in T Tauri stars. These lines typically show a high-velocity component (HVC; >50 km s−1) associated with jets and a low-velocity component (LVC; ≲30 km s−1) attributed to disk winds (e.g., Hartigan et al. 1995; Kwan & Tademaru 1995; Cabrit et al. 1999).

The LVC is often decomposed into a broad component (BC; full width at half maximum of FWHM ~ 100 km s−1 and centroid velocities of v > 10 km s−1) and a narrow component (NC; FWHM ~ 30 km s−1, v ~ 3 km s−1) (Rigliaco et al. 2013; Simon et al. 2016; McGinnis et al. 2018; Fang et al. 2018; Banzatti et al. 2019). Assuming Keplerian broadening, the BC likely traces inner magnetohydrodynamics (MHD) winds (0.050.5 au), while the NC likely arises from farther out (0.5-5 au), consistent with either MHD or photoevaporative winds. However, the distinction remains debated (Banzatti et al. 2019; Weber et al. 2020; Whelan et al. 2021).

In addition to ionic and atomic emission, blueshifted molecular lines such as H2 (v = 1-0 S(1); 2.12 μm) and CO (∆v = 1; ~4.7 μm) have revealed slow warm molecular winds launched at radii typical of the inner disk. This H2 line traces slow winds (<20 km s−1) launched from 0.05-20 au (Gangi et al. 2020), with a debated origin of either MHD winds (Panoglou et al. 2012) or photoevaporation (Rab et al. 2022). In contrast, CO emission line profiles generally favor an MHD origin from the inner disk (Pontoppidan et al. 2011; Brown et al. 2013; Banzatti et al. 2022). Narrower blue-shifted absorption features also point to the presence of an outer disk wind (Brown et al. 2013; Banzatti et al. 2022), with the origins remaining unclear.

Prior to the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), spatially resolved observations captured low-velocity winds for a handful of sources via near-infrared and UV emissions of H2 (Beck et al. 2008; Schneider et al. 2013; Agra-Amboage et al. 2014; Beck & Bary 2019; Melnikov et al. 2023) as well as submillimeter CO emission detected by ALMA (Güdel et al. 2018; Louvet et al. 2018; de Valon et al. 2020; Launhardt et al. 2023). Spectro-astrometry further revealed their spatial extents via CO infrared emission and optical forbidden lines from OI and S II (Pontoppidan et al. 2011; Whelan et al. 2021). More recently, VLT/MUSE observations have provided spatially resolved maps of the optical forbidden lines (Fang et al. 2023; Flores-Rivera et al. 2023). These winds typically show a wide, less-collimated geometry surrounding faster, narrower atomic and ionic jets and winds, forming nested onion-like kinematic structures.

Overall, despite significant progress, distinguishing MHD winds and photoevaporation remains a central challenge. This distinction is critical for understanding where and at what rates disk material is removed; identifying accretion-driving mechanisms - since MHD winds can remove angular momentum (Gressel et al. 2015; Bai 2016; Lesur et al. 2023); and testing disk evolution scenarios (Clarke et al. 2001; Suzuki et al. 2016; Pascucci et al. 2020; Kunitomo et al. 2020; Tabone et al. 2022; Manara et al. 2023). Notably, direct confirmation of photoevap-orative winds has remained elusive, though the LVC of [Ne II] has been highlighted as a promising tracer of photoevaporative winds (Alexander 2008; Pascucci & Sterzik 2009; Pascucci et al. 2011; Alexander et al. 2014; Ballabio et al. 2020; Pascucci et al. 2020).

The advent of JWST offers a major opportunity to address these issues thanks to its high spatial resolution and high sensitivity mid-infrared spectroscopy mode. Various wind tracers are accessible with JWST/MIRI-MRS and NIRSpec, including [Ne II], [Ne III], [ArII], [ArIII], H2, and CO (Bajaj et al. 2024; Sellek et al. 2024a; Arulanantham et al. 2024; Anderson et al. 2024; Pascucci et al. 2025; Schwarz et al. 2025b). Among them, pure rotational lines of H2 are especially compelling. Not only are they the primary constituent of disk gas, but these lines can trace spatially extended (≳102 au) warm winds (≲103K), unveiling the nature of molecular winds. Indeed, such extended H2 emission has been revealed by recent JWST observations (Arulanantham et al. 2024; Anderson et al. 2024; Pascucci et al. 2025; Schwarz et al. 2025b).

On the theoretical side, radiation (magneto)hydrodynamical models coupled with chemistry are now available (Wang & Goodman 2017; Nakatani et al. 2018a,b; Wang et al. 2019; Gressel et al. 2020; Komaki et al. 2021; Sellek et al. 2024b; Hu et al. 2025), enabling detailed comparisons with JWST data. Notably, purely hydrodynamical simulations have predicted photoevaporative H2 winds with structures broadly consistent with observations (Nakatani et al. 2018a,b; Komaki et al. 2021; Sellek et al. 2024b), but it remains unclear whether they can quantitatively reproduce the observed morphology and fluxes.

In this paper, we explore how photoevaporative H2 winds manifest in JWST observations of pure rotational lines while aiming to establish the first theoretical framework for interpreting current and future JWST observations. We investigate two core topics: (1) the morphologies exhibited by these H2 lines from photoevaporative winds and (2) the fluxes they produce. To this end, we generated synthetic H2 intensity maps and line fluxes, leveraging radiation-hydrodynamical simulations with post-processing non-local thermodynamic equilibrium (non-LTE) level population calculation and line radiative transfer.

The structure of this paper is as follows: in Section 2 we describe the computational methods. In Section 3, we present the results and answer the core questions. In Section 4, we discuss model limitations and generalization as well as comparisons with recent JWST observations. Finally, Section 5 provides a summary of the main findings.

2 Methods

To generate synthetic H2 intensity maps and fluxes, we adopted a two-step approach. First, we performed a radiation hydrodynamics simulation of a photoevaporating PPD with non-equilibrium thermochemistry to obtain a self-consistent physical structure featuring H2 winds. We then post-processed the result with RADMC-3D (Dullemond et al. 2012), computing non-LTE H2 level populations and performing line radiative transfer for the pure rotational transitions v = 0-0 S(1)-S(9), including the dust opacity.

The hydrodynamics simulation employs a modified version of the PLUTO code (Mignone et al. 2007), incorporating thermochemistry and radiation transfer modules (Kuiper et al. 2010; Kuiper & Klessen 2013; Nakatani et al. 2018a,b; Kuiper et al. 2020; Nakatani et al. 2021, see also Appendix B). The chemical network includes key PDR reactions as well as extremeultraviolet (EUV) and X-ray photoionization and secondary ionization processes. The thermochemistry module has been benchmarked against standard PDR codes and the DALI code (Appendices B.1 and B.2).

To keep this section concise, we summarize the main features of the setup in Section 2.1, with details in Appendix A. Postprocessing methods are described in Section 2.2. We assume axisymmetry and midplane symmetry throughout.

2.1 Hydrodynamics model: Overview

Our fiducial model is a PPD with mass Mdisk = 10−2 M⊙ orbiting a solar mass star (M* = 1 M⊙). We assume a relatively evolved system with a low accretion rate Ṁacc = 10−10 M⊙ yr−1, motivated by the facts that (1) at the early stages, stellar ultraviolet (UV) and X-ray can be heavily screened by disk winds from the inner regions; (2) photoevaporation is expected to dominate disk dispersal at later stages (Pascucci et al. 2020, 2023; Kunitomo et al. 2020; Weder et al. 2023); and (3) low Ṁacc is reported for systems with H2 winds: 6.6 × 10−10 M⊙ yr−1 for SY Cha, 2 × 10−11 M⊙ yr−1 for Tau 042021, and 7.1 × 10−10 M⊙ yr−1 for CX Tau, though the first two estimates have been recently revised and therefore remain uncertain (see Section 4.4). Higher Ṁacc cases are explored in Section 4.3. Note that in our setup, Ṁacc only affects the accretion-generated UV emission as defined below, although in reality it likely also impacts EUV and X-ray emission (Shoda et al. 2025).

The disk is initially in hydrostatic equilibrium and fully molecular (Appendix A.1 for more details). We evolve the system until it reaches a quasi-steady state by solving the equations for gas density ρ, velocities υ = (υr, υθ, υφ), energy, and chemical abundances {yi|i = H, H+, H2,...}. Our approach naturally includes advection of chemical species, which is crucial for accurately capturing photoevaporative H2 winds, where photochemical timescales can be comparable to wind crossing time (Section 3.1).

Our chemical network includes ~140 reactions (Table B.1) among 27 gas-phase chemical species: H, H+, H2, H2+, H−, O, C, C+, CO, e−, He, He+, H3+, CH, CH+, CH2, CH2+, CH3+, CO+, HCO+, OH, OH+, H2O, H2O+, H3O+, O+, and O2. We assumed the elemental abundances of yC = 1.35 × 10 4 and yO = 2.88 × 10−4 for the gas-phase carbon and oxygen, respectively (Jonkheid et al. 2006; Woitke et al. 2009).

The heating processes include EUV/X-ray photoionization heating (Maloney et al. 1996; Wilms et al. 2000; Gorti & Hollenbach 2004; Nakatani et al. 2018a,b), far-ultraviolet (FUV) grain photoelectric heating (Bakes & Tielens 1994), FUV H2 photodissociation heating and pumping (Hollenbach & McKee 1979; Draine & Bertoldi 1996), and FUV CI ionization heating (Black 1987; Jonkheid et al. 2004; McElroy et al. 2013). Cooling processes include HII radiative recombination (Spitzer 1978); HI Lyα cooling (Anninos et al. 1997); fine-structure line cooling by O I, C I, and CII (Hollenbach & McKee 1989; Osterbrock 1989; Santoro & Shull 2006); and H2/CO rovibrational cooling (Galli & Palla 1998; Omukai et al. 2010). Additional heating and cooling includes dust-gas collisional heat exchange (Cazaux & Tielens 2002) and chemical heating and cooling (Hollenbach & McKee 1979; Omukai 2000).

The FUV, EUV, and X-ray transfer was solved by 1D ray tracing along the radial direction (Nakatani et al. 2018a,b). For optical and infrared radiation, a 2D hybrid scheme was used: stellar irradiation via ray tracing and dust (re-)emission via fluxlimited diffusion (Kuiper et al. 2010; Kuiper & Klessen 2013; Kuiper et al. 2020).

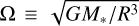

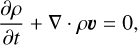

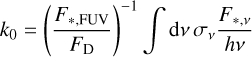

We constructed the spectrum of our 1 M⊙ central star by summing three components: photospheric emission, accretiongenerated UV emission, and high-energy radiation (EUV and X-ray) from the hotter atmospheric components. The photospheric emission was modeled as a blackbody with a bolometric luminosity of L* = 2.34 L⊙ and the effective temperature of Teff = 4278 K (Siess et al. 2000; Gorti et al. 2009). These are typical for a young star (~1 Myr), but our results are not very sensitive to the exact values.

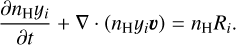

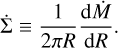

Accretion-generated UV is also represented by a Teff = 104 K blackbody. With Ṁacc = 10−10 M⊙ yr−1 and a stellar radius of R* = 2.61 R⊙ (Siess et al. 2000; Gorti et al. 2009), the resulting accretion luminosity is Lacc = GM* Ṁacc/R* ≈ 1.2 × 10−3 L⊙ ≈ 4.6 × 1030 erg s−1. For the X-ray component, we adopt the modeled X-ray spectrum of TW Hya from the DIANA project (Woitke et al. 2019). Note that TW Hya has a relatively soft X-ray spectrum, which leads to efficient heating at lower column densities. The EUV spectrum is approximated by a linear interpolation between the X-ray flux at 100 eV and the combined photospheric and accretion-originated flux at the Lyman limit (≈13.6 eV). The synthesized stellar spectrum is shown in Figure 1, with the total band-integrated luminosities of LFUV = 9.2 × 1029 erg s−1, LEUV = 2.0 × 1029 erg s−1, and LX = 2.8 × 1030 erg s−1.

We assumed a dust-to-gas mass ratio of 0.01, with 85% of the dust mass in larger grains that have settled toward the midplane. This reduces the abundance of small grains in the upper disk surface, where photoevaporative winds arise. Accordingly, we scaled the rates of dust-gas collisional heat transfer, grain-catalyzed H2 formation by a factor of 0.15. The dust opacity is likewise scaled (see Appendix B for the effects on FUV-driven photochemistry).

We also considered the depletion of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), which are detected in only 10% of PPDs around low-mass stars and are typically underabundant by factors greater than ten compared to the ISM (Geers et al. 2007; Oliveira et al. 2010; Vicente et al. 2013). Since PAHs contribute to grain photoelectric heating (Bakes & Tielens 1994), we scale this heating rate by a depletion factor fPAH. In this study, we adopt fPAH = 0.1. Even lower values do not significantly impact our results at the assumed LFUV.

The simulations were carried out in 2D spherical polar coordinates (r, θ). The computational domain spans r = [0.2,40] × Rg ≈ [1.8, 350] au and θ = [0, π/2] rad, where

(1)

(1)

is the gravitational radius for gas at T ≈ 104 K. We used Nr × Nθ = 144 × 160 grid cells, with logarithmic spacing in the radial direction. In the polar direction, uniform spacing is applied, but with different resolutions below and above θ = 1 rad: each region is divided into 80 cells to provide the finer resolution necessary to resolve the sharp pressure gradient within the disk.

Integration was performed using operator splitting: the hydrodynamics update was applied first - where advection and adiabatic cooling were added - followed by radiative transfer and thermochemistry. In the thermochemistry step, temperature and chemical abundances were updated simultaneously using an implicit Newton-Raphson scheme.

|

Fig. 1 Stellar spectrum adopted in our fiducial model. The vertical dashed lines mark the lower energy limits of the FUV and EUV bands. The lower limit of the X-ray band is 100 eV. (See also Table 1 for the integrated luminosities.) The thin green line shows the photospheric emission, which overlaps with the blue line below 6 eV, for reference. |

Simulation setup of the fiducial model.

2.2 Post-process

We post-processed the steady-state structures obtained from our simulations to generate synthetic intensity maps and fluxes for H2 pure rotational lines, specifically from S(1) to S(9) transitions. This involved calculating non-LTE H2 level populations and performing subsequent line radiative transfer using RADMC-3D (Dullemond et al. 2012).

The level populations are computed using the “Optically Thin non-LTE” method, appropriate for the typically optically thin nature of the H2 lines. Only collisional excitation, deexcitation, and spontaneous decay are considered. We neglect H2 pumping by UV, X-ray, and chemical reactions, though the hydrodynamics simulation includes FUV H2 pumping and chemical heating as heating sources (Section 2.1); the impacts of this simplification are discussed in Section 4.2. It is worth noting that while the population calculations do not incorporate line excitation or de-excitation, self-absorption is accounted for in the subsequent line transfer.

Molecular data for H2, including Einstein A coefficients and collisional rate coefficients for collisions with H, para-H2, ortho-H2, e−, and H+ (Roueff et al. 2019; Lique 2015; González-Lezana et al. 2021; Flower et al. 2000, 2021), are taken from the EMAA database1. In the post-processing, we input the density, velocities, temperature, H2 abundance, and the abundances of the collision partners obtained by the simulations. The para-H2 and ortho-H2 abundances are specified by assuming an ortho-to-para ratio of 3.

Unless otherwise noted, we assumed a distance to the source of d = 140 pc. We explored various disk inclinations and both dust-free and dust-obscured line emission cases.

For the fiducial case, we adopted an edge-on view (i = 90°) and neglected dust obscuration to isolate the intrinsic morphology and fluxes. This served as a baseline for comparisons.

Dust-obscured models use RADMC-3D's default silicate opacity and assume a dust-to-gas mass ratio of 0.01, which is about ten times higher than in the hydrodynamics simulation, to probe the upper-end effects of disk obscuration. Comparing these results with the dust-free case provides insight into the impact of intermediate dusty levels. Increasing dust opacity does not alter the thermochemical structures of the H2 winds in our simulation, so this treatment does not affect the internal consistency.

3 Results

We present the hydrodynamics simulation results and discuss the steady-state structures in Section 3.1, followed by an analysis of the system energetics in Section 3.2. Synthetic intensity maps and fluxes at i = 90° without disk obscuration are shown in Sections 3.3 and 3.4, respectively. Section 3.5 examines the density and temperature regimes traced by each line, followed by a rotation diagram analysis in Section 3.6. The effects of disk inclination and disk obscuration are addressed in Section 3.7. Finally, we discuss spectrally resolved line profiles from the models with disk obscuration in Section 3.8.

3.1 Properties of photoevaporative H2 winds

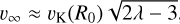

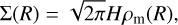

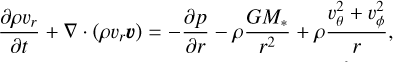

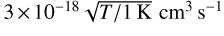

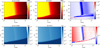

Figure 2 shows a snapshot of the hydrodynamics simulation after the system has reached a quasi-steady state at t ≈ 104yr. Photoevaporative H2 winds are evident in the third panel, where the blueish region marks the H2-dominated region, and white arrows indicate the velocity field. Advection plays a crucial role in shaping this H2 region, highlighting the importance to couple hydrodynamics with chemistry. The typical densities and temperatures of the H2 winds are 102 cm−3 ≲ nH2 ≲ 105 cm−3 and 100 K ≲ T ≲ 1000 K, respectively (the first and second panels). X-ray heating and H2 cooling dominate in the molecular region, while (hard) EUV heating and adiabatic cooling are more important in the atomic/ionic region.

When compared at a similar distance from the star, wind temperature generally anticorrelates with density: hotter winds are less dense. This is because softer X-rays and EUV, which have larger absorption cross-sections, are absorbed at lower column densities and have shorter heating timescales. Besides, atomic and molecular coolants tend to be more abundant at higher column densities and more efficient due to the higher densities. Since photoevaporative winds are pressure driven, higher temperatures generally lead to stronger acceleration and thus higher velocities. As a result, lower-density regions exhibit higher poloidal velocities (compare the top and bottom panels). The low-density wind component (nH2 ≲ 103 cm−3) is mostly supersonic, with poloidal velocities of vp ≳ 1 km s−1.

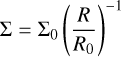

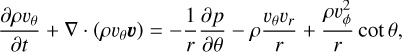

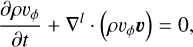

To examine how physical quantities evolve along the flow, Figure 3 presents their profiles along representative streamlines in the H I region (blue), near the H I/H2 boundary (red), and within the H2 region (cyan), launched at ≈3, 40, and 100 au, respectively. The profiles are plotted as functions of the streamline coordinate s, with s = 0 marking the base, defined as the point where the Mach number reaches M = 0.025 (see Appendix C for details). Figure 4 similarly shows the specific heating and cooling rates along the representative streamlines, including only the major contributing processes.

The flow near the H2 dissociation front (e.g., red streamline in Figure 3) originates from the disk surface at R ≈ 40 au, consistent with the critical radius at T ≈ 300 K. This gas travels roughly along the front, accelerating from <0.1 km s−1 to 4 km s−1 (Panel e). It takes ≈1000yr for this gas to exit the computational domain after leaving the disk surface. During the travel, gas density decreases monotonically from nH2 ≈ 105 cm−3 to ≈102 cm−3 (Panel c), while the temperature steadily increases from ≈102 K to 700 K over a distance of ≈ 100 au, and then levels off, nearly constant from that point to the outer computational boundary (Panel d). X-ray and EUV heating are the dominant heating processes (middle panel in Figure 4).

This gas is launched as fully molecular (Panel d), with H2 molecules gradually destroyed via X-ray photoionization as well as two X-ray-driven dissociation pathways. The first pathway (hereafter Path 1) involves proton transfer and dissociative recombination of hydrogen-bearing species: H2+ + H2 → H3+ + H, followed by H3+ + e → 3 H. In this sequence, H2+ is produced via X-ray photoionization, and two H2 molecules are destroyed per photoionization event. The second pathway (Path 2) proceeds through a series of ion-neutral and dissociative recombination reactions of oxygen-bearing ions: (i) H2 + OH+ → H2O+ + H, (ii)H2 + H2O+ → H3O+ + H, and (iii) H3O+ + e → OH + 2H. Here, OH+ in step (i) is generated through H+ + OH → OH+ + H and H2 + O+ → OH+ + H, where O+ is created via charge exchange, H+ + O → O+ + H.

The hydrogen ion is provided by X-ray photoionization H + hν → H+ + e (and to a lesser extent by ion-neutral reaction H + H2+ → H2 + H+). In total, three hydrogen molecules are destroyed per photoionization event, although this number effectively reduces to two when H2+ ends up with the ion-neutral reaction H + H2+ → H2 + H+. FUV photodissociation is negligible under the adopted stellar parameters.

The overall timescale of these dissociation processes is limited by the X-ray photoionization timescale (~3000yr). During the outflow, the H2 abundance drops from yH2 ≈ 0.5 (fully molecular) to yH2 ≈ 0.2 by the time the gas reaches the outer computational boundary, on a timescale of ≈ 1000 yr.

Gas launched beyond R ≈ 40 au remains largely fully molecular (e.g., cyan streamline in Figure 3). In this region, X-ray photoionization timescale increases rapidly with radius, due to both geometric dilution and absorption, outpacing the modest rise in the winds’ crossing timescales (see the fourth panel in Figure 2). The ionization timescale is ≳103 yr, yet X-ray photoionization remains a key H2 destruction process, along with the ion-neutral reaction H2+ + H2 → H3+ + H (Path 1).

Along streamlines, the H2 abundance gradually decreases by ~10% until leaving the computational domain on a timescale of ≈4000 yr. The gas density, temperature, and velocity follow similar trends to those found near the H2 dissociation front described above, albeit with less steep gradients (cyan lines in Figure 3). At these large distances, only X-ray heating remains effective due to the high column density, providing nearly all of the energy input (right panels in Figure 4).

In contrast, gas launched from within R ≈ 40 au undergoes substantial H2 depletion before being strongly accelerated (e.g., blue streamline in Figure 3). Here, the X-ray photoionization proceeds faster (≲103 yr), and the dominant destruction pathway shifts to the oxygen-bearing ion reactions (Path 2). In the innermost regions (a few au), the neutral-neutral reaction H2 + O→ OH + H also contributes, being efficient at high temperatures (activation energy ≈3150K). This inner atomic gas reaches T > 103 K (see the second panel of Figure 2), and shows steep gradients in density, temperature, and velocity along streamlines (blue lines in Figure 3). It attains the highest wind speed of ≈10 km s−1 and exits the computational domain within ~300yr. In this highly irradiated regime, energy losses via radiative cooling are negligible, and nearly all input energy is converted into the mechanical energy (left panels in Figure 4, and see also Figure C.2).

For reference, the cumulative mass-loss rates are estimated to be ≈1 × 10−9 M⊙ yr−1 in total (including helium), and ≈0.4 × 10−9 M⊙ yr−1 for H2. H2 accounts for nearly all hydrogen-bearing mass loss beyond ≳40 au, contributing about ≈70% of the total mass loss there. (See Appendix D and Figure D.1 for details).

|

Fig. 2 Snapshot of H2 density (top), gas temperature (second), H2 abundance (third), and poloidal velocity (bottom). Cyan contours indicate isosurfaces for each quantity: nH2 = 10, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107cm−3; T = 200, 500, 1000, 2000, 3000, 5000K; yH2 = 10−4,10−3,10−2,10−1; and vp = 1,2,5,10,20,30km s−1. In all panels, the white and green dashed contours denote the H2 dissociation front (yH2 = 0.25) and the isothermal sonic surface, respectively. White arrows indicate the velocity field (direction only, not its magnitude) and are omitted where T < 100K. In the H2 abundance map, the dotted gray contour marks the HI ionization front (yHII = 0.5). |

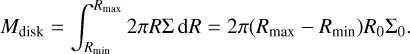

3.2 Energy budget

We examined the energetics of photoevaporative H2 winds, which can offer a useful diagnostic for assessing a photoevap-orative origin (Sections 4.1 and 4.4). The underlying principle is that in a photoevaporating system, a fraction of stellar UV and X-ray photons is absorbed and converted into heat, part of which is subsequently radiated away through H2 line emission. This leads to the energy constraint

(2)

(2)

where LUVX is the total UV and X-ray luminosity; εheat(< 1) is the heating efficiency, defined as the fraction of LUVX converted into heat; and LH2 is the total H2 rovibrational line luminosity, or equivalently the total H2 cooling rate, from the UV- and X-ray-heated region.

In our model, LUVX = 3.9 × 1030 erg s−1, and the total luminosity is dominated by X-rays (Table 1). Integrating the rates of all photoheating processes throughout the computational domain yields a total heating rate of 1.6 × 1029 erg s−1, with X-rays, EUV, and FUV responsible for 1.1 × 1029 erg s−1, 4.7 × 1028 erg s−1, and 3.3 × 1027 erg s−1, respectively. This gives εheat = 4%, consistent with previous radiation hydrodynamics simulations reporting efficiencies of <10% (Wang & Goodman 2017; Wang et al. 2019).

The low efficiency reflects two main factors. First, only O(10%) of the emitted photons are actually absorbed. For instance, X-rays emitted toward low-polar-angle regions, where the column density is low (the dark areas in the top panel of Figure 2), escape the system with minimal absorption. Even in the H2 winds, where the column density is higher, not all photons are absorbed. Full attenuation occurs primarily along the boundary between the disk and wind regions, which subtends only a small solid angle from the perspective of the star.

Second, not all photon energy is converted into heat. A significant portion is lost to ionization and excitation. In the case of ionization, energy losses are substantial if photons have energies near the ionization potentials of the absorbers. For excitation, energy losses typically increase with the photoelectron’s energy (Shull & van Steenberg 1985; Maloney et al. 1996). For X-raygenerated photoelectrons, only ≈10% and ≈40% of the primary electron energy is converted into heat in the HI and H2 layers, respectively (Xu & McCray 1991 ; Maloney et al. 1996, see also discussions in Section 4.5). In the case of FUV photoelectric heating, typically <10% of the absorbed energy is converted into heat, and the efficiency can decrease further as the PAH and very small grain abundances reduce.

In our simulation, LH2 ≈ 1.3 × 1028 erg s−1, accounting for ≈9% of the total heating rate (εheatLUVX ≈ 1.6 × 1029 erg s−1, from X-ray, EUV, and FUV heating at 1.1 × 1029 erg s−1, 4.7 × 1028 erg s−1, and 3.3 × 1027 erg s−1, respectively), and thus LH2 ≈ 3.3 × 10−3LUVX. Strictly, LH2 includes contribution from the innermost region (≲3 au), where the gas temperature is maintained at ≳100K through dust-gas collisional heat exchange, indicating that the energy source for H2 emission is not limited to UV and X-ray irradiation, but also includes stellar optical radiation, which heats the dust grains. However, in our simulation, the contribution from this inner region is negligible compared to that from the UV- and X-ray-heated layers. It is therefore reasonable to consider UV and X-rays as the primary energy sources for LH2.

Note that our analysis does not account for energy absorbed within the inner boundary (≲1.8au). As such, the efficiencies derived here are applicable beyond ≈2au. For consistent comparison with observational estimates, the observed efficiency should likewise exclude contributions from within ≲2 au.

Additionally, while we find LH2 ≈ 3 × 10−3LUVX in the fiducial model, energy efficiency is generally luminositydependent, with typically more deposited energy going into total radiative cooling as luminosity increases (Nakatani et al. 2024). Caution is therefore advised when applying the derived efficiencies to sources with significantly different luminosities. We revisit this point in Section 4.3.

|

Fig. 3 Physical properties along streamlines. (a) H2 abundance map (same as Figure 2) with selected streamlines shown in gray. Three representative streamlines are marked in blue, red, and cyan. (b-f) Profiles of cylindrical radius, densities, temperature, poloidal velocity, and H2 abundance along the three streamlines, using consistent color coding. The horizontal axis indicates the distance along each streamline, with s = 0 defined at the base. In panel c, solid and dashed lines show H2 and hydrogen nucleus densities, respectively. |

|

Fig. 4 Specific rates of major heating and cooling processes along the blue, red, and cyan streamlines in Figure 3, shown from left to right. Labels indicate: EUV photoionization heating (“EUV”); X-ray photoionization heating (“X-ray”); line cooling from O I, H2, and CO; and adiabatic cooling (“adi”). (See Figure C.2 in Appendix for the heating and cooling rates of other processes.) |

|

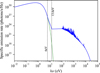

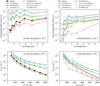

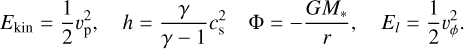

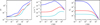

Fig. 5 Intrinsic morphologies of the H2 pure rotational lines (S(1)-S(9)) for a disk viewed edge-on (i = 90°) without disk obscuration. The colors indicate the frequency-integrated intensities, with individual color bars scaled independently in each panel, Right ascension and declination offsets are shown assuming a source distance of d = 140 pc. |

3.3 Intrinsic H2 line intensity maps

In this section, we present the integrated intensity maps, postprocessed with RADMC-3D, to examine the morphology of photoevaporative H2 winds, one of the central focuses of this study. We first analyze the case with i = 90° and no disk obscuration, which reveals the intrinsic emission structure and fluxes. This serves as a reference for more observationally realistic scenarios with different inclinations and disk obscuration, discussed later in Section 3.7.

Figure 5 displays the frequency-integrated intensity maps for the H2 S(1)-S(9) lines, all exhibiting an X-shaped morphology with a central emission peak. The X-shaped structure originates from warm H2 gas (≳100K; see Figure 2), where thermal excitation is efficient. The X-arms trace regions of peak column density in an edge-on view, extending outward with slight collimation and a convex curvature, i.e., the semi-opening angle narrows with increasing distance. This morphology reflects the underlying temperature and H2 distributions (second and third panels in Figure 2).

The emission becomes increasingly compact and slightly more collimated from S(1) to S(9), reflecting the underlying density distribution and the radial and angular temperature gradients. Higher excitation lines require higher densities and trace hotter gas, which resides at smaller radii and lower polar angles (second panel of Figure 2).

The central emission peak originates from the hot, high-density atmosphere of the inner disk (r ≲ 3 au). Note that our computational domain excludes r ≲ 1.8 au where hot, even denser atmosphere likely exists, so the peak emission may be underestimated.

To quantify the morphology, Table 3 lists three key metrics of the images in Figure 5: (i) the emission extent rext, defined as the radius enclosing 95% of the total flux; (ii) the geometric radius Rgeo, where a linear fit to the wind emission intersects the disk midplane, following Pascucci et al. (2025); (iii) the semi-opening angle θopen, defined as the polar angle where the emission peaks at each radius. Since θopen varies with the radius, Table 3 reports both the mean value θ̄open and a log-linear fit: θopen = θ0-θ1 log(r/100 au). The fit uses data from r > 20 au to exclude the inner region. For consistency with Pascucci et al. (2025), Rgeo is measured using points ~0.2" above and below the midplane. Overall, rext and θ̄open decrease with decreasing wavelength. Rgeo also decreases for S(2)-S(9), although S(1) shows a further drop due to its distinct emission geometry (see Figure 5).

To evaluate point spread function (PSF) effects on the geometric indicators, we also measured rext, Rgeo, θopen from images convolved with 2D Gaussians. The FWHMs were set to 0."033(λ/1 μm) + 0.″106 for S(1)-S(8) (Law et al. 2023) and 0.″21 for S(9), estimated using a STPSF simulation tool (Perrin et al. 2014). For Rgeo and θopen, we excluded emission from the inner region (r < 20 au) before convolution to isolate the wind component.

Generally, PSF convolution blurs the convex shapes of the emission, making the morphology appear more as a straight X-shape (Figure 6). This is also reflected in the smaller absolute values of “cnv.” θ1 than the “int.” ones in Table 3.

For θ̄open, the convolution results in a systematic reduction, due to contributions from emission between the arms of the X-shape. The reduction θopen is more significant at smaller radii (r ≲ 50 au), while at larger radii, θopen is mostly unchanged from the intrinsic values.

For Rgeo, the convolution decreases the value across all lines in our model. The negative Rgeo for S(1) originates from the convolution causing the emission peak at each radius to shift systematically upward above the midplane and inward toward the rotational axis, especially within ≲100 au. Near the central region, the convolution mixes contributions from both the arms of the X-shaped structure. The relatively large opening angle further contributes to producing a negative Rgeo. Similar effects are also responsible for the small Rgeo measured in the convoluted S(2) image.

To summarize, PSFs can significantly alter the geometric indicators. Accounting for these PSF-induced biases is essential when interpreting wind-launching points or inferring winddriving mechanisms from morphology.

|

Fig. 6 Comparison of emission morphologies between the intrinsic and Gaussian-convolved S(2) images. Top panel: original image from Figure 5. Bottom panel: same image convolved with a Gaussian kernel of FWHM ∼72 au. |

|

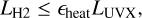

Fig. 7 Integrated fluxes of the S(1)-S(9) lines for the model with i = 90° without disk obscuration and assuming d = 140 pc (black dots). For reference, green crosses indicate the fluxes calculated under the assumptions of LTE and optically thin emission. Observed fluxes for SY Cha (blue; d = 180.7 pc) and Tau 042021 (red; d ~ 140 pc) are also shown for comparison. For SY Cha, we adopted the fluxes measured with a radius aperture of 0.5-2″. Since the spatial integration regions differ between our model and the observations of Tau 042021, and the SY Cha fluxes are not scaled by distance, care should be taken when making direct comparisons (see also Sections 4.4.1 and 4.4.2 and Figure 14). Open circles correspond to the model fluxes with i = 90° but including disk obscuration (Section 3.7; Table 5). |

3.4 H2 line fluxes

Now we turn to the integrated fluxes derived from the intensity maps (Figure 5), which - alongside morphology - represent a key focus of this paper. Figure 7 shows the integrated fluxes (black filled dots) as a function of wavelength, with corresponding values listed in Table 2 with d = 140 pc. The S(1)-S(5) lines, which exhibit extended emission, have fluxes on the order of 10−16−10−15 erg s−1 cm−2. Higher J lines - emitted primarily from the hot, high-density atmosphere of the inner disk (r ≲ 3 au) - are more compact in emission and show fluxes about an order of magnitude lower.

All lines are generally optically thin; only S(1) becomes marginally optically thick near the center, but this has a minimal impact on the image and flux. Most emission arises from the regions close to LTE, making the optically thin plus LTE approximation reasonably accurate.

This is supported by the green crosses in Figure 7, which mark the fluxes computed under the LTE and optically thin assumptions. These fairly agree with the full non-LTE radiative transfer results (black filled dots) within a factor of two across all lines.

For comparison, observed fluxes of Tau 042021 (d ~ 140 pc Arulanantham et al. 2024) and SY Cha (d ≈ 180.7 pc Schwarz et al. 2025a) are also shown (see also Table 2). The overall agreement, especially for lower J lines, is striking. However, we note that the spatial integration domains used to derive the Tau 042021 fluxes are smaller than those in our model, and that the SY Cha fluxes are shown as raw values, without scaling by the distance of d = 180.7 pc. A more detailed comparison follows in Sections 4.4.1 and 4.4.2.

3.5 Gas properties traced by each line

To probe the physical conditions traced by each line, we defined a convenient diagnostic quantity, referred to as the local integrated luminosity,

where νul and Aul are the frequency and Einstein A-coefficient for the J + 2 → J transition, and nu is the upper-level population. This quantity represents the line luminosity contribution from a volume element spanning uniform intervals in ln r, θ, and ϕ.

The physical meaning of LJ may become clearer in its volume-integrated form. Assuming optically thin emission, the integrated line flux is expressed by

so LJ approximately indicates the relative contribution of gas at (r, θ) to the optically thin total flux FJ (or equivalently, the intrinsic total line luminosity). Mapping LJ onto a densitytemperature phase diagram provides the physical conditions traced by each line. We note that LJ and FJ are diagnostic quantities introduced to identify the regions that contribute most to the optically thin total line luminosity and flux, and thus generally differ from those obtained through radiative transfer calculations. However, they become physically equivalent when the line is optically thin and dust extinction is negligible.

Figure 8 shows scatter plots of normalized LJ for each computational cell using the non-LTE level populations computed with RADMC-3D. The dark red-violet points highlight the combinations of nH2 and T contributing predominantly to each line. In general, emission originates from two components: the hot, high-density atmosphere of the inner disk and the more extended, lower-density photoevaporative winds. This dual contribution is consistent with the intensity maps in Figure 5, which show the brightest emission at the center with the extended diffuse emission.

These two regions are roughly separated at r ≈ 3-7 au. For S(5)-S(9), the disk component arises primarily from r ≲ 3 au. We again note that our computational domain excludes the innermost region (r ≲ 1.8 au).

Focusing on the wind (nH2 ≲ 105 cm−3 on the scatter plots), we find that higher excitation lines trace hotter and more rarefied gas. The contributing conditions range from (nH2, T) ~ (105 cm−3,300K) for lower J lines to ~(102 cm−3,900K) for higher J lines. Broadly, the S(1)-S(3) lines primarily trace cooler gas T ~ 200-103K, while the S(4)-S(9) lines are sensitive to warmer regions 700 K ≲ T ≲ 2000 K. Higher temperatures imply higher sound speeds and faster photoevaporative winds. This is visualized by the black contours in Figure 8, which mark poloidal velocities: S(1)-S(3) emission arises in part from slow wind components (~1 km s−1; see Figure 2), while S(4)-S(9) are predominantly associated with faster-moving gas.

|

Fig. 8 Phase-space scatter plots of the normalized local integrated luminosity LJ/LJ,max for each H2 line. Each point corresponds to a computational cell in the simulation, with point size scaled by LJ/LJ,max to reduce overlap and emphasize more emissive regions. The reddish areas highlight the densities and temperatures ranges that most strongly contribute to the total emission. Solid black lines mark approximate contours of poloidal wind velocity (vp = 1, 3, and 5 km s−1), and the green contour indicates the isothermal sonic surface. Dashed blue lines represent the best-fit rotational temperatures (Table 4). |

|

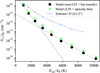

Fig. 9 Rotation diagram of the H2 lines. Black dots show the model results from non-LTE calculations with line transfer using RADMC-3D. The solid and dashed black lines are a two-component fit to the lower J lines S(1)-S(3) and the higher J lines S(4)-S(9), respectively. Green crosses indicate the values assuming LTE and optically thin emission -i.e., the maximum emission possible within our model setup. For reference, observational data for SY Cha are shown with a blue line (Schwarz et al. 2025a). Since the emitting area is not specified in Arulanantham et al. (2024), the data for Tau 042021 are omitted to avoid introducing additional uncertainties. |

3.6 Rotation diagram analysis

We performed a rotation diagram analysis to assess how well the physical properties of photoevaporative H2 winds can be inferred from observations. We then compared the derived temperatures and H2 column densities with those in the simulation.

The analysis fit the integrated fluxes FJ, which are determined by solving radiative transfer, as a function of Eup using

Here,  , gu is the statistical weight, Q is the partition function, Trot is rotational temperature, N̄H2 is the average H2 column density over the emitting region with solid angle Ω.

, gu is the statistical weight, Q is the partition function, Trot is rotational temperature, N̄H2 is the average H2 column density over the emitting region with solid angle Ω.

Figure 9 shows the resulting rotation diagram (black points). We fit the data in two ways: using all transitions S(1)-S(9), and using a two-component approach that divides lower J S(1)-S(3) and the higher J S(4)-S(9) lines. We find that the two-component fit provides a better fit. This reflects the presence of multiple temperature components in the wind, as discussed in Sections 3.1 and 3.5. Figure 9 only shows the two-component fit for clarity.

The best-fit parameters are listed in Table 4. While the level populations are not strictly in LTE, the derived Trot provides reasonable estimates for the temperatures traced by the lower and higher J lines (compare the horizontal blue dashed lines and reddish regions in Figure 8). Similarly, the best-fit NH2 agree well with simulation values: N̄H2 = 3.3 × 1018 cm−2 for 200 K ≲ T ≲ 103K, and 3.7 × 1016 cm−2 for T ≥ 700 K. These agreements are non-trivial, given the non-LTE nature of the emission, but are expected: most emission arises from regions where LTE is a good approximation.

We note that our two-component fit differs slightly from the method used in Schwarz et al. (2025b), where S(1)-S(8) fluxes are fitted simultaneously. This approach does not require pre-defining the boundary between warm and hot components; instead, it naturally emerges from the fit. Applying this technique to our fluxes yields a slightly higher hot-component Trot (≈900 K) because S(4) contributes to both components, lowering the flux attributed to the hot component relative to our segmented two-component fit. This highlights the need for caution when selecting line ranges in a segmented two-component fit to ensure consistency with simultaneous fitting methods.

Comparison of model fluxes for different inclinations with and without disk obscuration.

3.7 Effects of inclination and disk obscuration

From Section 3.3 onward, we have focused on an edge-on disk (i = 90°) and without disk obscuration. Here, we explore how inclination and dust extinction within the disk affect the results.

Inclination alone has little effect on the integrated line fluxes in the absence of disk obscuration, as the emission is optically thin (Section 3.4). Indeed, the fluxes remain nearly constant across inclinations (Table 5), except for a slight increase in S(1) at lower inclinations due to marginal optical thickness at the center. We note that this holds for emission beyond ≳2 au, the region covered by our simulation; stronger inclination dependence may appear for inner regions where intense H2 emission is expected from denser disk atmosphere.

Disk obscuration significantly reduces the flux by obscuring the central and/or far-side regions, depending on viewing angle. For nearly edge-on disks, the midplane is obscured, forming a dark lane and leaving only the vertically extended emission visible, in particular for S(1)-S(3) (Figure 10). This results in a flux reduction by a factor of a few for S(1)-S(6) and by a larger factor for higher J lines S(7)-S(9) (Table 5). The stronger suppression of higher J lines reflects their origin in the hot inner disk atmosphere.

Even reducing the dust-to-gas mass ratio to 0.0015 in the disk only modestly increases the flux: a factor of two for S(9) and less than 50% for the other lines. Compared to the observed fluxes, our model significantly underpredicts the higher J line fluxes (S(7)-S(9)) in the dust-obscured case, though lower J lines remain in relatively good agreement (Figure 7 and Table 2). This suggests that our model may underestimate the higher J line emission from the extended wind component. We revisit this possibility in Section 4.2.

In less inclined disks (e.g., i = 60°; Figure 11), attenuation primarily affects the far side of the disk. This is most noticeable in the S(3) image, where the far-side emission is mostly obscured, due to the silicate opacity enhancement near ≈10 μm. For lower J lines, the morphology shifts from X-shaped to more bowl-shaped with decreasing i.

Flux reductions with respect to the dust-free case vary across transitions, but remain relatively modest - less than a factor of two for all lines (Table 5). Even the higher J lines are only moderately impacted, since the inner emitting regions are not completely obscured.

To summarize, while the morphology transitions from X-shaped (edge-on) to bowl-shaped (face-on), inclination has minimal impacts on the fluxes unless disk obscuration is significant. Dust obscuration becomes important in edge-on systems, leading to: (1) a dark lane in images, (2) corresponding flux reduction for high J lines such as S(7)-S(9) by obscuring emission from the hot inner disk atmosphere. For face-on to moderately inclined disks, the effects are minimal; flux reduction is less than a factor of two.

Given that we may underestimate extended high J emission (Section 4.2), the actual impact of inclination and dust obscuration could be even smaller in real systems. We emphasize that these conclusions apply beyond ≳2 au; emission from the inner regions inside our computational boundary may exhibit a stronger dependence on inclination and disk obscuration. The results also depend on the adopted dust opacity and the degree of settling, and therefore the trends should be interpreted qualitatively.

While edge-on sources help probe wind geometry (e.g., its semi-opening angle), disks at all inclinations may offer comparable insights for the physical conditions of photoevaporative H2 winds. Moderately inclined disks would be particularly advantageous, as they enable complementary comparisons with stellar X-ray and UV luminosities, key diagnostics for photoevaporation (Section 4.1).

|

Fig. 10 Same as Figure 5, but including dust extinction within the disk. The panels show continuum-subtracted images. |

|

Fig. 11 Same as Figures 5 and 10 but for an inclination of i = 60° including dust extinction within the disk. |

3.8 Velocity profiles

We generate spectrally resolved, continuum-subtracted line spectra, using the images of the fiducial model with inclinations of i = 0, 30,45,60,90°. The spectral window spans ±30 km s−1 around the line centers and is sampled with 201 wavelength points (corresponding to a spectral resolution of R ≈ 106). In producing the spectra, we manually exclude emission from the far side of the disk for inclined cases (i < 90°), to isolate the contribution from the near-side surface. The resulting velocity profiles for selected lines are shown in Figure 12.

Overall, low J lines (S(1)-S(4)) exhibit blueshifted, singlepeaked profiles, reflecting strong contributions from the extended wind component. For higher J lines (S(5)-S(9)), emission from the hot, dense atmosphere of the inner disk (R ≲ 3 au) becomes relatively significant (see Sections 3.3 and 3.5). At i < 90°, this leads to high-velocity wings (|v| ≳ 10 km s−1) produced by Keplerian motion in the inner disk atmosphere. At intermediate inclinations (i = 30-60°), the high J line profiles appear flatter and multi-peaked. However, this may partly reflect underestimated high J emission from the extended wind (see also Section 4.2); including it could yield single-peaked, brighter profiles, suppressing the flatter structures. The profiles in Figure 12 also exclude the contribution from the innermost region (≲2au), which is outside our computational domain, and should therefore be interpreted as those arising from the outer disk.

The velocity centroids vcent are generally small (|vcent| ≲ 1 km s−1) across all lines. The FWHMs of single-peaked lines increase with higher J, ranging from 3 km s−1 to 8 km s−1, and broaden slightly with inclination up to i ≈ 60° (by only a factor of ≈1.5), remaining nearly constant at higher inclinations i ≳ 60°. These small |vcent| and narrow widths highlight the slow nature of photoevaporative winds launched from outer radii (Section 3.1) and imply that resolving their kinematics is inherently challenging, even at the highest spectral resolutions (R ≈ 100000; ∆v - 3 km s−1) achievable with current and future instruments such as VLT/CRIRES+ and ELT/METIS.

While vcent below the instrumental resolution can in principle be measured with sufficient signal-to-noise ratio (S/N), detecting a ~1 km s−1 shift at R ~ 100000 requires S/N ≳ 10. CRIRES+ covers the S(8) and S(9) lines and can reach S/N ≈ 10-20 at the line centers with a few-hour integration time, assuming a typical FWHM of ~ 3 km s−1 and line fluxes of ≈10−15 erg s−1 cm−2 for the wind component (see SY Cha fluxes). However, these high J lines may also have substantial contributions from the inner hot disk (Schwarz et al. 2025a), requiring high spatial resolution as well to isolate the wind component. Future > 30 m-class telescopes, like ELT/METIS, will be particularly valuable for disentangling the kinematic signatures of winds to probe their origins.

|

Fig. 12 Velocity profiles of selected lines viewed at inclinations of i = 0° (purple), 30° (cyan), 45° (light green), 60° (yellow), and 90° (red). For i < 90°, the profiles were computed excluding emission from the far side of the disk, isolating the contribution from the near-side surface. |

4 Discussion

In Section 4.1, we recap our main findings and discuss observational diagnostics of photoevaporative winds. Section 4.2 examines the potential impacts of pumping processes on our results. We then explore how the findings may vary with different stellar properties, such as mass and UV/X-ray luminosities, in Section 4.3. In Section 4.4, we compare our models with recent JWST observations and assess whether the observed H2 winds can be explained by photoevaporation, in light of preceding results. Finally, we highlight key caveats in Section 4.5.

4.1 How to tell whether observed H2 winds are photoevaporative or not

Photoevaporation drives H2 winds with a curved dissociation front. The winds typically have H2 densities of 102−105 cm−3 and temperatures of 100-1000 K with the fiducial parameters. This structure results in an X-shaped morphology in the S(1)-S(9) emission when viewed edge-on (Figure 5). The spatial extent of the emission decreases for higher J, from ~300au to ~50au, though the latter may be underestimated (see Section 4.2). The semi-opening angle also decreases for higher J, from ~50° to ~37°, comparable to values observed in Tau 042021 and SY Cha. This suggests a photoevaporative origin remains plausible for these sources, contrasting to the current interpretation favoring MHD winds. Our model demonstrates that geometric indicators such as opening angles and spatial extent are not definitive diagnostics unless the wind is extremely collimated. Given the PSF-induced biases (Section 3.3), caution is essential when using these indicators to estimate wind-launching points or infer wind-driving mechanisms.

Energetics offer a more robust constraint. As discussed in Section 3.2, only ≲10% of the stellar UV/X-ray luminosity is converted into heat, and a small fraction of that (≈9% in our model) is radiated away as H2 emission. This sets an empirical necessary condition for a photoevaporative origin: the observed H2 line luminosity needs to satisfy LH2 ≲ 0.01 LUVX (in our simulation, LH2 ≈ 3 × 10−3LUVX). Exceeding this implies an additional energy source, such as accretion powering MHD winds. Note that this condition applies beyond ≳2 au, as our model excludes energy absorbed closer in; observed efficiencies should be evaluated consistently. Also, this criterion considers only H2 emission from thermal excitation. In practice, higher J levels can be significantly influenced by nonthermal processes (Section 4.2). Therefore, LH2 should be evaluated using lower J lines (e.g., S(1)-S(3)), which have low critical densities. Even when all lines are included in estimating LH2, the total H2 luminosity would still remain below ≲0.1 LUVX, a hard limit for photoevaporative winds, given that only O(10%) of the UV and X-ray luminosity is typically absorbed by the wind (noting again that not all of the absorbed energy is converted into heat, as discussed in Section 3.2).

Wind velocity provides another criterion. Photoevaporative H2 winds typically have poloidal velocities of ~1-5 km s−1. If the H2 emission arises from H I-dominated regions, velocities may reach ≈10 km s−1 but not significantly beyond such speeds, as acceleration is limited past the isothermal sonic point. Thus, a velocity threshold of ≈10 km s−1 serves as a practical upper bound. Accordingly, velocity centroids are expected to remain below this limit, typically on the order of 1 km s−1. In contrast, MHD winds can exceed this range. In the cold MHD wind regime, the asymptotic velocity is given by  , where vK is the Keplerian velocity, R0 is the launching radius, and λ is the magnetic lever arm parameter (Blandford & Payne 1982). For λ ~ 2-5 (e.g., Tabone et al. 2017; Louvet et al. 2018; Gressel et al. 2020; Lesur 2021; Kadam et al. 2025), this yields v∞ - 10-25 km s−1 at R0 ~ 10 au for M* = 1 M⊙. In the magneto-thermal wind regime, where the lever arm is minimal and acceleration is driven primarily by pressure gradients, the radial velocities are typically ≲5 km s−1 (Bai 2017; Wang et al. 2019).

, where vK is the Keplerian velocity, R0 is the launching radius, and λ is the magnetic lever arm parameter (Blandford & Payne 1982). For λ ~ 2-5 (e.g., Tabone et al. 2017; Louvet et al. 2018; Gressel et al. 2020; Lesur 2021; Kadam et al. 2025), this yields v∞ - 10-25 km s−1 at R0 ~ 10 au for M* = 1 M⊙. In the magneto-thermal wind regime, where the lever arm is minimal and acceleration is driven primarily by pressure gradients, the radial velocities are typically ≲5 km s−1 (Bai 2017; Wang et al. 2019).

In summary, key necessary conditions for photoevaporative winds include moderately wide opening angles (see θopen ≈ 30°-50° in the current model), an energy budget satisfying LH2 ≲ 0.01 LUVX, and wind velocities ≲10 km s−1. While such low velocities are very challenging to resolve with JWST, morphology and energetics provide a strong diagnostic framework. These criteria would not rule out MHD winds, but their interpretation remains uncertain without detailed predictions from MHD models.

A systematic survey correlating H2 flux with both UV and X-ray luminosities would be valuable. Moderately inclined disks are optimal targets, enabling both morphological analysis and comparisons with stellar UV/X-ray luminosities. As we discuss later in Section 4.3, for low accretors like the one assumed in the fiducial model, X-rays can dominate the energy input and scale with LH2 (Sections 3.1 and 3.2). For FUV-dominated sources, trends remain unclear: lower J fluxes (e.g., S(1)-S(4)) may weakly anticorrelate with LFUV due to enhanced H2 photodissociation, while for higher J lines, H2 photodissociation and excitation by nonthermal processes (e.g., UV pumping) may compete, making the correlation nontrivial. Further investigation is warranted from theoretical perspectives.

4.2 Missing extended high J line emission

As discussed in Section 3.7, our model has likely underpredicted higher J line fluxes, especially for S(7)-S(9). Morphologically, our model also predicts smaller radial extent than observed for the higher J lines (Schwarz et al. 2025b; Pascucci et al. 2025). In this section, we examine whether these discrepancies could rule out a photoevaporative origin, or if they instead point to missing physical processes in the current model that might enhance extended high J emission.

These discrepancies can arise from simplifications in our treatment of the level populations. Specifically, we omit UV and X-ray pumping, as well as H2 excitation upon formation (hereafter formation pumping or chemical pumping)2, both of which can populate excited rovibrational levels. Another possible factor is our neglect of emission from the inner, hotter disk outside our computational domain that is scattered by dust at larger radii. We assess whether these processes could reconcile the discrepancies between our model and observations.

Regarding UV pumping, absorption in the Lyman and Werner bands (≳11.2 eV) excites H2 molecules to electronic excited states, followed by radiative decay into excited rovibra-tional levels of the electronic ground state. To assess whether UV pumping significantly enhances pure rotational level populations, we have performed one-zone level population calculations using the Paris-Durham code (Flower & Pineau des Forêts 2003; Godard et al. 2019), which can compute H2 level populations for given density, temperature, and UV field strength. We adopted physical conditions representative of the H2 wind near the dissociation front at r ~ 200 au, where our model appears to underpredict high J emission. Relevant parameters center around nH ~ 103 cm−3 (nH2 ~ 102−103 cm−3) and T ~ 600-900K.

We find that the impact of UV pumping on pure rotational excitation sensitively depends on the treatment of formation pumping, across a broad parameter space, nH = 1-104 cm−3, T = 500-2000 K, and G0 = 1-103. In the standard setup of the shock code, formation pumping follows a Boltzmann distribution at Tex = 17 249 K. Under this assumption, UV pumping has minimal effect on pure rotational levels, consistent with previous studies of irradiated interstellar gas (Black & van Dishoeck 1987; Godard et al. 2019) and protoplanetary disks (Nomura & Millar 2005; Nomura et al. 2007). Even for high J levels (J = 7-11), the enhancement from UV pumping is typically within a factor of two.

In contrast, if instead H2 is assumed to form only in the lowest levels ((v, J) = (0,0), (0,1)), corresponding to level population calculations in this study, UV pumping becomes the sole channel for populating higher levels. This leads to order-of-magnitude increases in the populations of high J pure rotational levels, particularly for J ≳ 7-8, when G0 ≳ 10. Even at G0 = 1, significant increases are seen in low-temperature, low-density gas, where collisional excitation is inefficient.

These results suggest that formation pumping, alongside UV pumping, plays a critical role in setting high J populations, particularly for J ≳ 7-8. Incorporating these processes could improve agreement with the observed high J fluxes and morphologies, indicating that the discrepancies do not rule out a photoevaporative origin. A detailed treatment, however, lies beyond the scope of this work and will be addressed in future modeling efforts.

The strong enhancement of populations due to formation pumping contrasts with the case of vibrationally excited states, such as the lowest-J levels at v = 1, where UV pumping is typically more effective, even though their excitation energies are comparable to those of pure rotational levels at J ≈ 8. This highlights the importance of including UV pumping when modeling vibrationally excited lines, such as the v = 1-0 S(1) line at 2.12 μm, which is commonly used to trace winds (e.g., Gangi et al. 2020; Pascucci et al. 2025). This line has also been found to be spatially extended, similar to the pure rotational S(9) emission (Pascucci et al. 2025). More recently, Kalscheur et al. (2025) have proposed FUV fluorescent lines as additional wind tracers. Together, these findings reinforce the need to incorporate UV pumping for testing models.

Similar to UV pumping, X-ray absorption can also excite H2 to rovibrational levels. Energetic photoelectrons produced by X-ray ionization can collisionally excite ambient H2 into electronically excited states, which then decay into various rovibrational levels of the ground electronic state (Gredel & Dalgarno 1995). These photoelectrons can also directly excite the molecules vibrationally, as they lose energy through collisions. Nomura et al. (2007) modeled these effects, along with UV and chemical pumping, in a hydrostatic disk and found little enhancement in pure rotational level populations, possibly because chemical pumping dominates rovibrational excitation. Thus, the impact of X-ray pumping is expected to be similar to that of UV pumping.

As for the potential contribution of infrared line scattering on small dust in the wind, its effect on high J emission appears minor, although some uncertainty remains. Schwarz et al. (2025b) showed that the extended H2 emission in SY Cha lies well above the flat scattered-light surface imaged by SPHERE at 2.2 μm, suggesting that scattering is unlikely to be a major factor in this system. In Tau 042021, S(5)-S(8) emission appears spatially coincident with 5 μm dust emission (Arulanantham et al. 2024), whereas S(9) emission seems spatially offset from it (Pascucci et al. 2025). Overall, we expect the contribution of scattering to high J emission to be small. This would especially be the case for photoevaporative winds given the generally dust-optically thin nature.

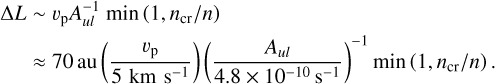

4.3 Stellar parameter dependence

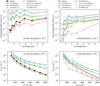

The properties of photoevaporative winds are generally sensitive to stellar UV and X-ray luminosities, which can strongly influence H2 emission. Here, we explore how varying these luminosities affects the morphologies and fluxes of the H2 lines, relative to our fiducial model. We also briefly consider the role of stellar mass. These tests provide context for our comparison with the observations in Section 4.4. They also highlight the potential of using correlations between H2 emission and stellar properties as a diagnostic of photoevaporation.

As LFUV increases, line emission is expected to strengthen due to enhanced heating. However, H2 also becomes more susceptible to FUV photodissociation, particularly in low-density, high-temperature regions (T ≳ 500 K), making the net effect on the fluxes nontrivial. Additionally, higher LFUV broadens the H2 dissociation front, increasing the semi-opening angle.

To assess this, we restarted the fiducial simulation with higher FUV luminosities, LFUV = 4.0 × 1030 erg s−1 and 3.5 × 1031 erg s−1 (4 times and 40 times the fiducial value), corresponding to Ṁacc = 10−9 M⊙ yr−1 and 10−8 M⊙ yr−1, respectively. All other parameters remained the same as in Table 1. In these runs, FUV photodissociation contributes to H2 destruction at levels exceeding or comparable to those from X-ray photoionization in the fiducial model.

In the four times FUV case, the overall disk structure is similar to the fiducial model (Figure 2), but enhanced FUV photodissociation destroys hot H2 near the dissociation front, reducing the vertical extent of high J emission, and slightly broadening the semi-opening angles to θ̄open ≈ 40°-46°. Line fluxes decrease by a factor of a few (compare yellow and black lines in the top panels of Figure 13). The energy efficiency is also correspondingly reduced to LH2 ≈ 0.93 × 10−3LUVX.

These trends are more pronounced in the 40 times FUV run. X-ray heating remains dominant throughout most of the H2 region, except near the wind base where FUV photoelectric heating becomes comparable. The main effect of stronger FUV is enhanced destruction of warm H2 (T ≳ 300 K). The overall temperature structure changes little but is slightly reduced due to increased cooling by O I, whose abundance rises following stronger CO photodissociation. These effects collectively lead to weaker H2 line fluxes (pink lines in the top panels of Figure 13). When disk obscuration is included for an edge-on geometry (pink line in the top right panel), the depletion of warm H2 further reduces fluxes from the extended H2 winds. The resulting energy efficiency is even lower at LH2 ≈ 1.3 × 10−4LUVX.

We also tested enhanced X-ray luminosities of LX = 2.82 × 1031 erg s−1 and LX = 2.82 × 1032 erg s−1 (10 times and 100 times the fiducial value; the latter for experimental purposes). At ten times the fiducial value, line fluxes increase across all transitions (thick green lines in Figure 13), and the semi-opening angles widen to θ̄open ≈ 45°-55°. High J emission remains compact, leaving unresolved the issue discussed in Section 4.2. At 100 times, fluxes rise further (thick blue lines in Figure 13) and opening angles reach θopen ≈ 50°-60°. These trends reflect faster H2 destruction and more efficient heating of denser H2 layers at higher LX. The energy efficiency is comparable to the fiducial model: LH2 = 5.2 × 10−3LUVX and 4.8 × 10−3LUVX for the 10 times and 100 times runs, respectively. The relatively higher efficiencies, compared to the high LFUV models, indicate greater energy deposition per H2 molecule destruction.

In summary, both H2 morphology and fluxes are sensitive to UV and X-ray luminosities. Our preliminary results reveal overall trends: line fluxes increase with higher LX and lower LFUV, while semi-opening angles grow with both. However, the decreasing trend of high J line fluxes (e.g., S(5)-S(9)) with increasing LFUV is uncertain - if UV and chemical pumping were included, higher LFUV could instead enhance high J emission. Moreover, the results from the high FUV runs should not be interpreted as implying that H2 winds cannot be reproduced in systems with strong FUV radiation, as variations in PAH and elemental abundances may also play a role (Section 4.5). These results simply illustrate relative trends when either the FUV or X-ray luminosity is held fixed. A systematic parameter study is therefore needed to verify these trends and fully map the range of fluxes and morphologies that photoevaporative winds can produce. Our current findings suggest that photoevaporative H2 winds are more readily detectable in evolved disks around low-mass, active stars with low accretion rates (particularly in low J lines).

Stellar mass can also influence wind geometry. For instance, stars with M* < 1 M⊙ may produce narrower semi-opening angles than our fiducial model, as H2 can be launched from smaller radii and the disk scale height increases due to weaker stellar gravity. This trend contrasts with the broader semiopening angles seen under stronger UV and X-ray irradiation, suggesting that different combinations of M*, LX, and LFUV could result in similar wind morphologies.

To test this, we ran a model with M* = 0.4 M⊙ and ten times the fiducial X-ray luminosity (with L* = 0.93 L⊙ and R* = 2.12R⊙). We chose this setup, as it is expected to most closely reproduce the morphology in the fiducial model, based on the preceding exploration. Indeed, this model yields a similar morphology to the fiducial run (see also the discussion in Section 4.4.1). The H2 line fluxes are comparable to those in the ten times X-ray run (see the light green lines in the top panels of Figure 13).

These preliminary findings reinforce our argument in Section 4.1 that, without well-constrained stellar properties, geometric structure alone is insufficient to distinguish between photoevaporation and MHD winds. A systematic exploration of both stellar mass and luminosities is therefore essential for robust interpretation. On the theoretical side, these variations of morphology and fluxes indicates the need of source-specific modeling in conclusively assessing the origin of observed H2 winds.

4.4 Comparisons with JWST observations

The characteristic X-shaped morphology of the H2 emission in our model images (Figure 5) resembles recent JWST observations of Tau 042021 (Arulanantham et al. 2024) and SY Cha (Schwarz et al. 2025b), prompting the question of how well our photoevaporation model can quantitatively reproduce these features. In this section, we address that question. Comparisons with Tau 042021 (Arulanantham et al. 2024) and SY Cha (Schwarz et al. 2025b) are presented in Sections 4.4.1 and 4.4.2, respectively.

4.4.1 Tau 042021

Tau 042021 (2MASS J04202144+2813491) features an edge-on disk around an M-type star in Taurus (Luhman et al. 2009; Stapelfeldt et al. 2014; Simon et al. 2019). The disk inclination is i > 85° (Villenave et al. 2020), and the stellar mass is M* = 0.4 M⊙ (Duchêne et al. 2024)3. The accretion rate is estimated at Ṁacc = 2 × 10−11 M⊙ through hydrogen recombination lines (Arulanantham et al. 2024), though this likely underestimates the true value due to the nearly edge-on orientation. In fact, Bajaj et al. (2025) report a much higher accretion rate Ṁacc ~ 10−8 M⊙ yr−1 based on jet mass-loss rates.

Recent ALMA observations in Bands 4 and 7 have resolved the disk’s vertical structure, revealing strong settling of large grains (Villenave et al. 2020). Meanwhile, JWST/MIRI imaging at 7.7 μm and 12.8 μm has revealed a prominent X-shaped structure extending above the midplane (Duchêne et al. 2024). This X-shaped emission lies above the warm molecular 12CO layer traced by ALMA, which has a semi-opening angle of θ̄open ~ 55° and vertical extent reaching up to ~225 au.

More recently, Arulanantham et al. (2024) detected the H2 S(1)-S(8) lines with JWST/MIRI. The S(2) image (12.3 μm) exhibits a clear X-shaped morphology, consistent with earlier 7.7 μm and 12.8 μm data of Duchêne et al. (2024), and may in part be traced by vertically extended 12CO (Foucher et al. 2025). The S(1)-S(4) lines are similarly vertically extended beyond the scattered-light continuum, whereas S(5)-S(8) appear more compact and cospatial with dust emission at 5 μm.

The semi-opening angle from the S(2) line is θ̄open = 35° ± 5°, which Arulanantham et al. (2024) interpret as evidence of a MHD wind. They cite its consistency with the i ~ 35° inclination angle, at which the largest blueshifts of [O I] BCs and NCs are observed (Banzatti et al. 2019; Pascucci et al. 2023) The BCs, in particular, are considered to originate from MHD winds based on their inferred emitting radii. This inclination is also consistent with the picture of the “bead on a rigid wire” MHD wind model, which requires θ > 30° to launch outflows (e.g., Blandford & Payne 1982). However, this interpretation remains tentative, as neither the launching radius nor velocity structure can be resolved with MIRI’s channel 3 pixel scale (0.″245 ~ 34 au) or spectral resolution (∆v ~ 120 km s−1 at 12 μm).

Pascucci et al. (2025) also favors the MHD wind scenario based on the observed wind morphologies and nested structures. The view also aligns with the presence of the narrow, collimated jet traced by [Fe II] and the recently reported high accretion Ṁacc ~ 10−8 M⊙ yr−1 (Bajaj et al. 2θ25), which may lead to significant shielding of stellar UV and X-ray by inner winds, potentially making photoevaporation less efficient (Pascucci et al. 2020; Takasao et al. 2022).

Nevertheless, the observed H2 line centroids lie between −20-2 km s−1 (Arulanantham et al. 2024), a possible range of photoevaporative winds - though velocities along the rotational axis is not measurable in edge-on systems. In addition, the total luminosity of the pure rotational lines (Table 2) is LH2 ≈ 1.6 × 1028 erg s−1, consistent with expectations for pho-toevaporative winds driven with UV and X-ray luminosities of ~1030−1031 erg s−1 (Section 3.2 and Eq. (2)). From these perspectives, a photoevaporative origin can remain a viable possibility, and merits comparison with our model predictions to assess its plausibility.

Figure 14 compares our convolved S(2) maps with the observed image from Arulanantham et al. (2024). The fiducial model reproduces the observed morphology well, with a semiopening angle of θopen = 36.1° (Table 3), consistent with the reported 35° ± 5°. A similar agreement is seen for the S(9) line (θopen = 37°), consistent with ~35°-40° measured from PSF-deconvolved JWST/NIRSpec images (Pascucci et al. 2025). The geometric radius Rgeo is somewhat larger in our model (≈ 19-26 au vs. 6 ± 7 au), but still broadly consistent. Since our fiducial model assumes a higher stellar mass (M* = 1 M⊙ vs. M* = 0.4 M⊙ for Tau 042021), larger wind-launching radii and Rgeo are expected owing to the greater critical radius Rcrit (Liffman 2003). For molecular gas at ≈103K, Rcrit ~ 36 au, giving Rgeo ~ 0.5-0.7Rcrit in our model; the corresponding Rcrit ~ 14 au for Tau 042021 implies Rgeo ~ 7-10 au, in closer agreement with the observed value.

Despite the morphological agreement, the fiducial model is fainter than the observations. This may appear inconsistent with Figure 7 and Table 2, which show broadly consistent low J line fluxes, but this discrepancy arises mainly because the observed fluxes are measured over smaller emitting areas (see the green contour in the left panel of Figure 14). The observed flux (≈7.8 × 10−16 erg s−1 cm−2) is measured within this contour, whereas the model flux (≈2.0 × 10−16 erg s−1 cm−2) is integrated over the full domain. When limited to the region where the surface brightness exceeds 35% of the peak (the first dashed cyan contour), the model flux becomes 1.3 × 10−16 erg s−1 cm−2, about six times less than the observed value.