| Issue |

A&A

Volume 706, February 2026

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A144 | |

| Number of page(s) | 21 | |

| Section | Catalogs and data | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202449408 | |

| Published online | 09 February 2026 | |

The SRG/eROSITA all-sky survey: Hard X-ray selected active galactic nuclei

1

Max-Planck-Institut für extraterrestrische Physik,

Giessenbachstrasse 1,

85748

Garching,

Germany

2

Department of Astronomy, University of Geneva,

Ch. d’Ecogia 16,

1290

Versoix,

Switzerland

3

Exzellenzcluster ORIGINS,

Boltzmannstr. 2,

85748

Garching,

Germany

4

Max-Planck Institut für Astronomie,

Königstuhl 17,

69177

Heidelberg,

Germany

5

Dipartimento di Fisica e Astronomia “Augusto Righi”, Alma Mater Studiorum Università di Bologna,

via Gobetti 93/2,

40129

Bologna,

Italy

6

INAF-Osservatorio di Astrofisica e Scienza dello Spazio di Bologna,

via Gobetti 93/3,

40129

Bologna,

Italy

★ Corresponding author: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

30

January

2024

Accepted:

13

January

2025

Context. The eROSITA instrument on board the Spectrum Roentgen Gamma (SRG) satellite performed its first all-sky survey between December 2019 and June 2020. This paper presents the resulting hard X-ray (2.3–5 keV) sample, the first created from an all-sky imaging survey in this energy range, for sources within the western galactic sky (eROSITA-DE).

Aims. We produced a large uniform sample of hard-X-ray selected active galactic nuclei (AGN), and characterised them with supporting multi-wavelength astrometry, photometry, and spectroscopy. For the 2863 sources within the sky coverage of the DESI imaging Legacy Survey Data Release 10 (LS10; >15 000 deg2), counterparts were identified and classified. We also performed comparisons with the Swift BAT sample and HEAO-1 AGN sample to attempt to better understand the effectiveness and sensitivity of eROSITA in the hard band.

Methods. The 5466 hard X-ray selected sources detected with eROSITA are presented and discussed here. The Bayesian statistics-based code NWAY was used to identify the counterparts for the X-ray sources. These sources were classified based on their multi-wavelength properties, and the literature was searched to identify spectroscopic redshifts, which further inform the source classification. A total of 2547 sources were found to have good-quality counterparts, and 111 of these have been detected only in the hard band. The median redshift of the extragalactic sources is ~0.19.

Results. Compared with other hard X-ray selected surveys, the eROSITA hard sample covers a larger redshift range and probes dimmer sources, providing a complementary and expanded sample as compared to Swift BAT. Examining the column density distribution of missed and detected eROSITA sources present in the follow-up catalogue of Swift BAT 70 month sources, it is demonstrated that eROSITA can detect obscured sources with column densities >1023 cm−2 corresponding to ~14% of the full sample, but that the completeness drops rapidly thereafter. A sample of hard-only sources, many of which are likely to be obscured AGN with column densities ~1023 cm−2, is also presented and discussed. We caution that a large number of hard-only sources are believed to be spurious, based on simulations, and that additional cuts on counterpart quality or requiring spectroscopic redshifts should be applied to use this sample. X-ray spectral fitting reveals that these sources have extremely faint soft X-ray emission and their optical images suggest that they are found in more edge-on galaxies with lower b/a.

Conclusions. The first eROSITA all-sky survey provided the first imaging survey above 2 keV, and the resulting X-ray catalogue has been demonstrated to be a powerful tool for understanding AGN, in particular the heavily obscured AGN found in the hard-only sample.

Key words: galaxies: active / quasars: general / galaxies: Seyfert

© The Authors 2026

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model.

Open Access funding provided by Max Planck Society.

1 Introduction

The primary science driver of eROSITA (extended Roentgen Survey with an Imaging Telescope Array; Merloni et al. 2024) on board the Spectrum Roentgen Gamma (SRG) (SRG; Sunyaev et al. 2021) mission is to detect X-ray emission from ~105 clusters of galaxies, enabling X-ray mapping of the largescale structure of the Universe (Merloni et al. 2012; Predehl et al. 2021). However, by far the most prevalent sources of X-ray emission detected by eROSITA originate in active galactic nuclei (AGN), driven by powerful supermassive black holes which are actively accreting material (see for example, Salvato et al. 2022; Nandra et al. 2025). AGN emit across all wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation, from radio to X-ray and γ-rays, and may even outshine their host galaxies (see e.g. Padovani et al. 2017, for a review). By studying these sources in the X-rays, these effects may be investigated as the X-ray emission originates closest to the supermassive black hole (see e.g. Elvis et al. 1978). The primary source of these X-rays is thought to be the corona (e.g. Haardt & Maraschi 1991, 1993; Merloni et al. 2000; Fabian et al. 2004), a population of relativistic electrons which Compton up-scatters UV photons from the accretion disc. The result is an X-ray spectrum that takes the approximate form of a power law, with a low-energy turn-around of ~1 eV (Shakura & Sunyaev 1973) corresponding to the temperature of the UV photons in the inner accretion disc, and a high-energy turn-over at 100–300 keV (e.g. Petrucci et al. 2001; Fabian et al. 2015; Tortosa et al. 2018; Middei et al. 2019) corresponding to the electron temperature in the corona.

The AGN unification model (Antonucci 1993; Urry & Padovani 1995) explains the observed differences in the observed properties as changes in the viewing angle (Seyfert 1943; Khachikian & Weedman 1974; Osterbrock & Pogge 1985); Seyfert 1 (type 1) AGN are viewed face-on, appearing as unobscured and revealing broad optical spectral lines and typically showing strong soft X-ray emission, while Seyfert 2 (type 2) AGN are viewed edge-on, obscured by a cold dusty distribution of clouds referred to as the torus. The optical spectra therefore do not show evidence of broad lines, and often the X-ray spectra reveal weakened soft X-ray emission due to obscuration with column densities of the order of NH > 1022 cm−2 (Merloni et al. 2014; Burtscher et al. 2016). When the absorbing column density is sufficiently high (~1022.5–23 cm−2), the source lacks observable soft X-rays, only revealed at energies above ~2 keV. When the column density exceeds the inverse of the Thomson cross-section (![$\[\sigma_{T}^{-1} \simeq 1.5 \times 10^{24}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa49408-24/aa49408-24-eq1.png) cm−2), the source is defined as Compton thick, and the coronal emission is largely obscured below 10 keV (e.g. Comastri 2004). Given that a large fraction or even majority of AGN in the local Universe are believed to be obscured (e.g. Maiolino & Rieke 1995; Maiolino et al. 1998; Matt et al. 2000; Fiore et al. 2009), and that a correspondingly large portion of the accretion energy density of the Universe is believed to be contained in obscured AGN (e.g. Fabian 1999; Fabian & Iwasawa 1999; Aird et al. 2015; Buchner et al. 2015), detecting these sources is of particular importance.

cm−2), the source is defined as Compton thick, and the coronal emission is largely obscured below 10 keV (e.g. Comastri 2004). Given that a large fraction or even majority of AGN in the local Universe are believed to be obscured (e.g. Maiolino & Rieke 1995; Maiolino et al. 1998; Matt et al. 2000; Fiore et al. 2009), and that a correspondingly large portion of the accretion energy density of the Universe is believed to be contained in obscured AGN (e.g. Fabian 1999; Fabian & Iwasawa 1999; Aird et al. 2015; Buchner et al. 2015), detecting these sources is of particular importance.

Numerous surveys making use of X-ray telescopes with sensitivity above 2 keV have been conducted to detect obscured AGN. First, the non-imaging telescope HEAO-1 (Rothschild et al. 1979) surveyed the entire sky in the 0.2–25 keV band, creating the bright sample (>3 × 10−11 ergs s−1 cm−2) of hard X-ray AGN presented in Piccinotti et al. (1982), which have been re-examined in many later works. Later works used imaging telescopes covering smaller and/or non-contiguous areas of the sky; for example, using ASCA (Ueda et al. 1999), BeppoSAX (Della Ceca et al. 2008), Chandra (e.g. Nandra et al. 2015), and XMM-Newton (e.g. Fiore et al. 2003; Brusa et al. 2007; Cocchia et al. 2007; Hasinger et al. 2007). These missions are mostly sensitive below 10 keV; complementary higher-energy missions, including NuSTAR (3–79 keV; Harrison et al. 2013) and Swift BAT (14–195 keV; Gehrels et al. 2004), were employed to detected heavily obscured, Compton-thick AGN. Swift BAT performed an all-sky survey in the ultra-hard X-ray band, with the most recent 105 month release (Oh et al. 2018) detecting 1632 X-ray sources, including at least 1105 AGN. Many of these sources have been followed up with NuSTAR, whose improved energy sensitivity and softer X-ray coverage has enabled spectral modelling to compare torus models (Ikeda et al. 2009; Murphy & Yaqoob 2009; Brightman & Nandra 2011; Baloković et al. 2018, 2019; Buchner et al. 2019).

As a precursor to the all-sky surveys, the eROSITA Final Equatorial Depth Survey (eFEDS; Brunner et al. 2022) provided key insights into the science capabilites of eROSITA surveys. Before the eROSITA all-sky survey, eFEDS was at the time the largest contiguous dedicated X-ray imaging survey. eFEDS is designed to mimic the depth of the full planned, 8-pass, all-sky survey of eROSITA. From the 144 square degree survey, a small hard X-ray selected sample of 246 sources was identified. These sources are classified and analysed in Nandra et al. (2025) and Waddell et al. (2024), and in Brusa et al. (2022). From this analysis, a sample of 200 AGN were identified. It was found that the AGN covered a wide luminosity range, and had spectroscopic redshifts up to z ~ 3, with a peak in the distribution at z ~ 0.3, suggesting that we primarily selected a local sample of bright AGN. By selecting sources that did not appear to be present in the soft band (0.2–2.3 keV), a small sample of highly obscured AGN were recovered, with column densities up to logNH > 23. Other AGN, particularly some of the brighter sources at higher redshifts, were found to be blazars, which should be treated with care. Through spectral analysis, Waddell et al. (2024) also showed that many sources require additional spectral components beyond a simple obscured power law, including a warm absorber (e.g. George et al. 1998; Kaspi et al. 2000; Blustin et al. 2004, 2005; Gierliński & Done 2004; Mizumoto et al. 2019), a neutral partial covering absorber (e.g. Tanaka et al. 2004; Parker et al. 2021), or a soft excesses (e.g. Pravdo et al. 1981; Arnaud et al. 1985; Singh et al. 1985; Ross et al. 1999; Ross & Fabian 2005; Done et al. 2012; Petrucci et al. 2018, 2020; Waddell et al. 2024) to fully model the spectral complexity. The eFEDS hard sample thus illustrated potential for detailed AGN analysis with the full all-sky survey.

The first eROSITA all-sky survey (eRASS1; Merloni et al. 2024) hard X-ray selected sample is highly complementary to these works. Covering half the sky, the vast size of the survey has yielded a large sample of hard X-ray selected sources (Merloni et al. 2024). Although eROSITA lacks sensitivity above 8 keV, it is highly sensitive to soft X-ray emission, enabling accurate modelling of the obscuring column densities. Furthermore, with excellent soft X-ray spectral resolution, eROSITA spectra can be fit with physically motivated models to better understand the nature of X-ray emission and absorption components (Waddell et al. 2024). Selecting hard-X-ray detected sources that lack soft X-ray emission can also allow the identification of obscured AGN.

In this paper we present the counterparts, classifications, and an analysis of the X-ray and optical properties of the 5466 hard X-ray selected sources in the first all-sky survey. We focus on X-ray point sources that have not been flagged as potentially spurious or problematic, with a particular focus on the identification of AGN. In Sect. 2 we provide an expansion of the X-ray properties of the catalogue described in Merloni et al. (2024), and define a hard-only sample with no significant detection of emission below 2.3 keV. In Sect. 3 information on the counter-parts within the DESI imaging legacy surveys data release 10 (Dey et al. 2019) is described; spectroscopic redshifts are compiled, where available; sources are classified; and beamed AGN are flagged. In Sect. 4 we briefly describe AGN matched from outside the Legacy survey. Section 5 presents a comparison to the Swift BAT survey and Sect. 6 compares to the HEAO-1 AGN sample. Section 7 briefly discusses variable sources and, in particular, variable AGN. The spectroscopic AGN sample is presented in Sect. 8, with a particular focus on hard-only AGN. Further discussion is given in Sect. 9, and our conclusions are given in Sect. 10. Throughout this paper, we adopt a ΛCDM cosmology with ΩΛ = 0.7, Ωm = 0.3, and H0 = 70 km s−1 Mpc−1.

2 Properties of the eRASS1 hard sample

2.1 Population information

The hard (2.3–5 keV) X-ray selected catalogue from the eRASS1 all sky survey in the western galactic sky (eROSITA-DE) is presented in Merloni et al. (2024), and the X-ray positions of all sources are shown in Fig 1. Relevant additional subsamples are also shown in this plot, which are described in the following subsections.

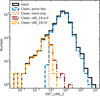

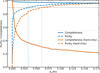

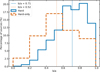

The catalogue contains a total of 5466 sources, with a hard-band detection likelihoods of DET_LIKE_3> 12, where band 3 is 2.3–5 keV (Merloni et al. 2024). Based on simulations performed in Seppi et al. (2022), this indicates a spurious fraction of 10% based on all-sky estimates, as can be seen from Fig. 2 (top). The background or spurious sources are shown in grey, the point-like simulated sources are shown as blue dashed lines, and extended simulated sources are shown as light blue dash-dotted lines. The spurious fraction is strongly dependent on the detection likelihood; it is around 10% at DET_LIKE_3=12, dropping to 2.5% around DET_LIKE_3 of 15, and nearly 0 at a DET_LIKE_3 of 18. For point-like sources, Fig. 2 (bottom) shows the same for hard-only sources; these are discussed further in Sect. 2.2.

Out of the 5466 sources, 5087 sources are considered to be point-like in the X-ray, having a EXT_LIKE (extended likelihood) of 0. The other 379 sources are candidate extended sources in the X-ray. These are discussed in more detail in Sect. 2.3.

A number of flags indicating spurious or otherwise problematic sources are presented in the catalogue, and are outlined in Table 5 of Merloni et al. (2024). These include five flags for potentially spurious sources, identified due to their proximity to supernova remnants (SNRs), bright point sources, stellar clusters, large local galaxies, known galaxy clusters, or sources potentially contaminated with optical loading. A further three flags identify sources for which no error bars were provided on the coordinate errors, extent errors, or source count errors. While these sources are not necessarily spurious, they are removed for analysis as these parameters are necessary for sample selection and counterpart identification, and cannot be trusted for flagged sources. When these flagged sources are removed, a total of 5020 sources remain, 4895 of which are point-like.

A key difference between the main and hard X-ray samples is the distribution of the positional uncertainty (at the 1σ level), contained in the column POS_ERR. These can be seen in Fig. 3, where sources in the main sample are shown in grey, all sources (including those flagged as spurious) in this hard sample are shown in black, non-flagged hard-only sources are shown in orange, and non-flagged sources in the hard sample with soft detections are shown in blue. The astrometric calibration (Merloni et al. 2024) imposes a lower bound of 0.9″ in the calculation of POS_ERR. In the main sample, the peak of the distribution is found at ~4.5″, whereas for the hard sample it is found around 1.5". This is related to the actual source detection algorithm employed by eROSITA, as described in Brunner et al. (2022); Nandra et al. (2025). The hard X-ray selected sample is compiled by running three simultaneous source detection runs; one in the 0.2–0.6 keV band, one in the 0.6–2.3 keV band, and one in the 2.3–5 keV band. The positional error is then derived using all three source detection bands. Therefore, sources which are detected in all three bands (e.g. those with both soft and hard X-ray emission) will have much lower positional errors, even compared to entries in the main catalogue (see Nandra et al. (2025) for further explanation). This also affects the counterpart identification procedure, since preference will be given to sources within the positional error.

There is also a difference observed for the hard-only sources; since their positions are only determined by the hard X-rays, the positional errors are larger and the distribution more closely follows that of the main sample. Many sources flagged as spurious also have large or absent positional errors, and are only presented in the black curve. By contrast, most of the sources with very small positional errors are real, bright sources with excellent positional accuracy. The reason the histogram drops off so quickly is that many sources have very small positional errors, so the peak of the distribution should be at or below the imposed minimum of 0.9″.

The distribution of X-ray counts and a comparison to the main sample can be found in Fig. 5 of Merloni et al. (2024). The distribution peaks at only ~7–8 counts in the hard band, but extends up to tens of thousands for the brightest sources. More detailed flux distributions are presented in Sect. 3 of this work.

|

Fig. 1 Hard X-ray detected sources in the first all-sky survey. The non-flagged point-like sources are shown as blue circles, and the non-flagged extended sources are shown as pale blue circles. The non-flagged point-like hard-only sources are shown as dark orange squares, and the hard-only extended sources are shown as light orange squares. Sources flagged as problematic are shown as grey triangles. The size of the shapes corresponds to the hard-band (2.3–5 keV) flux: larger shapes correspond to brighter X-ray fluxes. The values total 5466 sources. |

|

Fig. 2 Simulated detection fractions. Top: distribution of population fractions for simulated sources with respect to DET_LIKE_3. Simulated point sources are shown as a blue dashed line labelled PNT, simulated extended sources are shown as a light blue dash-dotted line labelled EXT, and spurious sources (e.g. not real sources in the simulations) are shown as a solid grey line labelled BKG. Bottom: distribution of population fractions for simulated hard-only sources with respect to DET_LIKE_3. Simulated point sources are shown in orange, and background sources are shown as a solid grey line labelled BKG. A solid black line at DET_LIKE_3 of 12 is shown in both panels to indicate our significant detection threshold. |

|

Fig. 3 Distribution of errors on the coordinates (POS_ERR) for individual sources. The eRASS1 main sample is shown as a grey dash-dotted line. The hard sample is shown as a black solid line, and is further subdivided into non-flagged point-like hard sources, and point-like hard-only sources, and are shown as a blue dashed line and an orange dotted line, respectively. Median values are indicated as vertical lines in corresponding colours. |

2.2 Hard-only sources

In this work, hard-only sources are defined as those having

![$\[\text { DET_LIKE_1 }<5 ~\& \text { DET_LIKE_2 }<5,\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa49408-24/aa49408-24-eq2.png) (1)

(1)

where 1 indicates the 0.2–0.6 keV band and 2 indicates the 0.6–2.3 keV band. In this way the detection likelihood in neither band is equal to the supplementary sample cut-off, at DET_LIKE_0>5 (where 0 indicates the 0.2–2.3 keV band). In total, 738 sources meet this criteria. These sources are distributed across the sky, with many being in or near the galactic plane, as these X-ray sources would be obscured by the Milky Way disc. They have higher positional errors than other sources in the hard sample, complicating counterpart identification. There is also a higher expected spurious fraction among the hard-only sample, as shown in Fig. 2 (bottom), closer to 65% at DET_LIKE_3 of 12, but falling off to about 30% at a DET_LIKE_3 of 15 and to 0 above a DET_LIKE_3 of 17. This would imply that ~480/738 hard-only sources are spurious, leaving ~260 which are expected to be real astrophysical sources. Stricter cuts could also be made on DET_LIKE_3 in order to select a purer, but possibly less complete, sample. Identifying these is of particular interest, as these are important objects for future study.

Figure 4 shows the distribution of DET_LIKE_3, the detection likelihood in the hard band. In general, the hard-only sources have lower DET_LIKE_3 values; this is sensible, as eROSITA is extremely sensitive in the soft band and should easily be able to detect soft X-ray emission, if present; so any hard-only sources must be very dim and/or heavily obscured.

Examining only the point-like hard-only sources, there are 684 meeting the above definition (Eq. (1)). Our definition differs from that which is presented in Merloni et al. (2024), which relies on spatial coincidence of sources in the main and hard catalogues (weak match) and a ratio of their counts (strong match). Sources which are weak matches have a negative value in the UID_1B column in the hard X-ray catalogue, and those no matches have a 0 in the UID_1B column. Selecting the point-like sources, 729 have no matches, and 752 have no or weak matches. However, examining the distribution of fluxes and detection likelihoods in band 2 (0.6–2.3 keV; see Fig. 5), there are some sources with high detection likelihoods of tens to thousands. These sources are extremely unlikely to be true, hard-only sources. By using the modified definition of Eq. (1), all of these sources are removed. Out of the 684 hard-only sources from this work, 673 are also hard-only using the definition in Merloni et al. (2024), demonstrating very large overlap between the two selections.

Also of interest are the sources for which the softest band has a significant detection likelihood, but the median band does not; that is, having DET_LIKE_1 < 5 & DET_LIKE_2 < 5. There are five such sources, all with DET_LIKE_1 < 9. Four of these sources are in the LS10 area, and none have any flags in the X-ray. Such sources may be candidates for obscured AGN, with significant soft X-ray leakage due to Compton scattering or an ionised absorption medium.

|

Fig. 4 Distribution of DET_LIKE_3 (2.3–5 keV) values. The hard sample is shown as a black solid line, and is further subdivided into point-like sources and point-like hard-only sources (blue dashed line and orange dotted line, respectively). |

|

Fig. 5 Distribution of DET_LIKE_2 (0.6–2.3 keV) values. The hard sample is shown as a black solid line, and is further subdivided into non-flagged point-like hard sources and point-like hard-only sources (blue dashed line and orange dotted line, respectively). The hard-only samples as defined in Merloni et al. (2024) are also shown: the higher-fidelity, UID_1B=0 sample (pale orange dashed line) and the less pure UID_1B≤0 sample (dark red dash-dotted line). |

2.3 Extended sources

There are a total of 379 sources in the hard extended sample, peaking at an extent likelihood of EXT_LIKE ~140–150. This is very different from the extent likelihood distribution of the main sample, which peaks at EXT_LIKE ~3–4. This is because the hard sample primarily selects the brightest sources in the eROSITA X-ray sky, facilitating the identification of the sources type. Of the 379 sources, many are flagged as lying near a known cluster or SNR, and are thus likely spurious. Removing these, a total of 125 sources remain. Of these, 16 have been identified as being hard-only sources which satisfy Eq. (1). All but one of the remaining sources are found in the main catalogue and are described in Bulbul et al. (2024) and Kluge et al. (2024). Of the 16 hard-only extended sources, one is positionally coincident with a source in the main catalogue, and only three have sufficiently high extent likelihoods (EXT_LIKE > 9) to make it into the secure cluster catalogue Bulbul et al. (2024). Two sources are in the galactic plane, and the remaining source is spatially coincident with a known galaxy, LEDA 483209. It is therefore likely that, aside from LEDA 483209, these sources are spurious rather than being true heavily obscured clusters. For the remainder of this work, the focus is restricted to the 5087 point-like X-ray sources.

3 Counterparts in the legacy survey footprint

3.1 Counterpart identification

To attempt to identify the counterparts of the eRASS1 Hard sample, the photometric and other data provided in the DESI imaging legacy surveys, specifically the Legacy Survey Data Release 10 (LS10; Dey et al. 2019) were used. In addition to g-, r-, i-, and z-band photometry, LS10 also includes WISE fluxes, obtained from forced-flux photometry on the unWISE data at the positions of the Legacy Survey optical positions. LS10 is the first of the Legacy Survey data releases to include i-band photometry, and coverage is improved in the Southern Hemisphere, coincident with a large portion of the eROSITA-DE sky. In all, 15 342 deg2 of the sky are covered by at least one pass in all four photometry bands. This is defined using a multi-order coverage map (MOC), and is the sky area covered by all those 0.25×0.25 deg legacy survey ‘bricks’ which have at least 1000 detections, and which have estimated 5 sigma point-source depths of at least g<23.5, r<23.3, i<22.8 and z<22.3, in AB magnitudes. Of the 4895 X-ray point-like sources without flags, 2863 are in the legacy survey area, defined as having coverage in all four photometric bands. Out of these, 363 are hard-only sources in the LS10 area. These numbers and other key values of interest are listed in Table 1.

Counterpart identification is done using NWAY (Salvato et al. 2018, 2022), a Bayesian framework which has been specifically designed to identify counterparts for astronomical sources. This method uses positional information, positional errors, and the local X-ray source density as well as the multi-wavelength properties to assess the likelihood of an optical source being an X-ray emitter as well as being the correct counterpart. The training is performed on a 4XMM sample cut at a 0.5–2 keV flux of 2 × 10−15 ergs s−1 cm−2, which corresponds to the minimum flux of the hard sample. More details of the training are described in Salvato et al. (2022, Salvato et al., in prep.), in which the same method and training priors are applied to the main eRASS1 catalogue. Some caveats to this are discussed in Sect. 9.1.

Starting from the full hard X-ray catalogue, the extended sources are removed. NWAY is then run on the sample to find the X-ray counterparts. LS10 sources within a 60 arcsecond radius of the X-ray source are considered, in order to account for the few X-ray sources with very large positional error (maximum ~50 arcseconds), some of which are hard-only sources which are of particular interest in this work. Out of the 2863 point-like, non-problematic X-ray sources in the LS10 area, 2850 sources have a primary counterpart (match_flag=1).

Useful reference numbers for the different samples used throughout this work.

3.2 Sources without a counterpart

Since 2850 out of 2863 sources have at least one counterpart, this leaves a mere 13 sources without a LS10 counterpart. These sources are listed in Table 2. To attempt to identify these sources, we examine the sky in the legacy survey viewer tool1, and query their positions in NED and in SIMBAD (Wenger et al. 2000) using a two arc minute match radius. This extremely large search radius allows us to check if there are any known sources in the general area of the X-ray detections, but this is not used to assign counterparts. Notes on the results of these searches can be found in the far right column of Table 2.

In total, three sources are clearly associated with bright AGN which may have issues with their photometry in LS10, one source is coincident with a bright star, one source is coincident with a cluster of galaxies, one source appears in a gap in LS10 which is not reflected in the MOC, and one source has no previously named nearby sources. A further six sources are all found in the South Ecliptic Pole (SEP) area (Merloni et al. 2024). There are issues with the shallow depth or missing photometric bands in LS10 in this area, as well as issues with source confusion given the very high density of X-ray sources in this area due to the repeated exposures in this area. The repeated exposures also mean that lower flux sources are probed. Therefore, it is reasonable that some sources are missing counterparts there. The DET_LIKE_3 values are high for most sources, so it is likely that most are real X-ray sources.

3.3 Calibration of p_any thresholds

In order to assess the quality of the counterpart match, the p_any values produced by NWAY are used. For each entry in the X-ray catalogue, the p_any is defined as the probability that there is a counterpart. To assign thresholds to these values, a new X-ray catalogue is produced, where the RA and Dec of the X-ray sources have each been shifted by two arcminutes. Sources at these new shifted positions which are coincident with an original X-ray source are then removed. In this way, it is possible to evaluate the incidence of chance alignment in the NWAY cross-matching procedure by comparing the p_any distributions of real and spurious matches.

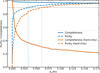

The (normalised) distributions of the p_any values obtained from the real and shifted samples are shown in Fig. 6. Only point sources with no flags in the X-ray are considered. For the shifted sources, only a very small minority of sources have large p_any, showing that NWAY rarely finds a secure counterpart where none should be found. There is a very high peak at ~0, with most sources having very low p_any values. In contrast, the p_any values of the real sources are more broadly distributed, with the largest peak at a p_any of 1.

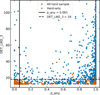

To define a desirable p_any threshold to use to define a secure counterpart, purity and completeness curves are constructed. The completeness is defined as the fraction of sources which have a real p_any greater than a specified value, whereas purity is defined as the fraction of spurious sources which have p_any greater than a given threshold. These are shown in Fig. 7, with, the hard-only sources shown in orange, and the sources which also have soft detections (e.g. those which are not hard-only) are shown in blue. Completeness curves are shown as solid lines, and purity curves are shown with dashed lines. To achieve a purity of 90%, a threshold of p_any > 0.033 should be used for the hard sample, and p_any > 0.061 for the hard-only sample, indicated with horizontal lines in corresponding colours. The hard sample has a completeness of ~98% at this purity, and the hard-only sample has a much lower completeness of ~30%. We note that this is consistent with the much higher expected spurious fraction of the hard-only sample, where up to 65% of sources were expected to be spurious (see Sect. 2.2).

The dependence on the counterpart quality as a function of detection likelihood (DET_LIKE_3) is shown in Fig. 8, and we include hard-only sources in all curves provided they meet the detection thresholds. Three different thresholds are shown: for DET_LIKE_3>12, 10% of X-ray detected sources are expected to be spurious; for DET_LIKE_3>15, 2.5% of X-ray detected sources are expected to be spurious, and for DET_LIKE_3>18, <<1% of X-ray detected sources are expected to be spurious (see Seppi et al. 2022; Merloni et al. 2024, Sect. 2.1). The purity and threshold curves are much higher when these higher DET_LIKE_3 cuts are applied. These cuts also effectively remove all the hard-only sources, which typically have lower DET_LIKE_3 (e.g. Fig. 4). A highly pure, complete and very securely associated sample could be selected using higher DET_LIKE_3 and p_any cuts.

The p_any values with respect to the DET_LIKE_3 values for the hard-only (orange squares) sources are shown in Fig. 9, alongside the full sample of sources with counterparts. A DET_LIKE_3 of 18 is indicated with a black solid line, above which X-ray detections have a very low (much less than 1%) chance of being spurious. A p_any of 0.061 is also shown with a black dashed line, which indicates the 90% purity cut on p_any for the hard-only sources. Predictably, many of the low DET_LIKE_3 sources also have low p_any, probably because many are spurious. Most sources with DET_LIKE_3 larger than 18 have secure counterparts. Of those which do not, a majority are located in the SEP, where both X-ray and LS10 counterparts are problematic due to the patchy coverage and low depth of the LS10 survey and the potential source confusion and dim fluxes probed in X-rays, and as such the results should probably not be trusted (see Liu et al., in prep.).

Applying these findings, we apply the 90% purity cuts to our samples, meaning that 10% of sources are spurious associations between X-ray and optical counterparts. Therefore, we define sources with a good counterpart as having p_any>0.033, and hard-only sources with good counterparts as having p_any>0.061, selecting a total of 2547 sources (of which 111 are hard-only sources) with good counterparts. These definitions are used in the following sections.

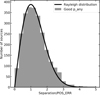

If the errors on the X-ray coordinates and the matching algorithm are accurate, then the angular separations of the LS10 counterparts from their eROSITA X-ray counterparts, normalised by the position errors, is expected to be modelled by a Rayleigh distribution. This is tested in Fig. 10, and the true distribution is in close agreement with the Rayleigh distribution.

Non-flagged point sources without counterparts in LS10.

|

Fig. 6 Distribution of p_any thresholds for the real (black solid line) and shifted (grey dotted line) samples. |

|

Fig. 7 Purity and completeness as a function of p_any values, defined as in Salvato et al. (2022). Purity and completeness for the sample with soft X-ray detections are shown as blue solid and dashed lines, respectively. Purity and completeness for the hard-only sample are shown as orange solid and dashed lines, respectively. The horizontal grey line shows a purity of 0.9, and the vertical dotted lines in corresponding colours indicate the p_any values for the 90% purity cuts. |

|

Fig. 8 Purity (dashed lines) and completeness (solid lines) as a function of p_any values, defined as in Salvato et al. (2022). The black, green, and pink lines show subsamples of sources with DET_LIKE_3>12, DET_LIKE_3>15, and DET_LIKE_3>18, respectively. |

|

Fig. 9 Distribution of DET_LIKE_3 values as a function of p_any, shown for both the hard-only sample (orange) and the remainder of the hard sample (blue). The vertical black line indicates the 90% purity cut on p_any for the hard-only sample and the horizontal dashed line shows a high-fidelity cut of DET_LIKE_3>18. |

|

Fig. 10 Distribution of separations between the optical and X-ray positions, divided by the X-ray positional errors. The sources with good p_any are shown in grey, and the expected Rayleigh distribution is shown as a solid black curve. |

3.4 Spectroscopic redshifts

Following the method of Ider Chitham et al. (2020), a compilation of spectroscopic redshifts was constructed from a large variety of literature sources. The specific paper queries can be found in the catalogue released with this work. Specific catalogues, queries and selection criteria are further described in Appendix D of Kluge et al. (2024).

The catalogue includes the RA and Dec taken from the Legacy Survey sources, which are matched within one arcsecond to the counterpart LS10 positions. The separations are typically less than 0.3 arcseconds, suggesting that the spec-z are indeed being reported for the LS10 sources associated to the X-ray counterparts. In total, 711 sources with good p_any have a spec-z which is available in this catalogue, 706 of which have z > 0.002 and can be considered extragalactic sources. Then, to further increase the number of spec-z available, we also match our optical counterparts to the spec-z in NED using a one arcsecond match radius. This match yields an additional 335 NED sources, 327 with extragalactic spec-z values of z > 0.002.

In addition to these spec-z values, we take advantage of the inclusion of the Gaia DR3 information in the LS10 catalogue to also include spec-z values from Quaia (Storey-Fisher et al. 2023), the publicly available Gaia–unWISE Quasar Catalog. In this work, spec-z are measured using the lowresolution Gaia spectrometer, and are improved using WISE selection criteria. The final sample has magnitudes G > 20.5 and shows good agreement with SDSS spec-z measurements (Storey-Fisher et al. 2023). Matching directly by Gaia DR3 ID and considering sources which do not have a spec-z from the compilation or NED, 505 sources with good p_any have a specz, all of which have z > 0.002 are can be considered extragalactic sources, as expected from a quasar catalogue. In total, this gives 1538 sources, including 23 hard-only sources, with a good counterpart and a spec-z of z > 0.002. The redshift distribution from each source, as well as the total distribution, is shown in Fig. 11.

Additionally, the agreement between the redshifts from the three catalogues used has been verified by computing the outlier fraction, where an extreme outlier is defined as

![$\[\left|z_2-z_1\right| /\left(1+z_1\right)>0.15,\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa49408-24/aa49408-24-eq3.png) (2)

(2)

where z1 is the better-constrained redshift and z2 is the lesserconstrained value. This definition is commonly used in order to assess the goodness of redshifts as well as to identify outliers, including catastrophic outliers (e.g. Salvato et al. 2009, 2011). A comparison of NED to the catalogue shows that the outlier fraction is very small, at 1.5%. A comparison of the spectroscopic redshift catalogue with Quaia shows that the outlier fraction is higher at ~17%. This is likely related to the low resolution of the Gaia spectrograph, and the apparent lack of sources in their low-redshift (z < 0.1) SDSS comparison sample. Some of these extreme outliers are removed when beamed sources removed (see description in Sect. 3.6, decreasing the outlier fraction to 13%). A majority of the outliers are at z > 0.3, so over interpretation of the higher-z sources is cautioned.

|

Fig. 11 Distributions of spectroscopic redshifts for the eROSITA hard sample. The hard sample is shown as a blue solid line, and the hard-only sample is shown as an orange filled histogram. Spec-z data from the spectroscopic redshift catalogue are shown as a black dash-dotted line, and NED spec-z data are shown as green dotted line. The Quaia redshifts are shown as pink dashed lines. |

3.5 Source classification

Learning from eFEDS, a similar source classification methodology is followed to Salvato et al. (2022). First, all sources which have a spectroscopic redshift of z > 0.002 are classified as extragalactic (1538 sources), while those with a spec-z of z < 0.002 are classified as Galactic. Additionally, sources which have a parallax which is significant at the >5σ level are classified as stars, selecting a total of 325 unique Galactic sources.

Where no spectroscopic redshift is available, or the parallax is not significant, the optical nature of the source is examined to see if it is extended. This is done by looking at the TYPE column in the LS10 catalogue. If the type is not equal to PSF, then the source is believed to be optically extended, and is thus likely to be a (nearby) galaxy. This allows us to classify 660 sources as likely extragalactic. Approximately 50% of the spectroscopic extragalactic sample is optically extended, while none of the Galactic sources are, further justifying this classification.

For remaining sources (339) without a spec-z, significant parallax, and which are not flagged as optically extended, we apply similar colour-colour cuts to Salvato et al. (2022). The relevant colour-colour plots are shown in Fig. 12, with different subsamples indicated with different colours and symbols, and equations used for cuts are listed in the legend. Only sources with type PSF in LS10 and sources where the signal-to-noise ratio >3 in all photometry bands are plotted.

The top left panel of Fig. 12 shows the z − W1 and g − r colours for the hard sample. The line of separation has the same slope as prescribed by Salvato et al. (2022), but with an intercept of −0.2, rather than −1.2 reported in that work. This is because Salvato et al. (2022) included many local galaxies and clusters in this diagnostic, which are removed in this work by selecting only point-like sources in the X-ray and optical. We investigate the three outliers with large z − w1 values; two are located <10″ from known stars (V* HQ Eri and G 41-14B), and one is ~5″ from a known galaxy NGC 1097 at a redshift of 0.004, and all have low or intermediate p_any values, suggesting that there may be issues with the counterparts for these sources. Despite these outliers, the new selection is very pure, with 99% of spectroscopic extragalactic sources lying in the upper region of the plot. The W1 versus soft X-ray diagnostic from Salvato et al. (2022) shown in the right-hand corner of Fig. 12 are similarly pure. Here, the soft X-ray flux is computed using the hard X-ray flux which is available even for the hard-only sources, extrapolated using an absorbed power law with a photon index of 1.9 (e.g. Liu et al. 2022; Waddell et al. 2024; Nandra et al. 2025) and a column density of 4 × 1020 cm−2. We caution that these values are only rough estimates of the intrinsic soft X-ray flux for the hard-only sources, and suggest against over-interpreting the classification of hard-only sources without spectroscopic redshifts. We note however that this approach is likely sufficient for the comparison of X-ray faint stars versus AGN, which is the primary objective of this diagnostic plot.

The bottom left corner of Fig. 12 combines the two top figures to create the final source classification. Sources which have both colours >0 are classified as having extragalactic colours and plotted as unfilled, dark purple diamonds, and those with either colour <0 are classified as having Galactic colours and are plotted as unfilled, dark red stars. In the same plot we also mark sources classified as cataclysmic variable (CV) stars in SIMBAD (unfilled black squares). It can be seen that many stars which lie in the extragalactic colours region are in fact CVs, where the X-ray emission may arise from the accretion process onto the white dwarf.

In summary, to classify the hard-band selected sources with optical counterparts, we first remove 220 sources where one or both colours could not be computed, mostly due to issues with the W1 photometry, especially in the SEP region, or where sources do not have a sufficient signal-to-noise ratio in these photometric bands. Applying the colour cuts leaves 96 sources which are classified as likely extragalactic, and 23 classified as likely Galactic. Using all classification methods 2340 sources are classified as likely extragalactic or extragalactic, and 362 are classified as likely Galactic or Galactic. Out of the 2547 sources with good p_any, 2114 are classified as likely extragalactic or extragalactic, and 337 are classified as likely Galactic or Galactic, indicating that ~80% of the sample is extragalactic.

We note that the classifications based only on colour-colour classifications should be interpreted with some caution, particularly for the stars, as some are located in a region of the parameter space (upper-left quadrant of Fig. 12) which is occupied by extended (and thus likely extragalactic) sources with Galactic-source-like colours. Furthermore, we again stress that sources with low p_any may have different astrophysical origins for the X-ray and W1 photons, making the W1-X-ray colour unreliable.

Finally, the bottom right panel of Fig. 12 shows the W1 − W2 colour versus the W2 magnitude for these sources. Overplotted here are tracks corresponding to the colours of typical sources as they increase in redshift, akin to those presented in Salvato et al. (2022). A majority of extragalactic sources are shown to lie in the vicinity of the QSO and NGC 4151 tracks, with very few galactic sources matching Elliptical and SB tracks. Also of interest is a smaller number of sources which appear to lie along the

Seyfert 2 track, which are commonly associated with obscured AGN. These sources are discussed further in Sect. 3.7.

|

Fig. 12 Colour-colour classification plots adapted from Salvato et al. (2022). Only sources with type PSF in LS10 and sources where the signal-to-noise ratio >3 in all photometry bands are plotted. Sources classified as extragalactic (spec-z>0.002) are shown as filled purple diamonds, sources classified as Galactic (significant parallax at >5σ or spec-z<0.002) are shown as filled red stars, sources classified as extragalatic based on their colours are plotted as unfilled dark purple diamonds, and sources classified as Galactic based on their colours are plotted as unfilled dark red stars. These shapes and colours are labelled in the bottom right panel. Cataclysmic variable stars are plotted as unfilled black squares in the bottom plots. The tracks on the bottom right show the evolution of the colour-magnitude space occupied by different sources, with increasing redshift from left to right. Redshift ticks can be found at z = 0.04, 0.2, 0.4, 0.92, and where available at z = 1.4, 3.8. |

3.6 Beamed AGN

Having defined a sample of secure and likely extragalactic sources, it is also of interest to identify which of these may be associated with blazars. The X-ray emission from these sources is likely to originate in the jet rather than in the X-ray corona, and may be relativistically boosted. This means that the total spectral shape and luminosity is unlikely to be representative of the corona, so removing these from an AGN sample will improve our understanding of the true coronal emission.

To identify candidate beamed AGN in our sample, we perform a cross-match with three catalogues/databases; CRATES, BZCAT and SIMBAD. Further investigation of all blazars in eRASS1, including a more detailed analysis of source types and X-ray spectral properties, will be presented in Haemmerich et al. (in prep.); here we apply a simplistic approach to remove known beamed sources. CRATES (Healey et al. 2007) is an 8.4GHz selected flat-spectrum radio quasar (FSRQ) catalogue constructed using multiple radio surveys and additional followup work to achieve nearly uniform sky coverage of latitudes |b| > 10°. The Roma-BZCAT catalogue is a multi-frequency blazar catalogue, containing both FSRQ sources and BL Lac. The 5th edition was used here (Massaro et al. 2014), containing 3561 sources, all of which have radio detections. Finally, to identify other blazar candidates, we cross-match with SIMBAD. Sources which have a type of Blazar, BLLac, Blazar_Candidate, or BLLac_Candidate are flagged. The information is stored in the column class_beamed, where sources which appear in BZCAT have a class of 1, sources appearing in CRATES have a class 2, sources in SIMBAD have a class 3, and other sources have class 0. In total, 319 sources are flagged as beamed. These sources are thus removed from the AGN sample, and will be presented in Haemmerich et al. (in prep.).

3.7 Multi-wavelength properties of the hard-only sources

Of particular interest throughout this work is the hard-only sample, which is likely to consist largely of obscured AGN which lack soft X-ray emission. However, it should also be noted that the hard-only sources may have properties which are not consistent with the remainder of the main sample. In particular, it is clear that many more hard-only sources are in fact spurious, and that even some sources which have a good counterpart may still be chance associations of galaxies and spurious hard X-ray detections.

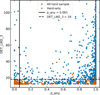

One visualisation of this can be seen in Fig. 13, which shows the distribution of de-reddened r magnitude (corrected only for Galactic absorption) and hard X-ray fluxes for the sample. The population of stars is evident, with R < 12.5 for typical X-ray fluxes. A very large population of hard-only sources lie in an extreme region of the parameter space, with relatively typical hard X-ray fluxes but extremely faint r band magnitudes. However, it can also be seen that many of these sources have low p_any. To further investigate this, we also plot a second subsample with a 99% purity cut on p_any, corresponding to p_any > 0.61, shown in dark red. Here it is clear that while some hard-only sources are fainter in r, other sources with R > 22 are likely wrong associations. This seem particularly relevant for the hard-only sources, where 24 sources or ~20% of the sample lies in the region of R > 22 and log(ML_FLUX_3) ~ −12.25. Given the high expected X-ray spurious fraction (~70%) of the hard-only sources, which is understood using simulations (see Fig. 2), this 20% spurious fraction is not surprising. We do not make further cuts on this sample in order to void further reducing the completeness, however a purer sample could be obtained by making further cuts on DET_LIKE_3, p_any, or in optical magnitude (e.g. R > 22). Further investigation optical and X-ray flux ratios of these sources is left for future work, and combining data from future eROSITA all-sky surveys will help reduce the fraction of spurious X-ray sources.

Also of interest is to examine the location of the hard-only sources in the W1 − W2 versus W2 plane, and in particular in reference to the Seyfert 2 track. This is shown in Fig. 14. We note that this figure includes sources which have extended PSF types, and so includes additional source as compared to the bottom right panel of Fig. 12. Many hard-only sources are consistent with being Seyfert 2 AGN. Some are also consistent with stellar populations, and additional sources are also in agreement with being very bright QSOs, which is worthy of further exploration.

Additionally, the optical light profiles of sources which do not have an optical type of PSF are fitted in order to measure the ellipticity of the source (Dey et al. 2019). For sources where this information is available, the ratio between the semi-major and semi-minor axes, a/b, is shown in Fig. 15. Hard-only sources are shown separately, and are binned up in order to better compare the distribution of sources to the rest of the hard sample. The median b/a for the sources with both hard and soft detections is 0.71, whereas for hard-only sources, it is 0.52. This could imply that the hard-only sources tend to preferentially found in galaxies which are edge-on. This interpretation is discussed further in Sects. 8.2 and 9.2

|

Fig. 13 De-reddened r magnitudes and hard X-ray (2.3–5 keV) fluxes for the hard sample. All hard sources with p_any less than the threshold of 0.033 are shown as blue unfilled circles, and sources with good p_any are shown as blue filled circles. Hard-only sources with p_any less than the threshold of 0.061 are shown as orange unfilled squares, and hard-only sources with good p_any are shown as orange filled squares. A 99% purity cut on p_any at 0.61 is also applied, and these sources are shown as dark red filled squares. |

4 Counterparts outside the legacy survey footprint

As an additional complement to the LS10 counterparts, it is also of interest to attempt to identify counterparts outside of the legacy survey area. A comprehensive treatment like for LS10 with other surveys goes beyond the scope of this work. However, for the hard-detected sources which also have soft emission, the positional uncertainties are very small (cf. Fig. 3). This enables a simple positional match to archival catalogues. These sources are primarily located at low Galactic latitudes which are not covered in LS10, meaning that this sample consists primarily of stars and AGN located behind the Galactic plane. These AGN are of particular interest as it is more difficult to select AGN here. To do so, we first select 1710 sources which are outside of the LS10 MOC, have no flags, and are not hard-only. We then perform a 5” positional match to public QSO catalogues; the Gaia/Quaia AGN sample (Storey-Fisher et al. 2023), the Gaia/unWISE catalogue (Shu et al. 2019) and the Million Quasar Catalog (MilliQSO; Flesch 2023). Although we expect some of these X-ray sources to be stars, given the extremely low positional errors on the X-ray positions, we can still consider matches between X-ray positions and known AGN as interesting AGN candidates which can be explored more in future eROSITA all-sky surveys. In all, we recover 692 matches out of 1710 sources, such that 40% of the sample outside LS10 has an QSO match. Out of these, 339 have spec-z from Quaia, and 349 have photo-z from the other catalogues (Flesch 2023; Storey-Fisher et al. 2023). More details of this procedure are described in the appendix, and these sources are also shown in Fig. 19.

|

Fig. 14 W1-W2 and W2 magnitudes shown for the eRASS1 hard sample. All hard sources with p_any less than the threshold of 0.033 are shown as blue unfilled circles, and sources with good p_any are as with blue filled circles. Hard-only sources with p_any less than the threshold of 0.061 are shown as orange unfilled squares, and hard-only sources with good p_any are shown as orange filled squares. Tracks as in Salvato et al. (2022) and Fig. 12 of this work are shown in various line styles and colours. Redshift ticks can be found at z = 0.04, 0.2, 0.4, 0.92, and where available at z = 1.4, 3.8. |

|

Fig. 15 Ratio of the semi-major to semi-minor axes of the optical counterparts, where available. Sources are shown as blue solid lines, and sources in the hard-only sample are shown as orange dashed lines. The respective median values are indicated with vertical lines. Only sources with good p_any are shown. |

5 Comparison with Swift BAT AGN

5.1 Match to Swift BAT

The Swift Burst Array Telescope (BAT) is sensitive in the 15–150 keV energy range, and is thus highly complementary to many other contemporary X-ray missions. With a large field of view and rapid slew capability, the mission was designed to provide rapid follow-up for Gamma-ray bursts and other highly energetic events. The BAT instrument has also surveyed the sky in X-rays, with the first 105 months of operation providing a sample of 1632 hard X-ray detections (Oh et al. 2018) with a sensitivity of 8.40 × 10−12 ergs s−1 cm−2 in the 14–195 keV band, over 90% of the sky. Counterparts have also been identified for these sources in Oh et al. (2018) and Ricci et al. (2017), and sources are classified based on their optical spectra or using other multi-wavelength properties. This sample is of interest for comparison with eROSITA, as they are in highly complementary energy ranges, and both surveys cover bright, nearby sources, especially AGN.

To find matches with BAT, we first perform a 60 arcsecond cross-match between the eROSITA sky positions and the Swift BAT 105 month catalogue counterpart positions provided by Oh et al. (2018). By examining the distribution of separations, we determined that a 10 arcsecond match radius was appropriate. It should be noted here that while matching the X-ray positions directly to an optical catalogue is not appropriate in this sample, it is extremely unlikely to have a spatially coincident BAT and hard X-ray selected eROSITA source which do not have the same physical origin, justifying this matching procedure. This can also be justified using a geometrical argument: if we draw 30 arcsecond circles around each eROSITA source, we cover only 0.0014% of the sky. Multiplied by 849 BAT sources (which should have no positional error, since we use the optical counterparts), this is only about a 1% chance that all the sources would be found in this small sky area, which is highly implausible. Out of the 849 BAT sources in the eROSITA-DE area, we found 487 matches, of which 481 are point sources and 456 are point sources with no eROSITA flags. There are no duplicates in this matching analysis. Additionally, 250 matched sources were inside the LS10 area. For the subsequent analysis, we consider all 487 matches for comparison.

It is then of interest to determine which types of BAT sources are detected by eROSITA. BAT sources are assigned a type by searching for publicly available optical soft X-ray and spectra, and the procedure is described in Oh et al. (2018). Figure 16 (top) shows the numbers of matched and non-matched sources in the eROSITA-DE sky, separated by the different source classes in the BAT 105 month catalogue (cf. Table 1 of Oh et al. 2018). A large fraction of the sources detected with eROSITA are Seyfert 1 AGN with broad optical lines (142), followed by Seyfert 2 AGN (126) and beamed AGN (52). A large fraction of CVs, X-ray binaries, and unknown AGN (where the optical spectra and type are not available/known) are also detected, as well as sources of Unknown class II, which are sources with previous soft X-ray detection, but with unknown type. Of the 15 matches with the hard-only sample, seven are Seyfert 2, two are AGN of unknown class, two are unknown class II sources, and four are X-ray binaries.

Beyond type 1 and 2 Seyfert galaxies, examining the optical spectra can also allow further subdivision into the classes Seyfert 1, 1. 2, 1.5, 1.8, 1.9, and 2.0, classified based on the strength of the broad optical lines. These are also taken directly from the BAT 105 month catalogue (Oh et al. 2018). Figure 16 (bottom) shows the numbers of matched and non-matched sources in the eROSITA-DE sky, according to these optical classes. It is clear that eROSITA is highly sensitive to detecting the relatively un-obscured, type 1–1.9 AGN, but is much less sensitive to detecting type 2 AGN, which is sensible as these sources are likely to be heavily obscured and thus very dim or absent in the eROSITA bandpass. The seven hard-only Seyfert 2s and two hard-only unknown AGN are also shown.

An earlier release of the BAT catalogue (the BAT 70 month catalogue) also reported information on the soft X-ray properties, including the column density, of BAT-detected AGN, where available (Ricci et al. 2017). We therefore match the eROSITA hard sample to this catalogue, finding 273 matches out of 435 sources in the eROSITA-DE sky. This match can also be justified by assuming that spatial coincidence of an eROSITA hard source with a Swift BAT source is extremely unlikely. For sources where the soft X-ray follow-up detection (e.g. with Swift XRT, Chandra, XMM-Newton) allows for the constraint of the column density (293 sources), we also identify matched sources in eROSITA (159). The histogram of these column densities is shown in Fig. 17. This is not representative of the true underlying column density of AGN in the local Universe, as many sources did not have significant data quality to constrain the column density and have subsequently been removed from this plot. Some of these sources may have very low column densities which required more sensitive soft X-ray data to be well constrained, as evidenced by the fact that 114/142 sources with unconstrained column densities were eROSITA detected.

The analysis shows that eROSITA appears to reliably detect sources up to column densities of 1023 cm−2, where the detection fraction appears to decrease to ~50%. At higher column densities above 1023 cm−2, the detection fraction decreases to 10–20%. Since the BAT instrument is relatively unbiased to obscuration, we can consider that these fractions represent the completeness of the eROSITA samples with respect to the absorption column density. In the Compton thick regime, we find one matched source; however, this is the Circinus galaxy, the redshift of z = 0.0015 is so low that we may be detecting starburst emission with eROSITA (see e.g. Arévalo et al. 2014; Bauer et al. 2015) rather than directly detecting the transmitted component of the AGN. Of key interest as well is the distribution of the seven hard-only sources which also appear in this catalogue. All seven have column densities of >1022.5 cm−2, and a majority (4/7) are above 1023 cm−2, further demonstrating that eROSITA can detect and select obscured AGN. Subsequent eROSITA all-sky surveys will permit a further investigation of these sources, including identifying more sources and performing more detailed X-ray spectral analysis.

The distribution also shows a bimodality in column densities with a dip at ~1022 cm−2, which is also visible in the eROSITA matched sources and is also found in eFEDS (Nandra et al. 2025). This suggests the hard X-ray selected eROSITA sample will be able to give further constraints of column densities of AGN in the local Universe.

|

Fig. 16 Comparison to the BAT sample. Top: distribution of BAT 105 month catalogue sources in the eROSITA-DE sky according to type (black), and of matched eROSITA sources according to BAT type (blue). Bottom: distribution of BAT 105 month catalogue sources according to BAT class (black), and of matched eROSITA sources according to BAT class (blue). Hard-only eROSITA sources are shown in orange. |

|

Fig. 17 Distribution of column densities log(NH) of sources with soft X-ray detections in the BAT 70 month catalogue, shown for sources in the eROSITA-DE sky (black) and for those matched with eROSITA sources (blue). Hard-only eROSITA sources are shown in orange. |

Sample of Piccinotti AGN in the eROSITA-DE sky.

5.2 Comparison to the LS10 positions

In order to assess the validity of the LS10 counterparts, an independent check is to compare the positions to those derived from the BAT counterpart positions. To do so, we select the 250 sources which had BAT 105 month catalogue matches which are in the LS10 area, and remove three sources which were flagged as problematic in the X-ray catalogue. We remove one additional source, NGC 1365, which has missing photometry in the LS10 catalogue and is thus not found as a counterpart. We then match these to the X-ray sources, and measure the separation between the BAT counterpart positions and the LS10 counterpart positions. Of these 246 sources, 227 have separations of less than two arcseconds, and are thus determined to be associated with the same optical source. For the remaining 19 sources, we visually inspect the LS10 image, and verify each source in SIMBAD. The maximum separation is ~8 arcseconds. All sources appear to be consistent, and every difference in position seems to be related to small differences between the coordinates in the BAT catalogue versus other catalogues. This could be a rounding or entry issue in the catalogue. Crucially however, the analysis lends additional faith to the NWAY counterparts, and suggests that the training sample from Salvato et al. (in prep.) is sufficient for use in this work. More discussion are given in Sect. 8.1.

6 Comparison with the Piccinotti AGN sample

The HEAO 1 experiment A2 (Rothschild et al. 1979) performed an X-ray survey in the 2–10 keV band, covering 8.2sr of the sky at galactic latitudes |b| > 20° with a limiting sensitivity of 3.1 × 10−11 ergs s−1 cm−2. A total of 85 sources were detected and identified, 31 of which are AGN, forming a complete hard X-ray selected sample consisting of 27 Seyfert 1s, three Seyfert 2s, and one blazar (3C 273) (Piccinotti et al. 1982). These well-studied AGN are worthy of analysis with eROSITA, as this may be considered as the previous best, all-sky, hard (2–10 keV) selected sample of AGN.

Out of the 31 AGN in the Piccinotti sample, 20 are found in the eROSITA-DE sky. All of these sources are detected by eROSITA (both in the main and hard sample) and can be found in Table 3. eROSITA-derived 2.3–5 keV fluxes and 2–10 keV Swift BAT follow-up fluxes are given for each source, as well as the fluxes derived in HEA0-1. It can immediately be seen that many of the eRASS1 and BAT fluxes are below the values measured in HEAO1, and indeed many are below the HEA01 limiting flux. This may be due to intrinsic variability, as HEAO1 detected only the brightest sources in the X-ray sky and likely detected only AGN in a bright state. The relative fluxes measured between missions are also model depedent, and may be in better agreement with improved spectral modelling.

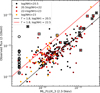

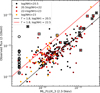

The Swift BAT and eRASS1 fluxes are plotted in Fig. 18 for Piccinotti AGN (black, open squares), as well as the other sources in the BAT 70 month sample (circles), with colours indicating the different measured absorption column densities. The 70 month catalogue is used in order to obtain the soft X-ray fluxes released in Ricci et al. (2017). Open circles show the sources with non-detections in eROSITA which have measured column densities of NH<1022.5 cm−2, and the eROSITA fluxes are plotted at the 90% flux limit of eRASS1. Sources which are more obscured but not detected in eRASS1 are not shown, since it is understood that these sources were likely not detected due to obscuration and the relatively lower sensitivity of eROSITA in the hard band. In order to compare the fluxes measured by different instruments and in different energy bands, we trace two solid lines; the black line shows the equivalent 1-to-1 line assuming a photon index of Γ = 1.8 and a column density of 1020.5 cm−2, which are the approximately average parameters of the matched eROSITA and BAT sample. While this tends to pass through the approximate parameter space occupied by most sources, a number lie significantly above or below this line.

Noticing that many of the sources which lie above the line show evidence for significant absorption, we add the second, red line which shows the equivalent 1-to-1 line assuming a photon index of Γ = 1.8 and a column density of 1022.5 cm−2. Many sources with higher column densities lie closer to this line; while most still lie below it, the line indicates a very simple scenario with a fixed photon index of 1.8, and does not account for other effects including changing photon indices, a more complex spectral shape, or errors on the measured fluxes, and so should only be considered a rough indication of the parameter space. This analysis demonstrates that fluxes measured between Swift and eROSITA are moderately in agreement, and does not reveal strong evidence for heavy pile-up in the hard X-ray detections of eROSITA.

|

Fig. 18 eROSITA 2.3–5 keV fluxes (ML_FLUX_3) and BASS fluxes (2–10 keV) for Piccinotti AGN (black open squares), as well as the other sources in the BAT 70 month sample (circles). Open circles show the sources with non-detections in eROSITA that have measured column densities of NH<1022.5 cm−2. The black solid line shows the equivalent 1-to-1 line assuming a photon index of Γ = 1.8 and a column density of 1020.5 cm−2. The red solid line shows the equivalent 1-to-1 line assuming a photon index of Γ = 1.8 and a column density of 1022.5 cm−2. Black filled circles indicate sources with a measured column density of <1020.5 cm−2, dark red filled circles indicate sources with a measured column densities of 1020.5–22.5 cm−2, red filled circles indicate sources with a measured column density of 1022.5–23 cm−2, and orange filled circles indicate sources with a measured column density of >1023 cm−2. |

7 Variable point sources

Boller et al. (2025) has analysed a sample of sources from the eRASS1 main catalogue to check for evidence of variability within eRASS1. Due to the scanning pattern of eROSITA, this serves as a test of variability on 4-hour timescales, where 4 hours is the length of one eroday, which is the length of one revolution of SRGin all-sky survey mode. For each source, a light curve was produced (Merloni et al. 2024). Two variability tests are then performed: the maximum amplitude variability, defined as the span between the maximum and minimum values of the count rate, and the normalised excess variance (NEV), defined as the difference between the observed variance and the expected variance based on the errors (see Boller et al. 2022, 2025). These variability tests are run in the 0.2–2.3 keV band, so while they do not overlap with our hard sample selection, they still provide an interesting look into the variability in the energy band where eROSITA is most sensitive. Variability in the hard X-ray is more difficult to disentangle from other events, including background flaring, pile-up and protons striking the detector.

Matching the variable source catalogue with the hard-band catalogue, we find that 326 sources show evidence for variability. Out of these, 159 sources are within the LS10 area, and have good p_any, suggesting these are secure counterparts. Of these 159, 40 sources have spectroscopic redshifts of z > 0.002 and are thus confirmed to be extragalactic, and 109 are stars. Outside of the LS10 area, 125 sources have AGN matches (see the appendix), five of which have a spectroscopic redshift of z > 0.002 from Quaia. This gives a total of 45 variable AGN with a spec-z. These AGN are of particular interest for future followups within later eRASSs or with other missions, to study both the short- and long-term variability of spectroscopic AGN. The low number of sources which are highly variable on short timescales also supports creating X-ray spectra from the full eRASS, rather than dividing by eroday. Such spectra are investigated further in Sect. 8.2. Further details of the specific variability properties of these sources and a more detailed study of their variability is left for future work.

8 A hard X-ray spectroscopic sample of AGN

8.1 AGN sample designation

A key output of this classification work is a pure, hard X-ray selected sample of AGN detected with eROSITA. To ensure a very pure sample, we select only sources with reliable counterparts, and only those with spectroscopic redshifts, where z > 0.002. More concretely, this sample is assembled from:

All LS10 sources with a good counterpart and a spectroscopic redshift z > 0.002, and removing sources with class_beamed > 0 (1243 sources, 23 hard-only).

Three AGN which were in the LS10 area but were missing counterparts, as listed in Table 2 (three sources, zero hard-only).

Sources from the Swift BAT 105 month catalogue cross-match which satisfy the following criteria: eROSITA position outside of the LS10 area, no flags in the X-ray catalogue, X-ray point source, BAT 105 month catalogue Class of 40, 50, or 60 (corresponding to Seyfert 1, Seyfert 2, or LINER AGN, excluding beamed AGN and unknown type AGN) (82 sources, six hard-only).

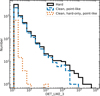

In total, this selects 1328 sources, of which 29 are hard-only, as can be seen in Table 1. The luminosity-redshift distribution of these sources is shown in Fig. 19, with a median redshift of z~0.19. Sources detected in the BAT 70 month sample are also shown in pink, and sources detected in the eFEDS hard sample are indicated with green triangles. This sample is ideal for spectral analysis, since, as demonstrated by Waddell et al. (2024), the presence of the photons above 2 keV will allow for excellent modelling of the contribution from the hot X-ray corona, as well as an investigation into soft X-ray emission and absorption. Furthermore, the eROSITA sample, in addition to being all-sky, is able to probe dimmer sources than the previous all-sky hard X-ray selected sample (HEAO-1, flux limit shown with the dashed black line) and than the BAT all-sky survey, and is also capable of finding many more sources at higher redshifts. The sample covers a broad redshift range of 0.003–3, and an even broader hard X-ray luminosity range (estimated from the 2.3–5 keV band counts) of 1041–1047 ergs s−1. We caution that while only few eRASS1 sources appear above the HEAO1 flux limit, all 20 Piccinotti AGN in eROSITA-DE are still detected, albeit at lower flux states.

Also shown here are the 339 sources with spectroscopic redshifts obtained from matching the sources outside the LS10 area to AGN catalogue, as described in Sect. 4 and the appendix. These sources lie primarily within the Galactic plane and may be obscured by the local gas and dust, which may decrease the luminosities for these sources. A majority are also found at higher redshift, although examining the histogram in Fig. 11, we can see that the Quaia redshifts from the area in LS10 are similarly higher, so this may be due to the sensitivity and bandpass of the spectrograph on board Gaia. It should also be noted here that some of the higher-redshift sources may be blazars, and should be treated with caution.

|

Fig. 19 Hard X-ray luminosity vs redshift for various hard X-ray selected samples. eRASS1 AGN are shown as blue circles, eRASS1 hard-only AGN are shown as orange squares, Swift BAT AGN from the 70 month catalogue are shown as pink x, and the eFEDS hard sample are shown as green triangles. The flux limit of HEAO-1 is shown as a black dashed line. Sources outside LS10 with spec-z are shown as black crosses. |

8.2 X-ray spectral analysis

Detailed X-ray spectral fitting of the entire spectroscopic redshift sample of 1328 sources is left for future work. Here we focus on the hard-only sources, of which 29 are not beamed and have spectroscopic redshifts z > 0.002, 23 obtained from the NWAY LS10 match and six from the Swift BAT match. This interesting subsample covers a large range in redshift 0.003 < z < 1.5 and hard X-ray luminosity 1041–1046 ergs s−1, and are likely to be heavily obscured AGN. We fit each eROSITA X-ray spectrum in the 0.3–8 keV range with a torus model (UXClumpy; Buchner et al. 2019), using BXA (Bayesian X-ray Analysis; Buchner et al. 2014). BXA uses nested sampling combined with XSPEC (v. 12.12.1; Arnaud 1996) in order to explore the full model parameter space to best estimate parameters and enable model comparison. The model UXClumpy includes transmitted and reflected components with fluorescent lines obtained by assuming a clumpy torus with a specified opening angle and inclination. Since many of the eRASS1 spectra have very few counts, some model parameters are frozen to reasonable values obtained from Buchner et al. (2019), including the width of the Gaussian distribution modelling the vertical extent of the torus cloud population (TORsigma, 20), and the viewing angle of the torus (Theta_inc, 45°). The photon index is given a Gaussian prior centered on 1.95 with a width of 0.15, and the column density varies uniformly between 20 and 26.

In order to model an additional soft population of X-ray photons, an additional power law is added, with photon index and normalisation linked to the UXClumpy component. This scattered power law is then renormalised by a constant factor which is left free to vary between 0.01 and 0.1. There are a number of interpretations for this soft X-ray emission; likely it represents a population of scattered photons which leak through the torus and pass into our line of sight (Brightman & Nandra 2011; Liu & Li 2014; Furui et al. 2016; Buchner et al. 2019), but soft X-ray emission can also be produced by other mechanisms such as supernova remnants, ultraluminous X-ray sources, and X-ray binaries (see e.g. discussion on Circinus in Buchner et al. 2019) within the host galaxy, which is unresolved in X-rays. An example of the corner plot for source 1eRASS J151012.0-021454 (LEDA 54130) is shown in Fig. 20. While some sources have double peaked solutions for the column density, others, as this one, are well-constrained, with little degeneracy between parameters.

The resulting column density distribution is shown in Fig. 21. The eRASS1 hard-only sources are shown in orange. A comparison is also given to the eFEDS sample, using spectral modelling as described in Nandra et al. (2025). The eFEDS hard sample is shown with a green dash-dotted line, and the eFEDS hard-only sources are shown in black. While the hard sample as a whole contains many very bright, unobscured AGN, the hard-only sources recover a population of moderately obscured AGN, with column densities of ~1023–24 cm−2. These column densities are higher than what is often found in the discs of galaxies, so may originate in more obscured material closer to the central engine.